Historical thinking and the place of history in public policy development

24 February 2017 – Jean-Pierre Morin

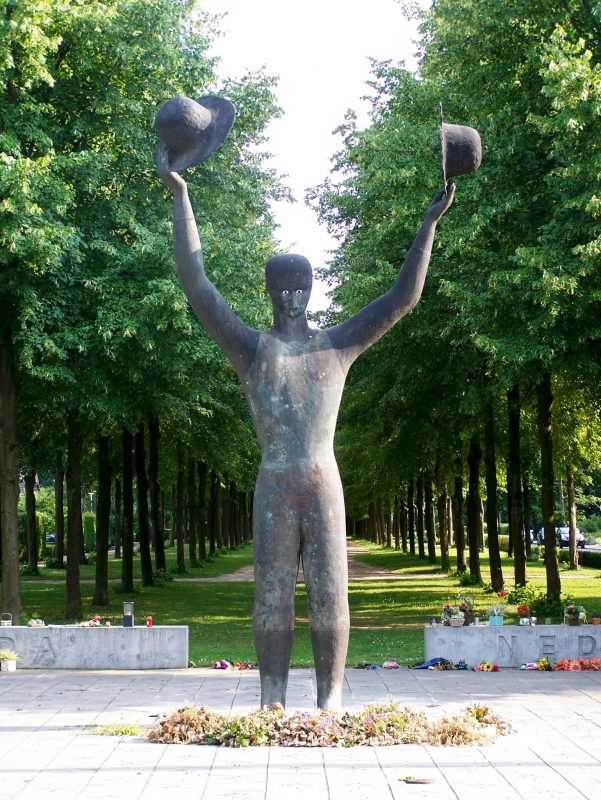

Henk Visch, “Man with Two Hats,” National Canadian Liberation monument, Apeldoorn, the Netherlands. Photo credit: Brbbl

For the past seventeen years, I have worn two hats every day that I’ve gone to work. The first one is my historian hat, as I’m the staff historian for the Canadian department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs where I research the history of the institution, prepare materials for public consumption and answer questions relating to the 260-year history of Canada’s policies towards Indigenous peoples. My second one is my senior policy adviser hat, as I work on policy documents for the Canadian government, drafting briefing materials for senior officials, analyzing political perspectives, and making policy recommendations. From my perspective, both of these hats sit squarely on my head at the same time.

As someone who must wear both the “historian” and the “policy analyst” hats, I’ve come to realize that what I’m doing is applying the historical thinking I’ve learnt through my historical training to the process of policy analysis. This adds value to an often convoluted and complex policy process. For example, when making policy recommendations on the Canadian government’s approach on Indigenous issues, I use historical methods and approaches to provide the best possible contextual information. I aim to use the tools from my “historian’s toolkit,” to borrow from Alix Green, to better organise information, challenge assumptions, and use historical approaches to help fill the information gaps in the policy making process.

Obviously, I’m not the first to note that historical thinking can be valuable to policy making, nor am I the most resent person to comment on it. In the late 1970s, historians, such as Edward Berkowitz in The Public Historian, specifically saw a role for historians in the policy making process due to our training into “historical thinking.” [1] These arguments were embodied in the 1980s with the establishment of the applied history program at Carnegie-Mellon by Peter Stearns and Joel Tarr, who argued the program would allow historians to be better trained to fulfill policy analysis jobs, because “the existing array of mainstream policy disciplines, with economics at the top, have proven inadequate to master the kinds of information and to produce the types of judgments necessary for effective policy in a number of fields.”[2] A comparable program at University of North Carolina under Otis Graham took a different approach and followed the Neustadt and May model of training policy makers themselves in the fundamentals of historical thinking.[3] In the United Kingdom, the growing discussion of “evidence based policy making” since the Blair government helped spur the work of the History and Policy group that strives to create better communication between historians and policy makers. Most recently, Alix Green has argued that historians need to be brought into the policy making process itself so that there is “thinking with History in policy”.[4] The public history community is continuing this discussion not only in classrooms, but also here at History@Work in its new section “The Contested Past.” Few in the historical community would argue that history, both the field and the methodology, doesn’t have a place in the world of policy makers and politicians.

Example of quantitative graphic showing economic sectors. Image credit: Green Economy Coalition

I must admit, however, that my experience merging historical thinking and policy development is not the norm. Despite the fact that historians have long stated that “history matters” in the policy process, my experience has shown that few policy makers feel the same way. It is clear that there is a serious disconnect between how policy analysts view history, and how historians view the role of history in policy making. I’ve seen the policy making process ignore or simply set aside historical research or approaches, in favour of more “hard core” and “quantitative” research (assuming that research was used at all) or used in a limited fashion that is only for context setting but not used in any other part of the policy process. Even in institutions that have staff historians, they play nearly no role in the policy making process. The historical community, well aware of this “dismissal of history,” has been making public statements on why history matters to policy makers, whether that be through the Historians on the Hill series of the National History Center in Washington, D.C. or the seminars organised by the History and Policy group in the United Kingdom. I’ve often felt, looking at the efforts of both sets of colleagues, that historians want to show that they can add to the discussion, such as through the History Relevance Campaign, while policy makers think that all that history is of little use to them.

As I observe the debate about history in public policy development, I often wonder if we are trying to sell policy makers a bag of goods that they don’t want because they don’t understand our sales pitch. At the same time, those policy makers aren’t even looking in our direction, as their eyes are caught by the shiny and sparkly duds of the quantitative fields (such as economics, statistics and political science), whose hawkers are extolling the wonders of “ready-made evidence.” That being said, the “past” is constantly being used by decision and policy makers whether they are aware of it or not. Politicians, senior officials, and public servants all use elements of the past when discussing or considering actions and decisions. Briefing materials and policy documents may have “background” sections, often not based on formal historical research methods. As there is the false belief that “anyone can do history,” even without proper training in historical methods and approaches, policy analysts undertake research that is historical in nature without grounding it in historical methods or without fully understanding historical analysis, building sound arguments, or providing historical context.

Policy makers are not going to stop what they are doing, admit the error of their ways, and turn to fully trained historians simply because we in the field are telling them to do so. We need to prove to them that having someone trained in historical thinking, equipped with the “historian’s toolkit,” would be beneficial to their needs. It isn’t enough for us to say “history matters.” We need to tell them why history matters and how using proper historical methodology will bring about better and more nuanced policy analysis. We need to prove to our policy-making colleagues that “history adds value” to the process because proper historical thinking organizes information in a manner that provides new perspectives and understandings, that it helps policy analysts challenge their assumptions by helping them understand the foundations of their questions, and that the approaches behind historical analysis helps extrapolate gaps in information.

To prove that we can add value to the policy process, we are going to need to adjust our approach in how we speak to policy makers. It isn’t up to us to tell them what they need to know. We need to ask them what information they need and tailor our answers to those needs. We need to establish continuous dialogue between ourselves and policy makers—not just those at the top who make the decisions and sign bills into law, but also the policy analysts toiling in departments, ministries, and agencies who actually do the policy analysis and write the recommendations. To do so, we will need to learn how to produce the documents used by policy makers: the brief, the position paper, the policy report. We aren’t speaking their language, so it’s time for us to start speaking theirs and showing them why history matters.

~ Jean-Pierre Morin is the staff historian at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada and the Public Servant-in-Residence, Carleton University. He is currently working on developing a workshop to help train historians in preparing materials for policy development.

[1] Edward D. Berkowitz, “The Historian as Policy Analyst: The Challenge of HEW,” The Public Historian 1, no. 3 (1979), 19.

[2] Peter Stearns and Joel A. Tarr, ”Applied History: A New-Old Departure,” The History Teacher 14, no. 4 (August 1981), 519.

[3] Otis L. Graham, “Uses and Misuses of History in Policymaking,” The Public Historian 5, no 2 (Spring 1983), 9.

[4] Alix R. Green, History, Policy and Public Purpose: Historians and Historical Thinking in Government (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), 37.