Cold War legacies: Preservation and use at historic sites

16 March 2018 – Billy Marino

Las Vegas Series 2018, preservation, community history, memory, sense of place, environment, sustainability, 2018 annual meeting

Nuclear bomb blast near Frenchman Flats, Nevada, 1957. Photo Credit: University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Special Collections, Manis Collection

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of pieces focused on Las Vegas and its regional identity which will be posted before and during the NCPH Annual Meeting in Las Vegas in April.

Cold War-era historic sites challenge public historians to strike a balance between the need for preservation and the need for continued use. How do we preserve the historical integrity of a place and still allow it to perform its purpose? Can that balance be found?

Apollo 8 liftoff. Photo credit: NASA History Office, Project Apollo

Archive

An intriguing example comes with the Launch Complex 39 at Kennedy Space Center (KSC), an area built for the Saturn V rockets that brought the Apollo astronauts to the Moon and was again used on February 6, 2018, to launch of Elon Musk’s SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket.[1] The whole of Launch Complex 39 is a testament to the massive innovation required to bring humans into space in the 1960s, and today is recognized as an important piece of American history. The Falcon Heavy’s launch mandated updates to the site, which removed the material culture by repurposing it for new uses. Yet, this launch is also making history, being the largest rocket to successfully leave Earth, boosted by a whopping twenty-seven engines and carrying a Tesla car complete with a dummy in a space suit blaring David Bowie’s “Starman” as it makes its way into orbit around the sun. It is worth mentioning that the two boosters used for this launch successfully flew themselves back to the ground and landed simultaneously, making for an entertaining finish, but further proof that rockets can indeed be reused.

This ability to reuse technology is integral to the point here: preservation of historical artifacts is an often lauded principle, but what happens when the most pragmatic route is the reuse of those artifacts? The KSC has a museum, and plenty of space travel artifacts, but the historic site has been repurposed to fit modern needs.[2]

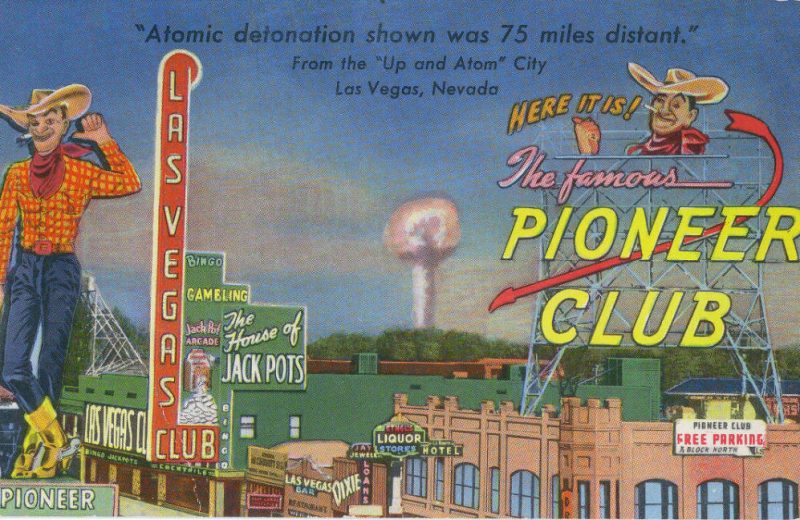

Postcard of the Pioneer Club and Las Vegas Club, Las Vegas, circa 1950s. Image credit: University of

Nevada, Las Vegas, Photo Collection

Closer to home here in Las Vegas, the Nevada Test Site (NTS, or now, the Nevada National Security Site, NNSS) also attempts to balance the problem of preservation versus use. Some may recognize this site as the land underneath the mushroom clouds in most of the pictures of atmospheric nuclear bomb tests from the 1950s and ’60s. Today, it is still an active Department of Energy (DOE) installation. Unlike the KSC which boasts an entire visitor complex complete with a museum, astronaut hall of fame, and “rocket garden” on site, the NTS has an offsite museum near the University of Nevada, Las Vegas that is affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution. The NNSS itself does offer limited tours that are booked for the entire year before January is over (those who booked a private tour with UNLV’s Anthony Graham at the upcoming NCPH Annual Meeting should consider themselves lucky). These tours bring visitors to various sites and facilities in the massive test site, but the standout of the tour is the now famous Sedan Crater, which is currently the only part of the NNSS listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Exterior of Atomic Liquors. Photo credit: Billy Marino

In comparison to Kennedy Space Center’s continued reinvention, the test site is no longer used, and is also not easy to get to. In fact, much of Las Vegas’s contributions to the Cold War are not easily discernible. The museum aside, there are few parts of the city that publicly display this history, and few residents born after the period of testing realize the city’s connection to the Cold War. The CIA plane crash atop Mt. Charleston’s peak was recently memorialized at the Spring Mountains Visitor Gateway far below the crash site, but getting to the wreckage requires one of the more challenging hikes in Southern Nevada. Far easier to spot are the remnants of the popular atomic culture with the first freestanding bar and liquor store, Atomic Liquors, still standing and thriving in downtown Las Vegas.[3]

The challenges of preserving historic sites are too numerous to list, but one major aspect is the tension between preservation and use. For the many sites of the Cold War, they are places with renewed purpose, whether that be continued space exploration or continued study of nuclear technology. Yet, this use requires the dismantling and often reusing of the material objects already imbued with historical value, such as a launchpad or test facility.

The question we must ask ourselves is: which one do we value more? Is preserving massive installations such as those at the KSC or NNSS for visitors to experience worth the pragmatic issues that come along with maintaining the space on active sites? Or is it better to capture pieces of those histories in museums and allow the landscapes and material objects to be remade? These are questions worth pondering for everyone, not just historians. The answers to these questions have consequences beyond historic sites and enter into current tensions with various monuments and institutional names.

~ Billy Marino is an M.A. student in UNLV’s history department, focusing on U.S. environmental history in the Cold War. Billy minors in public history and has contributed to several exhibitions, including Thriller Villa: The Man in the Mirror and Mr. Showmanship and The Liberace Garage.

[1] See Marina Koren, “SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy is Ready for its Historic Flight,” The Atlantic, February 5, 2018. Accessed February 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/02/spacex-falcon-heavy-launch-elon-musk/552296/ ; “Falcon-Heavy,” SpaceX, accessed February 2018. http://www.spacex.com/falcon-heavy.

[2] As Roger D. Launius, “Abandoned in Place: Interpreting the U.S. Material Culture of the Moon Race,” The Public Historian 31, no. 3, 2009, points out, the initial Apollo Launch Complex 34 is in a sad state with only a plaque and limited public access.

[3] Billy Marino, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, “Atomic Liquors,” Intermountain Histories, accessed February 2018, http://www.intermountainhistories.org/items/show/29.