History and performance: Hamilton: An American Musical

23 March 2016 – David Dean

The Public Historian, performance, music, theater, TPH 38.1, "Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton" responses

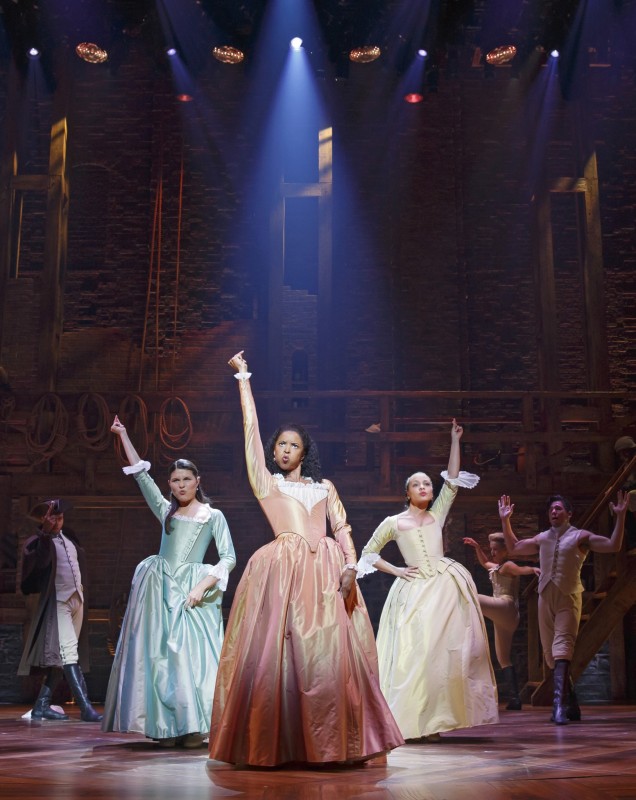

As Alexander Hamilton’s wife, Eliza Schuyler Hamilton, actress Phillipa Soo (left) dances alongside Schuyler’s sisters Angelica (Renée Elise Goldsberry, center) and Peggy (Jasmine Cephas Jones, right). Photo credit: Joan Marcus

Public historians have spent a good deal of time looking at how history is performed in museums and living history sites, in reenactments, and on film and television. Theatre, opera, and musicals have received far less attention, and one reason for this might be that these forms of representation are often thought of as elitist.[1] As Lyra Monteiro points out in her review of Hamilton: An American Musical, the overwhelming majority of audiences for Broadway shows are white (and presumably well-off). This seems particularly ironic, given that Hamilton has been congratulated for challenging dominant white-centred narratives of the American past. My focus here, however, is not to engage with this specific representation of American history. Rather, I would like to briefly explore three points of engagement that public historians might find helpful in thinking about how theatrical performance brings, as Monteiro puts it, “history to life,” namely historical accuracy, ownership of the past, and historical distance.

What do we mean when we talk about bringing “history to life”? Monteiro italicizes the word “history” and rightly so. What she has in mind is what we might call historiography–how the meaning of the past is shaped by our representations of it–and her concern is that in this case, the historical meaning transferred to audiences is an impoverished one.

Bringing the past “to life” also signals a nontraditional form of representation, moving from writing the past to performing the past. When we perform the past, the point driven home by Hayden White some years ago–that the content of our history writing is shaped by the form it takes–becomes very visible.[2] When we perform the past, we strive to entertain as well as educate, to engage as well as inform, and to stimulate the senses as well as enhance understanding. In doing so, we sometimes have to sacrifice historical accuracy.

Monteiro provides an example: an invented tavern scene where historical figures meet who could not have done so. Even Samuel Adams makes a symbolic appearance through the quaffing of the beer (established 1984) named after him.[3] This impossible rendezvous is more than just a dramaturgical device. It also creates historical meaning by allowing Hamilton to side with the radicals rather than his hero, Burr:

Laurens: Burr, the revolution’s imminent. What do you stall for?

Hamilton: If you stand for nothing, Burr, what’ll you fall for?[4]

Does it lay the grounds for a conflict that would culminate in a duel between the two and Hamilton’s death? More generally, audiences, convinced that the heroes of the Revolution were united from the beginning in the face of British tyranny, are witnessing historical actors making difficult and different choices. Playing with time and actualizing the impossible meeting on stage might be historically inaccurate but carries the potential of making useful historiographical arguments.

This scene also features Lafayette (“the Lancelot of the Revolutionary set”). Daveed Diggs, who played this role (as well as Jefferson), speaks of feeling a “sense of ownership over American history.” Like Leslie Odom, Jr. (also quoted in Monteiro’s review), what Diggs experienced in bringing history to life on stage is the past re-imagined and re-performed. For performance studies scholar Richard Schechner, this repeated, “twice behaved” performance means that the past is actualized once again, similarly but differently.[5] In the moment of the musical, the actors are witnesses to, and participants in, the Revolutionary past, and it is this experience that gives them a sense of ownership. Theatre scholar Freddie Rokem has argued that theatrical energies turn actors into “hyper-historians,” thus also enabling audiences to experience the past that has reappeared on stage.[6]

I’m not sure how often the challenges we historians face have been captured in tag lines for theatrical productions, but the claim that Hamilton is a “story of America then, told by America now” speaks to that of historical distance, our negotiations between the past we wish to represent and the present in which we do our work.[7] Not surprisingly, historical representations are shadowed by their creators’ present and sometimes seem to be as much about the present as about the past. Monteiro argues that Hamilton’s story of America then is flawed, and the way it speaks to America now is unsatisfactory.

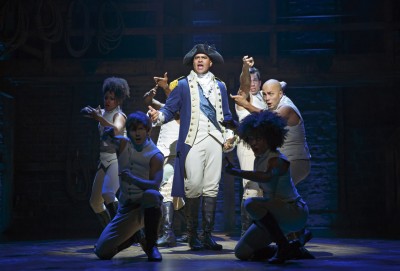

Christopher Jackson as George Washington and the ensemble of Hamilton. Photo credit: Joan Marcus

Certainly we can agree that the stakes are high, and it seems clear that playwright, composer, lyricist, and actor Lin-Manuel Miranda was well aware of this: “History Has Its Eyes on You” sing Washington, Hamilton, and their men.[8] But History, of course, is Janus faced: it looks backwards as well as forwards, and there are many ways of seeing. By invoking the politics of memory, Hamilton invites us to see the past as contested territory. If Odom, Jr. is right, and the show does succeed in giving people of color presence in a past from which they have been excluded, or, I’d add, encourages whites to rethink their own place in history, then perhaps it is because historical distance has been collapsed through rap and hip-hop and the presence of a primarily non-white cast. After all, Eliza and the full company leave us with an important question that is also a warning and an invitation: “Who Tells Your Story?”[9]

[1] David Dean, “Theatre: A Neglected Site of Public History?” The Public Historian 34, no. 3 (Summer 2012): 21–39.

[2] Hayden V. White, The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990).

[3] Annotation by Epaulettes, http://genius.com/7854738.

[4] “Aaron Burr, Sir.” Lyrics: http://genius.com/Lin-manuel-miranda-aaron-burr-sir-lyrics. Song posted by Zoe Grandy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Es1MZO-a4So.

[5] Richard Schechner, Between Theater and Anthropology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), 36.

[6] Freddie Rokem, Performing History: Theatrical Representations of the Past in Contemporary Theatre (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2000), 13.

[7] Michel de Certeau, The Writing of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 23, 35–36; Mark Salber Phillips, On Historical Distance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

[8] “History Has its Eyes on You.” Lyrics: http://genius.com/Lin-manuel-miranda-history-has-its-eyes-on-you-lyrics. Song posted by Zoe Grandy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlpY3gIsfcY.

[9] Italics mine. “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story?” Lyrics: http://genius.com/Lin-manuel-miranda-who-lives-who-dies-who-tells-your-story-lyrics. Song posted by Zoe Grandy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlpY3gIsfcY.

~ David Dean is professor of history at Carleton University, Ottawa, and co-director of the Carleton Centre for Public History. He co-edited History, Memory, Performance (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave, 2015) and blogs at his website.

Editor’s note: In “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton,” published in The Public Historian (38.1), Lyra Monteiro asks, “Is this the history that we most want black and brown youth to connect with–one in which black lives so clearly do not matter?” This is the third of four posts ( first post and second post here) that will be published by The Public Historian responding to Monteiro’s review.