A new way to be with one another

26 June 2018 – Kimber Heinz

incarceration, advocacy, social justice, community history, NCPH 2018 Awards, memory, sense of place, collaboration, politics, race, conference

Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of pieces by recipients of NCPH’s 2018 best in public history awards.

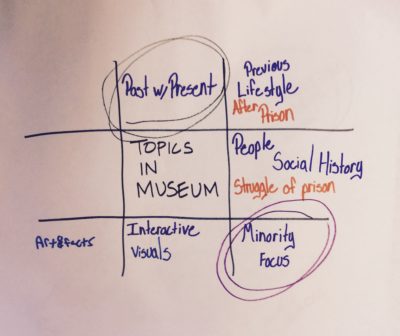

“Lotus Blossom” activity from a workshop with GrowingChange youth leaders about the mission of the prison history project. Photo credit: Kimber Heinz.

From this year’s annual conference, one thing seems clear: as public historians, we want our work to make a difference. Not just on a personal level, but on a community, and even national, level. This was the first conference planned from start to finish after the 2016 election. Its theme was “Powerlines,” and I was honored to attend as a recipient of an NCPH New Professional award.

Like many others following Trump’s election, the flood of fear-based, extractive policies and executive orders, along with the increasing visibility of white supremacist violence, have spurred me to action. I find myself asking, “What can I do to stop this? Is being a social justice-minded public historian enough? How can my history work concretely support progressive social change?”

One of the books that most moved me in 2017 was Hegemony How-To by Jonathan Matthew Smucker. Sociological theory meets community organizers’ manual, it speaks to the need for progressives to recruit like we mean it. It speaks to how framing our work as “activism”—rather than the things we stand for (e.g. democracy, sanctuary, justice, freedom)—keeps us small. Though not the first person to do so, Smucker points to the articulation of a new, collective “we” as an expression of grassroots power. People in power often speak for “us” as Americans, but what if “we,” the people who live here, spoke for ourselves, together?

This book made me think of the the potential of public history to support social change. As a former full-time community organizer, what got me interested in public history was my assessment of its capacity for transformation; history provides an opportunity for connection with others, across differences, about what it means to be human.

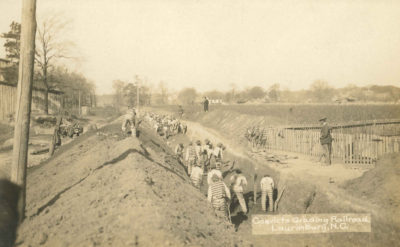

Postcard of prisoners working on the railroad in Scotland County, NC, circa 1900. Photo credit: Thomas McKinnon.

In addition to Bull City 150, a local history project to contextualize the roots of present-day inequalities in Durham, North Carolina, I am working on a project based in Scotland County, North Carolina, a rural area with one of the highest unemployment rates in the state. It partners with a youth-led organization, GrowingChange, that is transforming a former chain gang prison into a farm and community center, to interpret the history of the site. This project, which has started out as a traveling exhibition, weaves together stories about the prison’s history from many different perspectives, from those of people who were incarcerated there, to those who grew up at the prison as children of chain-gang-era staff, to those of former prison guards and superintendents. (See History@Work’s coverage of the Guantanamo Public Memory Project for some similar perspectives.)

One thing that I have (re)learned while trying to create a compelling exhibit narrative, one that draws on many disparate historical voices and current-day opinions about the U.S. prison system, is that people are complicated. Most people’s stories do not fit neatly into boxes, or into catch-all categorizations of Right and Left. I have been surprised to find opposition to the dehumanization of mass incarceration coming from a former prison superintendent, and support for the prison system coming from some who have lost people to incarceration, because prisons provide jobs. As a self-identified leftist, it took me time to come to this realization, and to acknowledge these complexities.

As public historians, we have the opportunity to leverage the power of history to bring together people across differences to listen to each other’s stories. We can facilitate spaces where groups of people who do not know each other can be guided towards discussing major issues like mass incarceration through shared reference points, such as memories of a former prison in Wagram, North Carolina. We can support social change through striving to create public spaces where people can encounter each other in new, potentially transformative ways. Public history can be a vehicle for a new, collective “we.”

Of course, that doesn’t mean that everything is relative. White supremacy was the foundation of the southern prison system, a system that continues to disproportionately lock Black and Brown people in cages. How can material evidence of the white supremacist roots of prisons support a correct telling of what happened without shutting down dialogue? How can we use primary sources as evidence-based touchstones during difficult conversations? One of the terms that came up in many conference sessions in April was “non-negotiables,” which allow public history practitioners to articulate our political stance and name the limits of “shared authority.”

GrowingChange youth leaders grow food at a former chain-gang prison in Wagram, NC. Photo credit: GrowingChange.

Across political differences, many people in Scotland County support GrowingChange’s work to transform a historic site of confinement and torture into a place where people can thrive. GrowingChange’s youth leadership, a multiracial group of young men who have been directly impacted by the criminal justice system, are farming this site and transforming former prison cells into a community center and recreation area. Local supporters acknowledge the need for an alternative to mass incarceration and this as a way forward.

In addition to the direct benefit to the local community, what draws people, myself included, to support GrowingChange is its story, and the stories of the people connected to it. Board chair Noran Sanford often tells GrowingChange youth leaders, “You have to tell your story, otherwise someone might tell it for you, and get it wrong.” My public history partnership with GrowingChange aims to amplify those stories of local youth leaders, along with with those of the formerly incarcerated, and to invite the larger community to join the conversation about alternatives to mass incarceration. I hope that others will join, too, to help envision a new, collective “we,” a new way to be with one another.

~ Kimber Heinz is the exhibition project manager for Bull City 150 at Duke University in Durham, NC. She is also the museum coordinator for GrowingChange, a youth-led organization based in Scotland County, NC working to transform a former chain gang-era prison into a farm and community center. She is the former national organizing coordinator of the War Resisters League, based in New York, NY. She holds master’s degrees in Women’s and Gender Studies and Public History with a concentration in Museum Studies from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She lives in Mebane, NC.