Engaging contested memory in the classroom

26 February 2018 – Lara Kelland and Sarah McCoy

Editor’s note: In this latest post in our series on teaching with articles from The Public Historian, Professor Lara Kelland and MA student Sarah McCoy discuss their respective experiences using Christine Rieser Robbins and Mark W. Robbins’s essay, “Engaging the Contested Memory of the Public Square: Community Collaboration, Archaeology, and Oral History at Corpus Christi’s Artesian Park” (The Public Historian 36, no. 2 [May 2014]), in conversation with one another. We welcome comments and further suggestions of articles you have used! If you have a TPH article that is a favorite in your classroom, please let us know. You can send your suggestions to [email protected].

Artesian Park, Corpus Christi, Texas, ca. 1930-45. Image Credit: Tichnor Brothers Collection, Boston Public Library.

Lara Kelland:

In my first pass at teaching Introduction to Public History in our MA public history track at the University of Louisville, in 2015, I read through recent issues of The Public Historian to select a few articles, hoping they would fit into the topical approach I was planning for the class. While many who have gone before me have approached the introductory course as an array of subfields, leading students through considerations of archives, museums, historic preservation, education, digital history, and the like, I decided I wanted to raise more conceptual issues that transcended the bounds of those discrete professional practices. Christine Reiser Robbins and Mark W. Robbins’s “Engaging the Contested Memory of the Public Square: Community Collaboration, Archaeology, and Oral History at Corpus Christi’s Artesian Park” was immediately appealing to me for this purpose, and it has held up well through two iterations of class discussions.

The first time I used this article in teaching, I assigned it during a week intended to provoke conversations about spatial memory and interpretation. Paired with a chapter from Dolores Hayden’s The Power of Place and Pierre Nora’s classic essay “Between Memory and History,” this article served to introduce students to the paired analytic concepts of space and place. In this instance, the Robbins and Robbins piece served as an applied example of the ways in which communities imbue urban public space with historical meaning, creating a sense of place. It also gave us an instance to map out Hayden’s observations about race- and class-based relations to urban landscapes. And, indeed, it served to enrich our later discussions with a real-life example of contested interpretations in urban space.

When I settled in this past summer to prepare to teach the course a second time, I paired it with a chapter from Michael Frisch’s A Shared Authority to spark a discussion on the topical theme of interpretation. My vision was that Frisch could serve as an introduction to the central organizing principle of our field, and that the Artesian Park story would act as a case study, thirty or so years after the emergence of the concept. Although I have taught Frisch in a variety of classes related to both public and oral history methods, I never find myself satisfied with the way the discussion goes. I hoped that having a more applied article to discuss alongside might help us more deeply analyze the more theoretical text. It was a lot of responsibility to put on the shoulders of one essay, but in many ways it lived up to it.

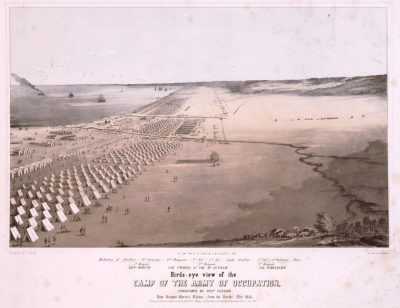

Daniel Whiting’s 1845 lithograph of Gen. Zachary Taylor’s encampment at Artesian Park, the inspiration for a contested, and failed, memorial of the Mexican-American War at Artesian Park. Image credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division LC-USZC4-4557.

We worked on a collectively authored class document to define keywords and create a glossary based on our readings. Through this, we unpacked that for Frisch, memory is a historical subject worth study, that forms of remembering and historical narratives tell us as much about the present as they do about the past, and that forgetting happens when the past is divorced from the present. After some close reading and defining of terms, we moved on to the Robbins and Robbins piece. Immediately, rather than a pregnant silence following my questions, students jumped in, eager to discuss the tensions regarding the memory of Artesian Park. This article also prompted questions about truth and authenticity in public history, as students grappled with how such diffuse and even contradictory narratives about the past could uneasily coexist in one space. I gave students time to parse the notion of truth in representations of the past, and we circled around toward accepting that multiple perspectives can coexist. We also discovered that the goal of public history work is to recognize how power flows through such narratives and that it was our task in our current cultural moment to hold space for those marginalized perspectives.

Sarah McCoy:

As a first year graduate student at the University of Louisville, I am just beginning my public history studies. Reading “Engaging the Contested Memory of the Public Square,” complemented by a chapter in Michael Frisch’s A Shared Authority, for one of our first classes was a great introduction to issues in the field. Robbins and Robbins explore Frisch’s idea of shared authority and how it can be used by public historians with the example of the Artesian Park Project in Corpus Christi, Texas, discussing how the project was to address both the known as well as the untold history of the town and park. The key to the Artesian Park Project is the collaboration Robbins and Robbins employed, including community involvement in both recording and discovering history. Through oral histories and archaeological methods, the history of Artesian Park came to view. This kind of process is an excellent example of Frisch’s idea of shared authority, as the leaders of the project worked with the members of the community to tell their history. The people who engaged in this product actively participated in creating the history of the park, and the process allowed diverse groups of people to tell different stories of the same area. This mixing of professional interpretations and public perspectives provides an example of what public history practitioners should be doing.

In class discussion with other students also beginning their public history studies, we talked about how the Artesian Park Project provides a model for the public historian to follow in his or her work. To our minds, the goal of the public historian is to go beyond the narrative, incorporating all perspectives, and through that collaboration create community healing. There are so many issues concerning underrepresented populations and the history told at historic sites and museums. The avoidance of a group’s narrative can be destructive and can perpetuate historical trauma. Public history, as exemplified by Robbins and Robbins, allows for those stories to be told, and through the process of shared authority at historic sites, healing can begin for those communities.

Using this article in the classroom gave me an insight into what the field of public history is becoming and the things that I might face as a public historian. Frisch’s idea of shared authority, animated by Robbins and Robbins in the Artesian Park Project, showed me not only what it means to be a public historian, but how I can actively engage in public history and let those untold stories to be heard. Growing up, I always knew that I wanted to make a difference and help people, but I never knew that I could accomplish that through my love for history. “Engaging the Contested Memory of the Public Square” is an excellent introduction to the public history field, and I know it has encouraged me to continue my studies and to look forward to the career that is ahead of me.

Lara Kelland:

In reflection, I am pleased to know that students took away from the article some of the challenges facing public historians who tackle projects that encompass contested narratives. My moderate concerns about incorporating such a piece early in the semester proved unfounded, and I am also pleased that my students made connections across topics, as they invoked this piece in relation to Denise Meringolo’s fantastic monograph Museums, Monuments, and National Parks, situating the Corpus Christi project in the long trajectory of engaging publics. One small critique I have of the Robbins and Robbins piece, from a teaching perspective, hinges on the fact that the traditionally hegemonic voices, what the authors call the nostalgic memories, weren’t engaged in the most recent of projects, but rather were corrected. Although project leaders clearly set out to add the voices of people who had long been marginalized, readers don’t really get a sense of what actually putting contested memories into conversation with one another might look like. Of course the work of public historians in so many instances primarily lies in the bringing forth of silenced voices from marginalized communities, but it would be most useful to have a project recounted that grappled with contestation in the present. Nonetheless, this is a small criticism that lies beyond the goals of the Corpus Christi project leaders. Yet this desire does not diminish the fact that this article serves to introduce students to the complex history of commemorative practice in the United States, as well as model good collaborative public history practice at a challenging and contested historic site.

~ Lara Kelland teaches and practices public history at the University of Louisville. Her upcoming book, Clio’s Foot Soldiers: Twentieth-Century US Social Movements and the Uses of Collective Memory, looks at the use of history in twentieth-century social movements and will be published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 2018. She is the curator for an upcoming exhibit and digital map on the Kentucky civil rights movement at Kentucky Center for African American Heritage and her new research project is engaging oppositional collective memory and heritage tourism in Puerto Rico.