International Family History Workshop, Part I

19 October 2017 – Jerome de Groot and Tanya Evans

methods, family history, public engagement, community history, memory, collaboration, international, genealogy

Alison Light speaks with attendees of the International Family History Workshop. Photo credit: Tanya Evans

The study and practice of family history is fraught with methodological, historiographical, practical, ethical, and cultural concerns for scholars and practitioners alike.[1] In trying to design an event that might respond to and interrogate these concerns, we asked: What new knowledge might be created if we bring scholars together to discuss the phenomenal growth of family history in different nations? The result was the International Family History Workshop held in Manchester, England in September.

The conference sought to address the following questions: Is family history a useful template for public historians? Is it something that can be defined, understood, and studied? How do global systems built for commercial profit but which also facilitate research, investigation, and knowledge gathering—subscription websites and software tools—engage with local practice at a regional, national, city, or town level? Conversely, how does local genealogy engage with the hyperglobalised flow of people, information, and knowledge that we see in the modern world? Is family history a primarily western discourse, or has it (within the academy, within public history scholarship) been given a “centre” weighted around practice in the USA, Europe, and Australia? Does it actively marginalise and create edges, enshrine particular bureaucratic states and colonial gathering of information, support class and gender structures, and ensure the continuing digital divide? Is it fun, emotional, strange, or worrying, and is it practiced and felt the same from São Paolo to Seoul, and from Melbourne to Manchester?[2]

We were also keen to learn more about how social media helps to facilitate family history research and enables collaborations between different communities of researchers across the globe.

Manchester Central Library. Photo credit: Gtosti, CC BY-SA 3.0

Further, we asked what might happen if we sought financial support from one of these major organisations—Ancestry—in terms of research, scholarship, and event development? Might we be able to get towards some kind of working understanding of the phenomenon as it might be studied and discussed, or would we emerge instead with a clear understanding of the diversity and plurality of genealogical culture?

The International Family History Workshop emerged as a one-day conference (with an accompanying special public lecture by Alison Light) in Manchester. We invited scholars from around Europe, from Brazil, India, and Australia to participate, and engaged further with scholars from China, South Korea, and the United States. The event was sponsored by Ancestry.au as part of a developing partnership investigating how family history might be studied and conceived of in the coming years.

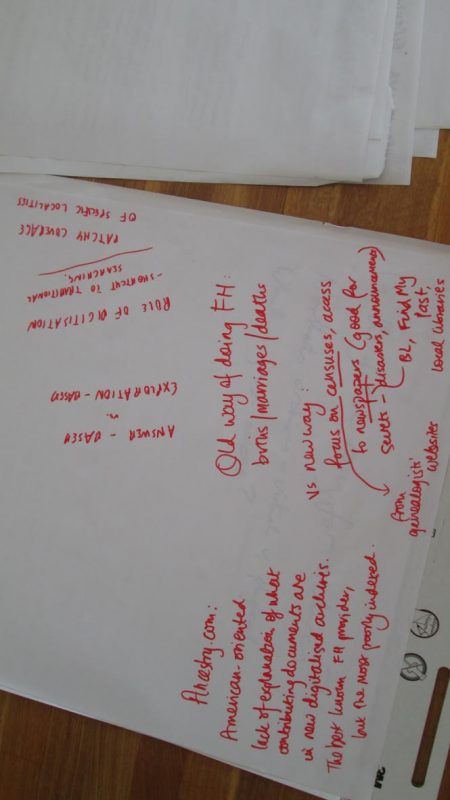

The event was designed carefully to ensure as much public participation and engagement as possible. We had a number of speakers who gave brief presentations. These sessions were followed by small round-table discussions amongst the audience, with posters on the tables to ensure their thoughts were captured (some of these are outlined in our second post on this subject). The point was to ensure that the event was discursive and participatory. Eschewing the style of a classic academic conference, we wanted to explore how we might communicate “scholarly” information and facilitate discussion in an informal yet methodologically useful fashion. This was augmented by the fact that the audience consisted mainly of members of the public rather than academics.

Workshop notes and responses. Photo credit: Jerome de Groot

Ancestry staff members were enthusiastic with their support—helping to design the event and contributing insight into marketing, writing for the public, and communications. They were very interested in the research presented and keen to use this in blogs and social media posts for their various audiences. They were extremely generous with their resources and with advice on how to work with their particular audiences. The partnership and relationship is likely to be of significant lasting value. Nonetheless, the relationship with Ancestry inevitably raised some questions about research ethics. It made us think carefully about the ways that organisations such as international businesses and companies might be considered “research institutions” and partners in development work. To what extent is Ancestry a research organisation, a facilitator of education, or a service? How do users of their websites think about the organisation? How should universities work with businesses, particularly those who provide information and data services? Even those that have been working for some time in this area need to be more reflective about this practice, particularly in the humanities. How should scholars engage with companies to produce future work? How might they negotiate writing collaboratively with non-academic partners and for diverse ends?

The conference raised a final important question for us: How is family history uniquely positioned in the intersection between public, “private,” information, data, research, “history,” and heritage to allow these discussions to arise? Is there something particular about this field that forces us to think in precise ways about such issues? Is this, for instance, something that might challenge “public history” methodologies and existing work on such relationships? Might we have to begin to import ideas from other disciplines such as critical management studies or organisation studies in order to develop models for understanding? The specific ways in which the conference answered some of these questions and raised others will be explored in a second post.

~ Jerome de Groot teaches at the University of Manchester. He is the author of Consuming History (2008/ 2016), The Historical Novel (2009), and Remaking History (2015).

~ Tanya Evans teaches public history at Macquarie University in Sydney Australia where she is Director of the Centre for Applied History and President of the History Council of New South Wales. Her books include Fractured Families: Life on the Margins in Colonial New South Wales (2015), (with Pat Thane), Sinners, Scroungers, Saints: Unmarried Motherhood in Modern England (2012), and Swimming with the Spit (2016). She has worked as a historical consultant for charities in Britain and Australia and for the television series, Who Do You Think You Are?.

[1] See, for instance, Benjamin Filene, “Passionate Histories: ‘Outsider’ History-Makers and What They Teach Us,” The Public Historian 34, no. 1 (2012): 11–33 and Jerome de Groot,“On Genealogy,” The Public Historian 37, no. 3 (2015): 102-127.

[2] Some of these concerns were discussed in responses to de Groot’s article, collected here.