Collecting Guantánamo Public Memory

13 September 2013 – Julia Thomas

Guantanamo Public Memory Project, projects, community history, memory, archives, government, human rights

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

When I began working as a researcher with the Guantánamo Public Memory Project (GPMP) in 2011, I knew very little about the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and its uses prior to 9/11. Tasked with compiling resources for university teams across the country to use in the production of their exhibit panels, I commenced an unconventional “tour” of GTMO’s long history through the countless images, manuscripts, and other objects donated by individuals with experience on the base.

Today, as we work to build GPMP’s archives on the Digital Library of the Caribbean and at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library through its Center for Human Rights Documentation and Research, information about new sides of the base continues to emerge. In contrast, the GTMO I first learned about from the evening news remains mysterious and impenetrable, and many personal possessions are considered classified intelligence; they are certainly not yet public records of the past. But because the snapshot photographs, letters, and other personal artifacts included in the archives uniquely document the expansive range of lived experiences GTMO cultivated prior to 9/11, they play an important role in our efforts to understand it today and to envision its future.

For one, the archival materials help humanize history by taking us away from broad ideological narratives and telling us about real people: the acts of agency in the confinement of Haitian and Cuban refugee camps, the bonds forged between Americans and Cubans in the midst of a global Cold War, the moments of leisure enjoyed at a military base. By bringing into focus the spectrum of GTMO’s lived experiences, these artifacts foster a space for dialogue that transcends delineations of time and perspective that can lead to clashes over memory ownership.

These objects can also tell us a lot about the “big picture,” both when we situate them in their relevant historical contexts and when we reflect on their relation to GTMO today.

Cover of What’s Really Cooking in GItmo!, compiled by base residents in 1964, courtesy of Frances Matlock

For example: Frances Miller, who grew up on the base, donated to the Project’s archives an original copy of What’s Really Cooking in Gitmo!, a compilation of recipes that were “among the favorites of the families of the US Naval Base, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.” In the cookbook’s foreword, the group of contributors expressed hope that it would remain important to residents long after their departure from the base, and “bring back fond memories of a ‘unique’ tour of duty in Guantánamo…”

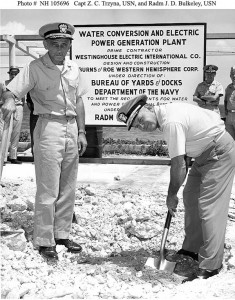

In February of the same year the cookbook was produced, 1964, Fidel Castro shut off the water supply at the base after accusing the US of kidnapping 38 Cuban fishermen for illegally fishing in Florida waters. The water crisis was eventually resolved, and unprecedented autonomy from Cuba established with the construction of a new water plant at the base.

Installation of the base water conversion plant, February 1964, courtesy of the US Navy Historian’s Department

In this context, What’s Really Cooking in Gitmo! is an embodiment of GTMO’s geographical and cultural ambiguity at a time when Cold War tensions were literally boiling. Cuban and Caribbean-influenced dishes appear throughout the book, including recipes for Borderline Bar-b-que Sauce, Cuban Pork Chops and Rice, Cuban Stuffed Potatoes, Tamale Pie, and Puerto Rican Asapao de Gallina. The “Beverages and Brews” chapter provides instructions for concocting a “Guantánamo Frosted Fruit Punch.”

Yet the compilation is also distinctly American and reflects cultural trends of the time accordingly: it offers recipes for dishes like Fluffy Meatloaf, Hamburger Noodle Bake, and Cottage Cheese Salad (a mixture of lime and lemon Jello, canned milk, mayonnaise, chopped nuts and cottage cheese) and reserves a chapter for “Men Only.”

Beyond capturing the essence of a bygone era, What’s Really Cooking at Gitmo! and other historical artifacts help illuminate what has persisted through the years at GTMO. It would be almost three decades before the first refugee detainment camps were established and the strategic value of the lease’s legal ambiguity was fully realized. But today, as in 1964, the base is situated on an island with which US trade is prohibited, new construction projects are underway, and residents even continue to exchange recipes – albeit on Facebook.

But while the archives’ patchwork collection of GTMO’s memories reinforces the permanence of the base, the archives’ absences have important implications as well. Despite policy changes and promises made under the Obama administration, the US War on Terror fundamentally altered the ways in which we will ever be able to access the lived experiences of those who are held at GTMO today. Detainees’ attorneys are subject to heavy National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance, and snippets of testimony during their trials are mysteriously censored; meanwhile many detainees have had their most sacred personal effects confiscated, and some continue to be denied the most basic right to control their own bodies.

Meanwhile, one byproduct of this inaccessibility in the name of national security – in which we can ascertain very little about these people as individuals – is the perseverance of the War on Terror narrative that anyone held at GTMO is an enemy and a terrorist and nothing more. We might reconsider these preconceptions if we could see the detainees in a more human light through the records of their lives at GTMO.

The limited amount of declassified material made by detainees, including poetry and artwork, thus plays a key role in our public engagement efforts. Journalist Tim Fitzimmons, who was able to photograph the pieces of art that were deemed suitable for public consumption and displayed at GTMO in 2011, highlights their importance: “We may never know if the beaches, lanterns, and Middle Eastern lanes of the drawings convey the inner life of the average prisoner. But for now, this handful of drawings is one of the few views of what life is like behind the barbed wire of Guantánamo Bay’s detention center.”

Maybe one day we will be able to know more about the people who are there today. But as construction continues on the remote base, the missing pieces are significant because of what they tell us about this particular state of indefinite detention: it means not knowing whether or not Guantánamo will ever be a memory.

~ Julia Thomas is a Research Associate with the Guantánamo Public Memory Project and an MA candidate at New York University’s Interdisciplinary Program in Humanities and Social Thought.