Archives, technology, and the global outlook of public history

21 July 2016 – Vera Parham

Ruins of Ebla, a city in Syria, where one of the first archives of clay tablets was found, dating back to the third millennium BCE. Photo credit: Mappo

As most of us in the field of archival studies know, defining the archival profession is like trying to hit a moving target. The form and meaning of the profession have changed steadily and dramatically, as have the challenges and educational preparation. As technology has advanced the field, the work of archivists, as well as their training, has taken on a more technical turn. Yet while mastery of the new technology is very important, keeping a focus on the philosophical underpinning of archiving should not be overlooked.

There are many reasons archival education programs and the profession have become increasingly complex, such as the natural result of the introduction of technology, changes in how professionals identify themselves, and an increase in documents and collections. The growth of archives represents a fundamental shift in the economy. Paper archives were created thanks to the development of cheap production methods. The growth in paper prompted a need to find a way to preserve those artifacts in archives. As archivist Brien Brothman reminds us, by the time the Society of American Archivists was founded in 1936, this growth in documents and archives “was becoming unmanageable.”[1]

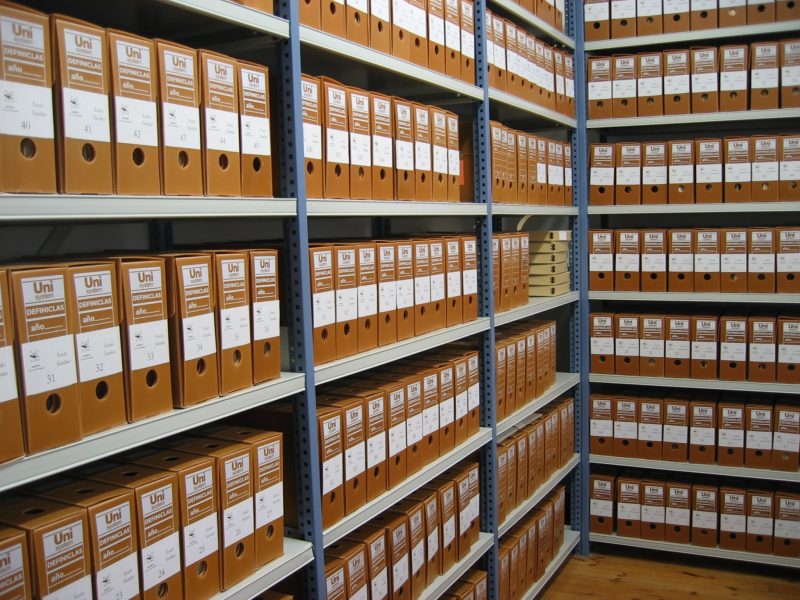

Shelves of archival materials. Photo credit: Archivo-FSP

Since 1936, our production of documentation has only increased. We create and consume and share more data than ever before, which means more and more archives and archivists. From 1936 to the present, though, the job description has remained the same: to house and protect items of historical significance and direct individuals to those items. The way we share and transmit those items may undergo revolution after revolution, but the fundamental use and purpose of this preservation will not. After all, we are simply finding new ways of creating useful documents. A document is not just a document, however, but is also a cultural artifact with multiple meanings in it. Cultures and nations use records to prove their past, their present and even their right to exist. So a lack of records, sloppy record keeping, or lack of access affects us much more than we can imagine!

New technologies have changed our access to information, as well as how we research and write. With the advent of computers and, even more importantly, the Internet, new worlds of access began to open up for both researchers and archivists. These new worlds represented both opportunities and challenges. Databases were created that could search through thousands and thousands of records in seconds. Digital catalogs could be created to provide information on collections. Eventually, digitization advanced to the point where documents could be scanned or photographed and stored, with associated metadata to enhance search capabilities.

Web banner for the Society of American Archivists’ 2014 annual meeting.

The challenges for the archivists grow in direct proportion to the development of technology. No longer is it enough to simply know how to appraise, arrange, and describe collections. They must also master the technology to make this information available to people around the globe.

Archivists control access to the preservation and dissemination of records–or the destruction of our collective past. This means that archivists need to have not only a firm moral compass, but a strong foundation in history and historiography. While not all archivists are historians, all archivists must have an understanding of history and the changing nature of artifacts, sources, documents and historical interpretation.

Our world today is expanding at a rapid rate. Technology allows us to know what is happening in the blink of an eye. History is a fluid process and our understanding of the past is individual and constantly changing. The study and function of archives illustrate these constant changes in perspective. That is why studying and understanding what we decide to protect as important, and what we decide to throw away, is key. A background in history will make for better decisions in accessioning collections. To accomplish this, we must advocate for more cross-disciplinary awareness and for archivists to have a strong background and training in history, not just the library sciences.

[1] Brien Brothman, “The Society of American Archivists at Seventy-Five: Contexts of Continuity and Crisis, A Personal Reflection,” The American Archivist 74, Fall/Winter (2011): 387-427.

~Vera Parham is an associate professor of public history at American Military University. Her work focuses on Native American history as well as the need for cultural awareness and sensitivity in archives and collections.