Conference P(review) #4: Canadian War Museum

16 April 2013 – Jill Dolan

Editor’s note: In preparation for the upcoming NCPH conference in Ottawa, The Public Historian has commissioned a series of Ottawa site reviews, as it does annually for sites in our conference city. These “(p)reviews,” as we’re dubbing them, will inaugurate what we hope will be a growing partnership between The Public Historian and the Public History Commons. Further online post-conference reviews will follow later this spring; we invite readers to comment on these posts as they appear.

Canadian War Museum, 1 Vimy Pl, Ottawa. Tim Cook, Acting Director of Research; Andrew Burtch Curator of “Eleven Women Facing War” and “Khandahar: the Fighting Season;” Peter MacLeod, Curator, Pre-Confederation Canada. Open weekdays between 9 A.M. and 5 P.M., and Thursdays until 8 P.M. Free admission after 4 P.M.

Just a short walk from the Delta Hotel in Ottawa, the Canadian War Museum offers conference attendees an opportunity to see award-winning architecture and experience two photographic exhibits (one open until April 21), in addition to the museum’s expansive exhibits on war and conflict from a Canadian perspective. Visitors can easily spend four or more hours touring the galleries. Below are a few of the highlights that may be of interest to NCPH members.

The Canadian War Museum stands out on the barren land of LeBretton Flats, once covered with a thriving working-class neighborhood, felled by “urban renewal.” Now, nearly forty years later, mixed-used development is beginning to fill in the space. (Photo courtesy of Jo McCutcheon.)

The Canadian War museum moved from its earlier home in the former Archives building to a new purpose-built facility in 2005.[1] The new museum building is a stunning piece of art designed to push visitors to consider the grim reality and devastating consequences of war. Architect Raymond Moriyama is himself a casualty of conflict; at the age of twelve his family was interned in the interior mountains of British Columbia for several years, along with other Japanese-Canadians living on the country’s west coast. He told Maclean’s magazine in 2005 that his design for the war museum began with a sketch of the tree house he built as a boy in that internment camp. The tree house was both a refuge and a place of contemplation and regeneration during a time of conflict, and Moriyama wanted to bring these elements to the design of the War Museum.[2] The building’s low profile resembles a hideout or bunker, while the tall fin rising at the east end is reminiscent of the prow of a ship (the small windows on it spell out “Lest We Forget” in Morse code). Most of the building’s windows are on the east side, facing the sunrise – a symbol of hope – in keeping with Moriyama’s theme of regeneration. Inside, the low ceiling in the entrance hall, combined with the slanted and stark concrete walls, create a slightly claustrophobic and disorienting feeling. This is a building designed to make visitors slightly uncomfortable even before they get to the exhibit galleries.

Two architectural features inside the museum deserve special mention: Memorial Hall and Regeneration Hall. Memorial Hall is a small chamber off the entrance hall, empty except for a single tombstone once used to mark the grave of an unknown soldier in France. The room itself is angled so that the windows high above cast light on the tombstone only once a year – on Remembrance Day, November 11. Regeneration Hall, located at the east end of the building, is also precisely aligned for a symbolic purpose. The tall angled windows of the hall reveal the Peace Tower, on Parliament Hill, built following the First World War to commemorate those killed. As visitors descend the curving staircase the tower disappears from view. At the base of the stairs, in front of the window, is a statue symbolizing hope. All the statues in the hall are plaster models used in the construction of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, designed by Walter Allward and unveiled in 1936. The Vimy Memorial commemorates Canada’s 60,000 dead soldiers during the First World War (more than 10,000 with no known grave). These two sites – Memorial Hall and Regeneration Hall – demonstrate the influence of the First World War on Canadian history, memory and identity.

Especially notable are two temporary photographic exhibits: “Khandahar: The Fighting Season” and “Eleven Women Facing War.” These exhibits highlight the ways that men and women experience war, and prompt reflection about how war and gender have been captured through the camera lens.

“Eleven Women Facing War” tells the personal stories of eleven women’s encounters with armed conflict. International photographer Nick Danziger photographed the women in 2001 in co-operation with the International Red Cross. He returned ten years later to locate the women and see how their lives had changed. The initial photographs were displayed at locations in Paris, the Balkans, and the Middle East, and the current exhibit appeared in Paris and Monaco in 2011. The exhibit will be at the Canadian War Museum until April 21, and will open at the Military Museums in Calgary, Alberta on August 8, 2013.

Although many of Danziger’s excellent photographs can be viewed on his website—and the Red Cross videos from 2001 are also available on the War Museum website—they are worth seeing in the large and airy space of the museum’s John McCrae Gallery. The museum’s temporary exhibit space might easily dwarf the exhibit, but the low lighting and dark colors create a sombre and intimate environment that keep the photographs from getting lost. Each woman’s story is presented separately in a combination of video footage (with audio available on headsets) and photographs.

Two elements of the display make it particularly effective. Danziger has created an arresting visual distinction between the 2001 and the 2011 images by displaying the former in black and white and the latter in color. There is very little contextual information about the conflicts these women have experienced. Visitors are told where the women are and what has happened to them—injury, loss of family member, imprisonment—but there are no timelines here, no political figures. The armies are in the background, the women, fore-fronted. The women’s personal struggles—for formal assistance, for evidence of a loved one’s death—speak to the way war destroys records and resists being documented in a narrative way. For many of these women, the official history of the war matters little; the conflict has knitted itself into the fabric of their lives.

“Khandahar: The Fighting Season” includes fourteen images, highlights from awarding winning Canadian photographer Louie Palu, who, “…launched a personal effort to capture the face of Canada’s war in the Afghan countryside.” The photographs are located in a narrow hallway, and located closely to a large tank, contrasting the space afforded to Danziger’s exhibit. Each image draws the audience into the harsh landscape, the dust, the heat, and pain of war and loss.

The museum’s permanent exhibit is divided chronologically into four galleries, three of which are almost exclusively dedicated to overseas conflicts. This provides visitors with the opportunity to see the ways that global conflicts have been emphasized and curated in different ways.[3] For example, visitors may be interested in the imagery of the poppy, rooted in John McRae’s poem, In Flanders Field, and seen throughout the museum in paintings including some by Turkish artist Hikmet Çetinkay displayed in the windowed cafeteria. Conference attendees more familiar with military and war exhibits in the United States may also be interested in the artifacts and displays related to the battle of Vimy Ridge, which will be commemorated in April 2017.

Domestic conflicts, or “Wars on our soil” are interpreted in Gallery 1, the smallest of the four galleries. In comparatively less space, this gallery covers a large time frame (“earliest times to 1885”) and a diversity of experiences including: pre-contact conflict, colonial and imperial conflict in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the War of 1812, and conflict on the prairies after Confederation in 1867. Updates to this Gallery will be enhanced by the extensive ethno-historical research that has focused on First Nations, Inuit and Métis over the past decade.

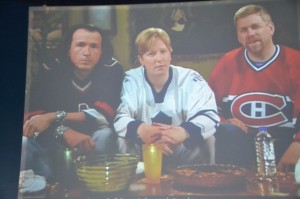

History and Hockey? A must-see film at the Canadian War Museum, 30 Minutes that Changed Canada…and the World: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, offers a take on historic interpretation public historians will love. (Photo courtesy of Jo McCutcheon.)

If you are not able to spend a lot of time in Gallery 1, it is indeed worth stopping in the small theatre to view the film, 30 Minutes that Changed Canada…and the World: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, a ten minute film that appears in French and English and has a two minute break between viewings. The most entertaining and perhaps most curious aspect for non-hockey fans and non-Canadians is the commentaries and interjections by two and then three men sporting Montreal Canadian (French), Toronto Maple Leaf (English) and later, Vancouver Canuck (Aboriginal) hockey jerseys. It is an interesting interpretation of ‘race’ relations and sure to generate discussion and debate among museum visitors and hockey fans!

~Katherine Rollwagen and J.M. McCutcheon, University of Ottawa

[1] The museum is located in an area called LeBreton Flats, which has a story of its own to tell. This large piece of land adjacent to downtown Ottawa used to be a pulsing neighborhood of factories and working-class homes. In the early 1960s it was marked for “urban renewal” and land was expropriated. Nearly 3000 people were displaced and the buildings levelled. Plans for new development on the site were long stalled by the need for soil remediation at former factory sites. Mixed-use development is now proceeding. See Heritage Ottawa, “Heritage on LeBreton Flats: Commemorating the 1962 Expropriation.” http://heritageottawa.org/en/heritage_lebreton_flats_commemorating_1962_expropriation (accessed April 10, 2013).

[2] Christopher Hume, “Architect of Peace,” Macleans (1 May 2005).

[3] The other main galleries are 2: For Crown and Country: The South African and First World Wars, 1885-1931; 3: Forged in Fire: The Second World War, 1931-1945; 4: A Violent Peace: The Cold War, Peacekeeping and Recent Conflicts, 1945 to the Present and The Royal Canadian Legion Hall of Honour: Canada’s Rich History of Honouring and Remembering.