Historic preservation shines a light on a dark past

28 July 2015 – David Rotenstein

preservation, community history, government, The Public Historian, National Historic Preservation Act commemoration

Editor’s note: This post continues a series commemorating the anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act by examining a past article published in The Public Historian, describing its significance and relating it to contemporary conversations in historic preservation.

Between 2011 and 2014, the city of Decatur, Georgia, demolished 200 public housing units built in 1940, under the auspices of slum clearance. In 2013, Decatur’s two city-owned former equalization schools were demolished for a new civic complex and police headquarters. In one gentrifying neighborhood, the private sector sent more than 120 former African American homes to landfills, continuing a cycle of serial displacement begun a century ago. In another neighborhood, a developer demolished a historic black church to clear land for new upscale townhomes. The widespread disappearance of African American landmarks began just two years after the City of Decatur released a citywide historic resources survey that made no mention of the community’s black residents, past and present, nor their historic places.1

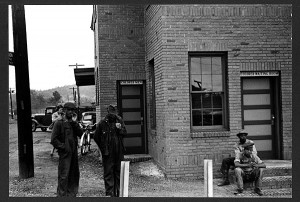

Robert Weyeneth’s 2005 article, “The Architecture of Racial Segregation: The Challenges of Preserving a Problematical Past” [The Public Historian 27, no. 4 (2005): 11-44] gives readers a panoramic view of racialized space and its place in history and historic preservation. Weyeneth drills down to the period between 1890 and 1960 in the American South to examine the ways new buildings were designed and built to conform to what he calls the “spatial strategies of white supremacy” (p. 12). More than a half-century later, those familiar spatial strategies are evident in contemporary Decatur and other cities with municipal growth policies that embrace gentrification and demographic inversion. The result in cities large and small is the resegregation of people and landscapes.

Decatur’s first African American city commissioner deftly connected the threads linking segregation, then urban renewal, and finally gentrification in her city. She has watched black Decatur disappear over the 66 years she has lived there. She compared today’s gentrification with the last century’s urban renewal. “It feels that way because the people are gone,” Elizabeth Wilson told me in 2012. As I began documenting the erasure of African Americans from the historical record in Decatur, some residents there began to recognize the significance of what was being lost. “I work in Decatur and was shocked when I first saw these buildings surrounded by fences and then being torn down,” wrote one reader in comments on a 2013 blog post by the author on the demolition of the city’s equalization schools.

Equalization schools, facilities built to perpetuate segregated education throughout the South as communities anticipated, and then circumvented, court-ordered desegregation, are among the many types of places designed and built during Jim Crow to impose racial order throughout the South. Unlike monumental sites associated with what Weyeneth described as “connected with the triumph of individual and collective initiative” (p. 41), equalization schools are well outside mainstream America’s popularly held conceptions of Jim Crow for several reasons. They are, as Weyeneth observed, places that force people to confront a disturbing and uncomfortable past. “I Googled for articles to figure out what the heck was going on”, said the same reader in comments to the 2013 blog post. “What little I found did not touch on the historic significance of these buildings.”

I began asking people to tell me where they would take visitors to Decatur to see places associated with black history in the city.2 “There aren’t any left,” replied local preservationists and African American residents. As the city was completing construction of the new civic buildings where Decatur’s black elementary and high schools had once stood, one lifelong African American resident told me that the places she used to bring younger family members and friends are all gone. But, she added, she’d take them to “the new building on Trinity because there you’ll be able to go in there and look at some history.” For her and other black Decaturites, the only place to experience black history will be in exhibits prepared by the city in its new civic building. They and others may be able to see “some history,” but we’ll never be able to touch its cold masonry surfaces or experience its marginalization deep in our souls.

Weyeneth underscored the importance of experiencing historic racialized space beyond reading about segregation in static accounts. Visitors to these historic places include aging survivors from Jim Crow segregation, their younger family members, and people whose only experience with racism is drawn from the arts and the academy. Exposed to daylight and effectively interpreted, the preserved and protected sites from our dark past offer unparalleled educational opportunities. Once these places disappear from the landscape, their power to remind us that racism continues to be a factor that cuts across all American social strata is lost. The headlines from 2014 bear this out, from racial profiling in Decatur to the shooting deaths by police of unarmed black men in Ferguson, Missouri, and New York City.3 Weyeneth quoted a St. Louis man who said that every community should preserve “at lease one site associated with racial segregation in order to remind us that there are two racial universes in the United States” (p. 37).

The architecture of racial segregation was the material culture of an institution, white supremacy, channeled through Jim Crow. The “rules of the game” were the legally sanctioned imposition of isolation and partitioning. Nearly a decade after “The Architecture of Racial Segregation” appeared, Weyeneth reflected on it and his career in his 2014 National Council on Public History Presidential Address [The Public Historian 36, no. 2 (2014): 9-25]. In his essay, Weyeneth wrote about embracing the dark past, “the chapters of history that are difficult, controversial, or problematical.” That dark past, “The Architecture of Racial Segregation” reminds us, persists beyond the twentieth century’s built environment and into how we interact with the past in the present. That, I think, is Weyeneth’s enduring message for historians and preservationists today and fifty years from now.

~ David Rotenstein is a consulting historian based in Silver Spring, Maryland. He researches and writes on historic preservation, industrial history, and gentrification.

Ediitors’ postscript: This essay was completed prior to the Charleston shootings and the nationwide calls to remove monuments and other artifacts associated with segregation and white supremacy.

1 Historic Resource Survey Final Report, September 1, 2009. City of Decatur; Thomas F. King, “Blessed Decatur,” CRM Plus, February 5, 2013

2 David S. Rotenstein, “Decatur’s African American Historic Landscape,” Reflections 10, no. 3 (May 2012): 5–7. Craig Evan Barton, ed., Sites of Memory: Perspectives on Architecture and Race (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001); Ned Kaufman, ed., Place, Race, and Story: Essays on the Past and Future of Historic Preservation (New York: Routledge, 2009); Margaret Ruth Little, “Getting the American Dream for Themselves: Postwar Modern Subdivisions for African Americans in Raleigh, North Carolina,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 19, no. 1 (2012): 73–87; Andrew Wiese, Places of Their Own: African American Suburbanization in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

3 David B. Rivkin Jr. and Andrew Grossman, “Winning Civil Justice for Michael Brown and Eric Garner,” The Washington Post, December 12, 2014; David S. Rotenstein, “A Lesson in Racial Profiling and Historical Relevance” History@Work, April 10, 2014.