A side or B side? Postindustrial artisans walking a fine line (Part I)

11 August 2014 – Cathy Stanton

Somerville’s Union Square has been relatively affordable within Boston’s expensive real estate market, but an impending city-led revitalization plan is already boosting prices in the neighborhood. Photo credit: Cathy Stanton

On a cold March evening this past winter, my students and I caught a bus from Davis Square, near Tufts University, to attend a public meeting in Union Square, at the other end of Somerville, Massachusetts. Within the generally-pricey Boston real estate market of the past two or three decades, Union Square has remained relatively affordable and as a result has been something of a haven for artists, artisans, low-income immigrants, and small, often marginal businesses. The March meeting, though, was part of an ongoing “revitalization” process that had already started to bring big changes to the square. Candidates vying for the role of “master developer” for the square were strutting their stuff, trying to demonstrate both familiarity with the neighborhood’s bohemian character and capacity to coordinate more than 2.3 million square feet of new development in seven blocks currently assessed at $26 million.

My class was conducting ethnographic research focusing on a collaborative of small artisanal businesses in a former industrial building in Union Square, and we were curious about how these kinds of companies–tied to currently-hip ideas about “maker culture” in some ways, linked with the longer history of small-scale local craft production in others–would appear within the image-making that was sure to be going on at the meeting.

“Fringe” is an interconnected mix of more than a dozen small enterprises that constitutes its own vibrant ecosystem within the changing economy of Somerville, Massachusetts. Photo credit: Cathy Stanton

The collaborative, fittingly called “Fringe,” came to our attention through Mimi Graney, executive director of the neighborhood redevelopment organization Union Square Main Streets. As Union Square has begun to become a desirable address again (in part through USMS’s efforts), Mimi has become a staunch defender of the kinds of often-unlovely spaces that suit the needs–and the budgets–of small-scale fabricators within a gentrifying area and a tech-driven economy. In a recent TEDx talk on the need to “keep the city gritty,” she made a case for resisting the usual push to fill empty mill buildings with housing. Instead, she argued that the challenge for her generation of urban redevelopers was to look at a space that was “humble, unassuming, maybe even decidedly unattractive, and not seek to transform it, but to put it back to work.”

In large part due to the spillover effect from nearby Cambridge, especially the high-tech hot-bed neighborhood around the Massachusetts Institute for Technology (MIT) and Kendall Square, Union Square has recently become home to a number of new-economy manufacturing ventures. These include a tech incubator (GreenTown Labs) and a large nonprofit makerspace (Artisans Asylum). Mimi mentioned these along with Fringe in her TEDx talk, but once we got talking with some of the key people at Fringe, we quickly realized that they saw themselves as being different both quantitatively and quantitatively from these other projects.

The distinctions they drew weren’t based so much on their particular mix of skills and products. Fringe’s blend of old and new crafts (think letterpress-printing next to video production, craft-beer-making alongside green roof design) is not unlike what’s going on in countless other co-working spaces around other cities at the moment. Rather, they distinguished themselves based on the scale and level of business operations they were trying to create and run. They weren’t looking toward multimillion-dollar initial public offerings (IPOs), the hope that tends to fuel high-tech start-ups. But unlike a lot of more avocational “makers,” they were aiming to make a steady living, and indeed all of the Fringe companies were operating in the black. The combination of being serious about running their businesses but also content to stay at a relatively modest scale was what made them unusual–and, in Mimi Graney’s view, valuable–in Union Square’s commercial ecology.

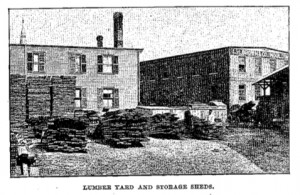

The modest industrial building was once used by a wood-working business. Photo credit: Somerville Journal, 1892

The Fringe collaborative’s unusual and precarious position was very much reflected in the space they occupied. The late nineteenth-century building originally housed a wood-working business that made cabinetry and moldings in an earlier era of rapid urban redevelopment and residential expansion around Boston. The IH Brown Company had lost its original location in Cambridge to a fire in 1886 and, like today’s artisans, found Union Square a more affordable alternative. The modest industrial building that they bought and expanded to suit their needs was never intended to be a showplace: it was tough, functional, and scaled to their busy but relatively small operation.

A late-twentieth century renovation by the current owner carved up some of the interior for individual artists and some storefront businesses, but most of the space remains open, adaptable, and fairly rough-edged. Those qualities–along with loading docks and other legacies of former industrial uses–helped Fringe’s member companies experiment with their own businesses as well as with the makeup of the collective itself. In their five years of existence, they had arrived at a very interconnected mix of small enterprises that constituted its own vibrant ecosystem within the changing economy of Union Square and Somerville.

Part 2 follows.

~ Cathy Stanton is a Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at Tufts University and Digital Media Editor for the National Council on Public History.

1 comment