The Cuban refugee experience of Guantánamo Bay

18 November 2013 – Aurora De Armendi

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

Remembering, an act of courage.

Speaking and listening, a gesture of empathy.

My understanding of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) comes primarily from my experiences as a Cuban refugee between the years 1994-1995 after the Balsero Rafter Crisis but also through my attempt to shed light on the complexity of the Cuban Diaspora via my project EntreVistas and most recently by learning and participating in the Guantánamo Public Memory Project. In 2008, I began interviewing Cuban immigrants mostly living in the United States from different waves of migration in Cuban history: the Early Exiles of the 1960s, the Mariel Boatlift immigrants of the 1980s and the Balseros of 1994.

January 8, 2008 – Caguas, Puerto Rico

I placed a video camera in front of my father, handing him a microphone. “What is your name?” I asked. He looked at me in silence. At the time he was serving as a volunteer doctor in Puerto Rico. I wanted to ask him about how he felt about his decision to leave Cuba and the aftermath but ended up surrendering, understanding that he wasn’t ready to speak, at least not in front of a video camera. He went to the balcony to smoke a cigarette.

August 6, 2008 – Hialeah, Florida

It was noon when a friend introduced me to Antonio. Telling him I was also a Balsera[1], I asked if we could talk. He welcomed me onto his large terrace to sit at a table and chairs. I readied my equipment and asked him to introduce himself. “My name is Antonio Díaz Hernández,” he started and without interruption he spoke for the duration of 31 minutes and four seconds. He told me about his time in the sea and his experiences as a refugee detained at various camps within GTMO, as well as his life in South Florida for the last 14 years. Antonio finished his monologue by saying:

EntreVistas, Antonio Díaz Hernández (Last two frames of his interview), 31min, 4 sec. Photo Credit: Aurora de Armendi

“This month, the 30th, I will be 60 years old and I feel very aged because I have made tremendous efforts to go on but I feel very happy about being able to at least do this that I’m doing right now, to talk freely about my past. Many thanks for giving me this opportunity of telling you this tale, one more of those who came in 1994. Thank you.”

As Antonio said these words he didn’t look at the camera but straight into my eyes. Then, he smiled, stood up, and left the picture frame. For how long had he been waiting for this opportunity– for a moment to share his story?

Sometime in 2009

While working on the production of EntreVistas, I would visit my parents in Fort Lauderdale. During one of those visits I stopped at the University of Miami, Cuban Heritage Collection to see its archives regarding the Cuban Rafter Crisis and documents pertaining to Cuban refugees in Guantánamo. Jorge Mulet, a fellow at this institution at the time, handed to me the documents I had requested. They were all stored in manila folders with photocopies of newspaper clippings, drawings, and writings from Cuban refugees.

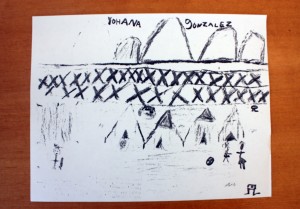

University of Miami, Cuban Heritage Collection (Drawing by Johana González of a camp at GTMO) Photo credit: Aurora De Armend

As I was photographing some of the documents, Jorge approached me and said that he had a surprise for me. After a few minutes he came back and handed me two black plastic wristbands.

“Major Paschall observed that many of the refugees had managed to remove the plastic wristband. Some chewed through them, or cut them off with homemade knives. Although their records could always be found using the Touch print scanner, time and material were wasted replacing lost wristband[s]. He suggested reinforcing the plastic wristband with metal filaments.”[2]

The University of Miami, Cuban Heritage Collection (The wristbands of Jorge Mulet and a family member: Deployable Mass Population Identification and Tracking wristband.)

Photo credit: Aurora De Armendi

Suddenly, seeing this object – touching it – brought to my memory the anxiety I had felt every time that my right wrist had been scanned when entering or exiting the camps in GTMO, yet I still listened to Jorge’s story. He spoke about these objects with such care that I could sense these wristbands had either belonged to him or someone close to him. I didn’t know how to handle the strange fondness with which I was relating to these wristbands. How could a device such as an electronic ID bracelet – the very emblem of the condition of refuge – spark this kind of remembrance?

“Among the refugees, reactions were often surprising. Lyonel and David, two English-speaking brothers from Port-au-Prince, said they actually liked it. ‘When they put this on me, mahn,’ said Lyonel, ‘I knew that they were taking me seriously, and that something was finally going to happen for me.’ David agreed. ‘When I saw my name and picture in that computer, I knew things were gonna be fine.’ David also sees the wristband as a symbol of the refugee’s solidarity in living through a shared emergency.”[3]

Jorge said he wore the small wristband on his ankle since he was only five years old at the time. That’s why it bears so many scratches on the top front surface. The night before coming to the United States, one of the marines let him keep it as a souvenir. He later donated it to The Cuban Heritage Collection.

October 2, 2012 – New York, NY

I was invited by Liz Ševčenko, director of the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, to speak to her students about the EntreVistas project in her Topics in Museum Studies class at New York University. At the time, her students were selecting the photographs and writing the text that would best communicate from various perspectives the collective experience of Cuban refugees at the US Naval Base of Guantánamo Bay. The culmination of this work was going to be exhibited at NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life Windows Gallery along with 11 other exhibition panels, each one focusing on the plural history of Guantánamo.

The process of working on EntreVistas and the collaborative work conducted by the Guantánamo Public Memory Project engage the desire to remember and recollect GTMO’s history. The material residue of GTMO’s detainees – that is Jorge’s identification wristband, Johana González’s drawing, or the archives of the Guantánamo Public Memory Project – these are powerful and necessary tools for educating and generating empathy with the general public as we continue these national dialogues surrounding the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay as a site of detention for some but as a place of work and dwelling for others.

~ Aurora De Armendi is an interdisciplinary artist and teacher. She was born in Havana, Cuba, and received a BFA from The Cooper Union School of Art (2005) and an MFA from The University of Iowa (2009). Her work has been exhibited at the Old Capitol Museum in Iowa City, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, International Print Center of New York, the Bronx Calling: The Second AIM Biennial, and The Center for Book Arts, among other venues.

[1] Balsero/a, term used to describe Cubans who left their country in homemade rafts during the 1994 exodus. The ones that survived were rescued and detained in GTMO. There were 33,000 Cubans at GTMO.

[2] Lynne Brakeman, contributing editor, “New DoD system tracks refugees: Navy deploys RF/ID-based human tracking system to cope with HaitianCuban Exodus,” Automatic ID News 10, no. 13 (December 1994): 14-17.

[3] Ibid.

Hello This surely bring back a whole bunch of past memories that somehow still linger to this days. Could you send me info of this place where items are shown, or any other memorabilia of those times like picture, refugees art and so

Good reading

Hello Martin

Thank you for your comment and interest on the history of Gtmo.

You can visit this site:

Blog.gitmomemory.org and under RESOURCES you may find more information about the collection for this project. You can also check The University of Miami Library to learn more about the Balsero Crisis and see documents and photographs pertaining to this period. Florida International University holds a small archive as well.

Thanks again,

Aurora

Are you interested in pictures of the actual camp. I have family that was picked out of the ocean on a failed trip, in a home make raft trying to reach Florida The Coast Guard took the survivors to Guantánamo Bay where they were imprisoned for years.

I served on one of the USCG Cutters that was stationed in the Florida Straits. I’m working on a project dealing with atonement. Would you be willing to be in conversation with me? I would also be interested in pictures from that time.

Very respectfully – Heather

Hello Heather. I was 8 years old when I was rescued by the USCG on Aug 24th, 1994. On behalf of the many lives you helped save, THANK YOU! The moment when we saw one of those majestic USCG cutters next to us is one we shall never forget as it meant freedom, help, survival and so much more. I lived in Guantanamo from Aug ‘94 – March ‘95 and have many pictures I can share if you’d like.

I worked in the camps for U.S. Dept of Justice Community Relations Service. It was a life-changing experience learning about the balseros and life in Cuba.