Lessons in interpreting controversial history at a Southern heritage site

15 March 2013 – Evan Kutzler

Part of what drew me to the University of South Carolina’s Ph.D. program in history in 2010 was the opportunity to engage with controversial topics while pursuing an M.A. in public history along the way. The summer after my first year in the program, I found a part-time job with a private non-profit organization looking for someone to produce a new guidebook for an historic property it managed: a farmhouse located on a former plantation in the hills of one of the Border States. The organization had enthusiasm for site improvement but limited resources and few staff with professional training. The experience turned out to be a difficult lesson in taking professional standards as a given and interpreting controversial topics.

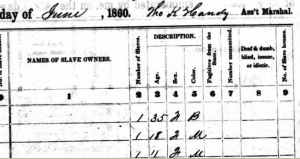

Even traditional sources give a sense of the age, sex, complexion, and genealogy of plantation labor. Although all white members of the household were discussed in detail, final edits removed even the age range of the enslaved. 1860 Federal Slave Schedule.

I was startled at first by the resistance I faced trying to interpret antebellum slavery and the divided sectional loyalty of the family during the American Civil War. The plantation was not unusual to the antebellum South, but the history of the property could not be explained without understanding the nature of the labor force that supported its growth. After the introduction of cotton in the 1850s, the site grew from a farm of 220 acres and 15 slaves in 1850 to a plantation of 28 slaves that produced about 12,000 pounds of cotton a year. Three sons fought in the Confederate Army, but the eldest son and the father took the oath of allegiance to the Union in the summer of 1862 and focused on cotton farming for the rest of the war. The organization that manages the property as an historic site today used economic data and records of Confederate service in the site’s interpretive materials, but much of the information about slavery and divided loyalty within the household did not seem to be of interest to the staff.

Birds’-eye view map showing a plantation house and supporting outbuildings near Columbia, South Carolina, circa 1872. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Maps Division.

My research revealed considerable insights about the lives of the enslaved on this property. The 1860 labor force was quite young: thirteen of the enslaved were under the age of twelve. Most of the enslaved worked on the farm, but others were “hired out” to neighbors and family members. This type of arrangement was common among relatives, neighbors, and sometimes distant hires. More mysterious was a local inquest into the drowning of an enslaved woman named Rachel. There was enough primary evidence to link national stories about race and slavery to the particular historic site.

Yet, present-day local and national politics can influence the stories that are told about local history. When the organization temporarily removed a Confederate flag for cleaning, the director received anonymous threats. Last year, the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) announced an investigation of the nonprofit’s management and the board of directors. Although the latter took place after the guidebook’s publication, it highlights the local subtext of external pressure. These are often easier to discuss during a seminar than during the first weeks of a temporary job. More importantly, these pressures have the potential to stifle complicated interpretations of the past in favor of safety.

Avoid the pressure to whitewash, or self-censor, by defending the inclusion of the whole story from the beginning. Not doing so may encourage the site to make deeper interpretive erasures. Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

This local subtext influenced my writing process. Early into my work it became clear that the curator was uncomfortable interpreting the lives of the enslaved. She preferred the term “farm” over “plantation,” and justified an inattention to slavery on limited records and sensitivity to the family descendants. The curator asked me not to use secondary sources or extrapolate beyond federal census data and select family records. This had the effect of constraining my writing on the outbuildings because it was impossible to contextualize the daily lives of slaves. Instructive topics such as foodways, daily tasks, and working conditions were impossible to address. When the organization began selling the guidebook three months later, the final edits further sanitized slavery and quieted family disunity. Writing the guidebook opened my eyes to the realities of interpreting tough history outside the classroom.

Interpreting a complicated past is challenging, but essential to the field of public history. We should recognize that most historic organizations want to present accurate history. But we should also be sensitive to the pressures small heritage sites face and realize that we may be asked to rewrite a previously established narrative. Although I advocated for a more complicated story, I also felt pressure that resulted in self-censorship. By self-censorship, I mean more than just taking audience into consideration—all writers do that. Self-censorship, on the other hand, occurs when the imagined audience adversely affects the interpretive process. It also requires the perception of an unequal power relationship. For example, I reasoned that if the curator did not want me to write about daily tasks and family dissent, surely I could not discuss the inquest into the drowning death of the enslaved Rachel. I am still confident my basic assumption was right given the other conversations I had with the organization; however, that only takes away some of my feeling of guilt.

The problem of self-censorship did not occur to me before the experience of writing the guidebook. I am not a timid person and I enjoy lively discussion. Yet graduate students and young professionals are probably more likely than others to feel the pressure to avoid controversy. This is not unique to being “in the trenches” of public history; in fact, the awareness of expendability is present in graduate school employment as well. The classroom allows for greater intellectual freedom, but successful graduate students do not pretend they have tenure when it comes to assistantships or department issues. Knowing how to choose battles is a survival method, but this can also leave one vulnerable to self-censorship when they want to apply their training in the workplace. The knowledge that one’s employment is contingent tempers intellectual creativity.

Come prepared to defend the inclusion of all the buildings on the historic landscape and all the people in the household. Image courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina.

This is not to suggest that we rewrite old interpretations and try to avoid the complicated past. We cannot do that. Had I defended interpreting Rachel’s mysterious death with the deaths of other household members, which were included in the published version, it might have been easier to make the case for interpreting the lives of all the enslaved. It is unlikely that a graduate degree would have made much difference in what happened that summer. The staff and the board of directors were all local experts practicing local history. Advanced degrees do not necessarily carry the same weight outside circles of similarly-trained people. Moving forward, what we should do is arrive prepared to offer sound justifications for interpreting the whole household. Coming armed with literature not only about historiographical content but also about standards in historic site interpretation would have made for an easier fight. Having reviews about historic sites that take a holistic approach—and those that do not—might have made a more compelling argument to curators worried about revenue and prestige. Coming prepared to start a dialogue will produce a better experience because you will be more persuasive and less likely to compromise on professional standards.

Graduate students and young professionals have the opportunity to strengthen the dialogue between professional historians and the many small heritage sites around the country. Come prepared to explain trends in public history and expect to face some resistance to interpretations that challenge old assumptions. Avoid self-censorship by coming prepared to discuss standards in historical scholarship. Keep in mind that not everyone who practices history recognizes the value of professional training. And lastly, take pride in sharing the importance of frameworks that interpret the whole household.

Evan Kutzler is a third-year Ph.D. student in U.S. History since 1789 at the University of South Carolina. He has a B.A. in History from Centre College (2010) and an M.A. in Public History from the University of South Carolina (2012). In addition to public history, Evan studies sensory history and captivity experience during the American Civil War under the direction of Mark M. Smith.

I’m surprised but not surprised that this particular site wanted to silence the interpretation of slavery in favor of keeping the locals and the family happy. It is disheartening that many sites either cave to pressure or just don’t approach the subject of slavery because they know there’s going to be backlash, and even more so that there are threats being made to insure the story goes untold.