Hidden in plain sight: Cemeteries and civil rights

15 October 2018 – Mimi Eisen

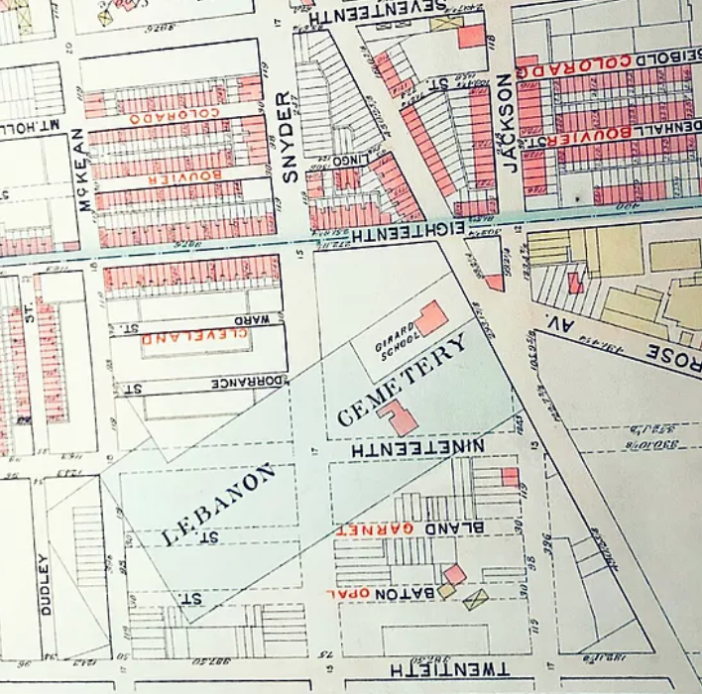

A late-nineteenth-century Philadelphia atlas marking of Lebanon Cemetery, an affluent black burial ground that has long since faded from the city’s maps and popular awareness. George Washington Bromley. Atlas of the city of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, Penn.: G.W. Bromley & Co, 1895. Image credit: Mimi Eisen

In 1849, a community of black Philadelphians secured a plot of land devoted to preserving the rights of their dead kin—from dignified burial, to peaceful rest, to honorable remembrance. Lebanon Cemetery was an answer to the city’s expansive white-only cemeteries and a sanctuary from persistent racial terror and civil rights violations. Until it wasn’t. Violence against black bodies was not limited to the living.

By the mid-1880s, Lebanon was plagued with ghoulish scandal: a group of white men had made a business out of disinterring black bodies and selling them to Jefferson Medical College, where they were dissected in anatomy class. The African American community urged recourse for their beloved, desecrated dead and cried for justice outside of police stations and court houses, but the suspected overseer of the grave-robbing was easily acquitted. Lebanon fell into disrepair and, surrounded by estate and factory owners eager to absorb the land, was closed by the city at the turn of the century. The once-sanctuary for African Americans was lost and most Philadelphians were unaware of its existence. Today, a bus stop stands at the center of where Lebanon used to be. There is no historical marker to capture its memory, to pay homage to its history. All that remains of the cemetery are tucked-away old diagrams, photographs, administrative documents, and a legacy worth remembering.

I entered graduate school to hone the skills of a professional historian and develop projects that increase the accessibility of narratives of underrepresented people to the general public. Much of my research is grounded in connecting today’s realities to the last few decades of the nineteenth century, an era of radical, unprecedented social and legal progress quickly followed by a massive white supremacist rollback of those achievements. How were the rights and lives of black Americans—in life and death—contested, protected, and memorialized in nineteenth-century America? How about today? And what are the stakes for the present day?

This past spring, I developed a website detailing the stories of three cemeteries, including Lebanon, and their present-day resonances. Civil Rights After Life uses my research on cemeteries and civil rights in the late-nineteenth-century American North as a new, public entry point into contemporary discussions of race and memory. Relatively little scholarship exists on the subject; yet, throughout American history, cemeteries have constituted sites of sanctity and honor, symbols of freedom and autonomy carved into contested landscapes. Their disruption or neglect often eludes popular awareness, while violating the civil rights and memory of those who inhabited them. My site, along with related projects (Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, Preserving African American Historic Places, The Coral Gables Museum, The Locust Grove African-American Cemetery Restoration Project, and People Inc., to name a few), aims to illuminate and preserve the neglected, collective histories of these spaces.

Mount Moriah’s beautiful-but-crumbling front gate, where the barring of a black citizen from interment sparked a Pennsylvania Supreme Court case in 1876. The cemetery was officially abandoned in 2011. Front Gate of Mount Moriah Cemetery. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photograph taken on March 24, 2018. Photo credit: Mimi Eisen

My research narrowed to the burial grounds of my native Philadelphia, once a popular destination for fugitive slaves and a long-thriving black community. Philadelphia is the closest major city to Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil, and a site of storied, seminal commemoration. The city holds a wealth of fascinating yet troubling hidden histories. Careful research in both digital archives and local repositories brought three cemeteries to the fore as particularly compelling: Lebanon, Mount Moriah, and Philadelphia National Cemetery. In their own ways, each cemetery’s story illuminates longstanding pushes for racial equity and white supremacy’s consistent backlash. They also show that memorialization is a potent tool. It gestures to which people and events are worth remembering and demonstrates the power of those who get to choose which histories are honored in public spaces. Consequently, these stories ask readers to question celebratory master narratives that frame progress as a straight line while shrouding persistent racial inequities.

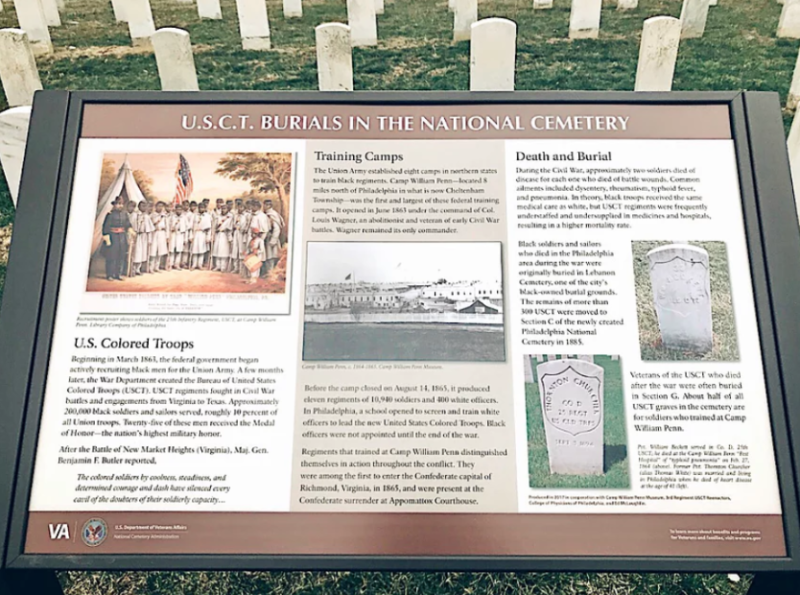

Philadelphia National Cemetery’s storyboard honoring U.S. Colored Troops, which was installed in 2017 after a backlash against a 2015 150-year anniversary commemoration that honored Confederate troops

but omitted the U.S.C.T. U.S.C.T. Burials Storyboard at Philadelphia National Cemetery. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Photograph taken on March 25, 2018. Photo credit: Mimi Eisen

For instance, in a commemorative misstep as recent as 2015, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) installed three storyboards to memorialize Philadelphia National Cemetery’s Civil War-era founding and legacy. One storyboard highlighted it as the oldest of four national cemeteries in the region, another marked the interment of the youngest brigadier general, and the last honored the 184 Confederates buried there following the Battle of Gettysburg. There was no storyboard to honor the interred U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Why did the VA deem it appropriate to install an honorary informational panel for white soldiers who fought against the United States, but not for black soldiers who fought to preserve it? At the request of multiple individuals and historical preservation groups, the VA has since produced and installed a storyboard to highlight the importance of the USCT to the history of the cemetery and the nation at large. But consciously or not, the privileging of white soldiers who fought to preserve the institution of slavery over black soldiers who fought to preserve the Union is more than troubling. It reflects a larger system that too often has favored a whitewashed past, present, and future at the expense of all others.

For this reason, two of the three main content tabs of the site are devoted to the lesser-known histories of these three cemeteries. On “The Cemeteries” page, visitors can read brief blurbs that distill what I consider the “so what?” of these stories—they include the basic names and dates associated with the cemeteries’ histories, but also summaries of how each one contributes to a larger discussion of race, civil rights, and memorialization today. Below the blurbs are zoomable photos of each cemetery from an 1895 atlas, which I first used to locate prominent burial grounds in the Philadelphia region. But they are also helpful in bringing the stories to life by grounding them in place. Visitors can see exact locations of each cemetery in the city: nearby street names and neighborhoods make them easily relevant, which is particularly needed for Lebanon. Of the three, it is both the only exclusively black cemetery and the only one to have long since disappeared from Philadelphia’s landscape. Side by side, these maps tether the cemeteries to present-day and nineteenth-century America alike, and prompt consideration of their starkly different trajectories.

Visitors can easily click between “The Cemeteries” page and its companion, “The Stories.” There, they can read in detail about seminal events in each cemetery’s history, from grave-robbing incidents to lawful desegregation to legacies of racial stratification in the twenty-first century. They can also inspect more related images – a mix of archival material and present-day photos to augment the stories and reassert the past as present.

The final content page is labeled “Today” and brings the project fully into the here and now by spotlighting a few related public history projects in the Philadelphia area. As part of Monument Lab, these particular art installations subverted traditional patriotic master narratives by mapping marginalized black experiences onto prominent whitewashed public spaces. And they did so in a variety of ways: one was a hidden history walking tour smartphone app, another a black power sculpture, and the last a black veterans mural. For those most interested in the traditional monograph, check out the “Further Reading” page.

There are many media through which we can generate public work that impels critical thought and honest discussion about American democracy’s contradictory past and its afterlife in the present. My digital history project is one such attempt, but there are many more hidden histories worth illuminating. In so doing, we become better equipped to reckon with America’s past and meet today’s realities.

~ Mimi Eisen is a 2018 graduate of Brown University, where she obtained a Master of Arts in American history with a secondary focus in digital public humanities. Her work centers on transferring critical underrepresented histories from the academy to the public sphere. Contact her at [email protected].

I would like to make a few comments on the section about the Philadelphia National Cemetery. Although several groups helped the dedication at the Cemetery for the storyboard about the black Civil War soldiers and sailors buried there, I was the one and was alone for several years gathering information on the burials. My name Edward G. McLaughlin and it can be found the storyboard. It was not a slight that the Veterans Administration did not initially install that storyboard at the timing of the three other storyboards installed earlier. The true fact was that the number of these soldiers and sailors buried there was lost to history, no one counted them, until I did massive research on their burials. I gathered a rather large database, then went on a speaking tour asking for support letters so I can petition the VA for the storyboard. The VA was most gracious when they realized what they had in that Cemetery. Please go to the Camp William Penn website (database and archives) to see a massive database on the soldiers. Also, I recommend two of my books on the subject, “The Cemetery Monument Hidden in Plain View”, which tells a bit of the history of the Cemetery and “Slaves and Soldiers in the Cemetery” which discuss what I believe to be the largest number of one-time slaves buried north of the Mason-Dixon line. You may simply type in my name, “Edward G. McLaughlin” on Amazon Books to see all of the books on the subject.