Engaging to preserve: Building a preservation-minded community through Twitter

29 October 2015 – Caroline Nye Stevens

Over the course of ten weeks this past spring, I explored, blogged, and tweeted my way through twenty of Providence’s endangered properties. The challenge came to me by way of the Providence Preservation Society (PPS), which is celebrating the twentieth anniversary of their Most Endangered Properties (MEP) program this year. What began as a straightforward project of disseminating information developed into a dynamic experience of knowledge-sharing around the built environment. The project strengthened and empowered Providence’s community of scholars, experts, and activists.

Twice a week, I posted a new building from PPS’s endangered properties program to the MEP20 blog, exploring success stories and losses and documenting several buildings that continue to struggle. I interviewed historians, librarians, archivists, building owners, residents, and community leaders. The most interesting pieces of information, however, came from using social media to solicit opinions, questions, photographs, and research on all twenty buildings. As a result, we explored history and preservation in Providence together.

All of this information was collected into a Storify for each building and shared on the MEP20 blog, telling a far more complete and interesting story of the buildings. In some cases the building posts completely relied on community knowledge and research. A former iron foundry, called the Phenix building, is a great example.

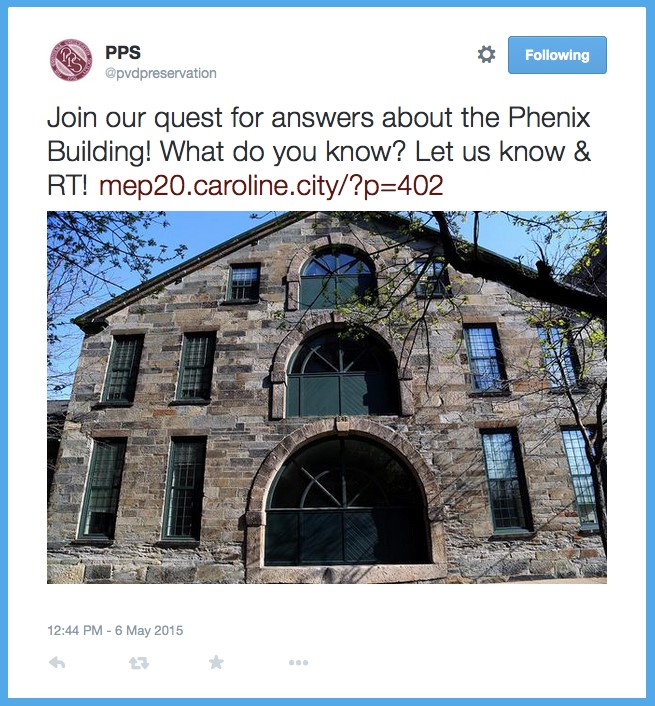

There is surprisingly little published about this former industrial building, which stands out in the city due to its granite façade and prominent tri-level arched entrance. We knew that the building was built in 1848 as a foundry for producing textile-printing machines at a time when Rhode Island’s textile mills were growing exponentially. Most of the other information I had was based on rumors and hearsay recounted to me by the employees currently working in the building.

There is surprisingly little published about this former industrial building, which stands out in the city due to its granite façade and prominent tri-level arched entrance. We knew that the building was built in 1848 as a foundry for producing textile-printing machines at a time when Rhode Island’s textile mills were growing exponentially. Most of the other information I had was based on rumors and hearsay recounted to me by the employees currently working in the building.

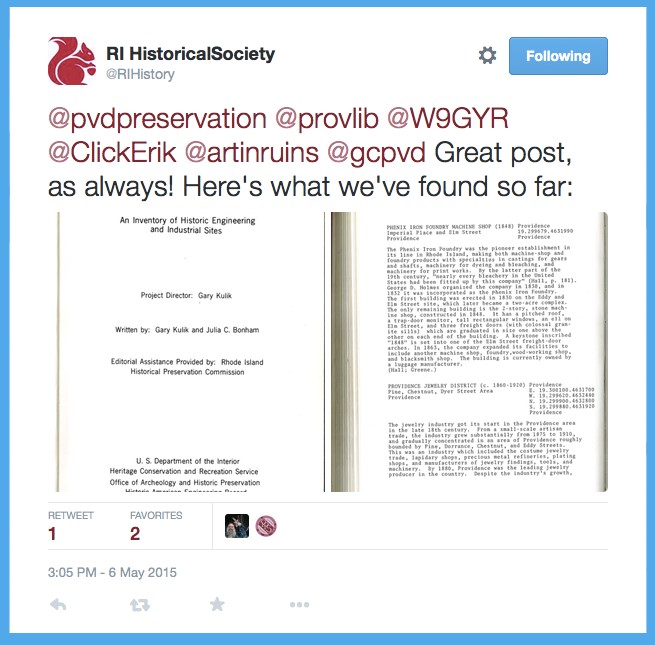

PPS’s Twitter followers rose to the challenge by digging through archives and locating old Sanborn Maps. The Rhode Island Historical Society (@RIHistory) came forward with Rhode Island’s “Inventory of Historic Engineering and Industrial Sites,” which stated that by the late nineteenth century, “nearly every bleachery in the country had been fitted by the [Phenix] Company.” From this book scan shared over Twitter, we also learned that the complex used to be much bigger in size, and at the time of writing (1978), a luggage manufacturer operated out of the building.

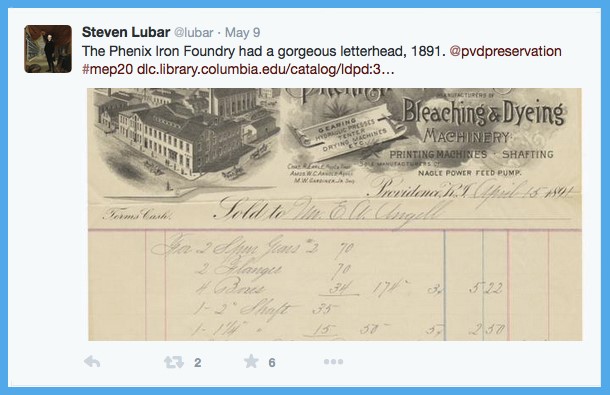

Twitter follower Steven Lubar (@Lubar) found an old Sanborn Map picturing the building and wondered if the smaller buildings surrounding it might be workers cottages. He also tracked down 1891 Phenix Company letterhead in which the company advertised itself as the “Sole Manufacturer of the Nagle Power Feed Pump.”

Twitter follower Steven Lubar (@Lubar) found an old Sanborn Map picturing the building and wondered if the smaller buildings surrounding it might be workers cottages. He also tracked down 1891 Phenix Company letterhead in which the company advertised itself as the “Sole Manufacturer of the Nagle Power Feed Pump.”

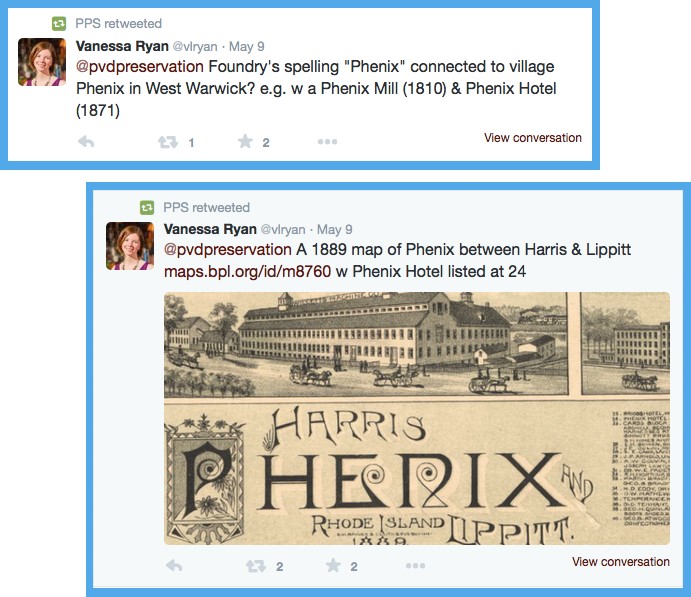

Twitter follower Vanessa Ryan (@vlryan) solved the mystery of the Phenix’s name (which I wrongly assumed was a misspelling of Phoenix) by relating it to a village in the neighboring town of West Warwick by the name of Phenix. She dug up an 1889 map of the town that also featured a Phenix Hotel and Phenix Mill and wondered if a building on the map credited to “Holmes” might be the George D. Holmes who founded Phenix Iron Foundry.

Twitter follower Vanessa Ryan (@vlryan) solved the mystery of the Phenix’s name (which I wrongly assumed was a misspelling of Phoenix) by relating it to a village in the neighboring town of West Warwick by the name of Phenix. She dug up an 1889 map of the town that also featured a Phenix Hotel and Phenix Mill and wondered if a building on the map credited to “Holmes” might be the George D. Holmes who founded Phenix Iron Foundry.

Through solving the mysteries behind the Phenix Building and nineteen other Providence structures, together we became treasure hunters, storytellers, and preservationists. As a newcomer to Providence, it was easy for me to admit my own ignorance about the buildings and share authority with others. What made the MEP20 challenge so exciting was that we were all on a quest for knowledge together. Crowdsourcing research and knowledge provided a wealth of information about the Phenix building and allowed me to acknowledge and celebrate Providence’s community of historians and preservationists.

Through solving the mysteries behind the Phenix Building and nineteen other Providence structures, together we became treasure hunters, storytellers, and preservationists. As a newcomer to Providence, it was easy for me to admit my own ignorance about the buildings and share authority with others. What made the MEP20 challenge so exciting was that we were all on a quest for knowledge together. Crowdsourcing research and knowledge provided a wealth of information about the Phenix building and allowed me to acknowledge and celebrate Providence’s community of historians and preservationists.

Because our dialogue took place publicly on Twitter, the reach of the project was greatly expanded. Over the course of ten weeks, MEP20 grew PPS’s Twitter following by 25%, from 700 to 880 followers over the course of ten weeks. Much more significant was the increase in Twitter engagement that MEP20 fostered. Twitter impressions increased by 539% (from 25.9K to 165.6K) and the number of people replying to PPS tweets increased by 3750% (from 10 to 375 replies). PPS’s public engagement through Twitter before the MEP20 project was limited at best, but with a little effort that changed significantly. Through both conducting interviews and tweeting on behalf of PPS, I was introduced to many people. While I only know most of them virtually, I think all of them feel more involved in the PPS community and empowered as preservationists and scholars as a result of MEP20.

Growing your organization’s social media following is of course a worthy goal, but it shouldn’t be the only goal. What’s more important is to use social media as a means of building community. Continuing to empower and engage the public via social media platforms will grow PPS’s community and augment the organization’s impact on the city.

~ Caroline Nye Stevens has worked as a program manager, architectural guide, and independent blogger, exploring ways of bringing the diverse architectural landscape and vibrant history of cities to life for others. Formerly the manager of Chicago’s largest architecture festival, Open House Chicago, she is currently a graduate student in Brown University’s Public Humanities program.