2013 G. Wesley Johnson Award: How public history matters for undergraduates

17 April 2013 – Elizabeth Belanger

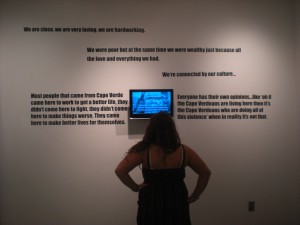

Oral History quotes and a video of historic images were juxtaposed with negative press clippings in the “I’m Not Who You Think I Am” section of the 2010 exhibit which examined questions of identity and perception within the Cape Verdean community. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Editors’ Note: This series showcases the winners of the National Council on Public History’s annual awards for the best new work in the field. Today’s post is by Elizabeth Belanger, author of “Public History and Liberal Learning: Making the Case for the Undergraduate Practicum Experience,” which won the 2013 G. Wesley Johnson Award for the best article published in The Public Historian in the previous calendar year.

In the winter of 2011, American Historical Association President Anthony Grafton declared that “history is under attack.”[1] In the year leading up to his presidential address, history institutions like the National Archives and Records Administration, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Institute of Museum and Library Services had seen their funding reduced. In academia, history faculty members bowed under the increasing weight of a national assessment movement that required them demonstrate student learning outcomes in the major. Across the board, in academia and outside, critics challenged the usefulness or even purpose of professional historians.

Those of us in public history would like to think that we are not intended targets of many of those criticisms. Our graduates are not groomed only for the academy, but rather educated to work in a number of career fields including archives, historic resource management, K-12 education, and museums, to name a few. We don’t expect that our scholars will be sequestered in ivory towers, but rather will work directly with members of the public, engaging them in important investigations of our past. But those expectations for those in the world of undergraduate public history may not be borne out as we would hope. My experiences with undergraduates suggest that only a few of the undergraduates who take public history courses go on to get advanced degrees in the discipline. For some of these students, the public history curriculum might consist of a single elective course, “Introduction to Public History,” which counts for their history major. Larger colleges and universities might have a public history track within the history major, but only a small percentage offer degrees in public history. If only a few of our students who take a public history class go on to work in the field, how do we justify public history in undergraduate programs?

The “Feliz Anniversario: Happy Birthday” section of the 2010 exhibit explored how cultures and traditions change to incorporate both the past and present, the older and younger generations, and the old world and the new by recreating of the sights and sounds of a birthday celebration. Quotes taken from oral histories and photographs from community members addressed themes including food, music, language, and cultural assimilation. Photograph courtesy of the author.

The genesis of my article can be traced back to a belief in the power of public history to transform student learning. It’s a belief that is deeply rooted in my own educational experiences, experiences that mirror those of my students. I didn’t major in history as an undergraduate. I actually never took a public history course because my small liberal arts college didn’t offer one. However, throughout my undergraduate and later graduate years, I found myself drawn to projects that connected the past to the present and courses, internships, and jobs that allowed me to serve communities. These courses didn’t just teach me how to conduct an oral history interview or research local history; they profoundly transformed how I viewed myself as a citizen and my role in my community. As a scholar, I found an academic home in public history, at a small liberal arts college much like the one I attended. It was within that setting and amidst a growing national debate about the value of history that my public history practicum emerged.

Public history projects take their shape, in part, from the setting in which they emerge. As a practitioner and a scholar, I have been amazed at the innovative and compelling student projects that are highlighted in the NCPH student awards and at the annual meetings. But as I listened to the panels and read the award notices over the past few years, I couldn’t help but feel a disconnect. Many of those projects were sponsored by large institutions, funded by national grants and utilized the talents of teams of faculty, graduate students, community leaders and consultants. As I set out to craft a public history practicum course for undergraduates at a small liberal arts school, I found myself wading into a pool of uncharted depth. Knowing that my students didn’t have the time, training or resources to produce something that mirrored the work of their graduate student counterparts at larger universities, I set out to document the value of the process.

My article, “Public History and Liberal Learning: Making the Case for the Undergraduate Practicum” (The Public Historian Vol. 34 No. 4) documents what my undergraduate students gained from their public history course. In doing so, it encourages broader consideration of what public history can offer to undergraduate students. It is based on a case study of a two- year public history/public art project that partnered sophomore undergraduates at Stonehill College with a local non-profit social service agency. Looking beyond graduate training, jobs and even learning outcomes within the history major, the article highlights the ways in which public historians, in the words of former NCPH President Marianne Babal, are “bridge builders.”[2] It argues that the most valuable tools we can impart to our students are the tools that emerge from our practices of civic engagement and collaboration. Those student learning outcomes are documented not by the end projects, an exhibit and neighborhood park revitalization, but rather through a careful study of students’ reflections about the process.

Local youth painting bricks for the community garden in the 2011 park festival. Photograph courtesy of Stonehill College.

As the public history community continues to advocate for the importance of history to public life, I encourage us not to forget the voices of our undergraduate students. Indeed, if we are living in a time when history is under attack, surely one of our best defenses is a generation of students who have experienced, as one of my students put it, how history “can be a catalyst for community building.” As we think ahead to next year’s classes, exhibits, projects and reports, consider as well the ways in which we can provide our students, interns, and partners the structure and time to do what comes so naturally to us: reflect on the process of “doing” public history and the many lessons it teaches us.

~ Elizabeth Belanger is Assistant Professor of History and Director of the American Studies Program at Stonehill College.

[1] Anthony Grafton “History Under Attack” Perspectives on History (January 2011): 3.

[2] Marianne Babal, “Sticky History: Connecting Historians with the Public: National Council on Public History Presidential Address” The Public Historian Vol. 32 No.4 (November 2010): 76-84.

this is the widest dream

Really useful information. I recently had to fill out a form and spent an enormous amount of time trying to find an appropriate Filling out forms is super easy with PDFfiller. Try it on your own here http://goo.gl/goMsCN MO 300-0739 and you’ll make sure how it’s simple.