Jack the Ripper Museum

19 November 2015 – Claire Hayward

In August 2015, a museum that had originally been billed as “the first women’s museum in the UK” opened instead as the Jack the Ripper Museum on Cable Street in the East End of London. ‘Jack the Ripper,’ an anonymous figure who murdered and mutilated at least five women in the late nineteenth century, has become the focus of a museum that had once been promised to represent and celebrate untold histories of women.

The unveiling and opening of the museum has caused a great deal of controversy in the United Kingdom because planning permission had been granted for a museum focusing on women’s history. The change of use application for the site explained that the Museum of Women’s History would “analyse the social, political and domestic experience of women from the time of the boom in growth in the East End in the Victorian period through the waves of immigration to the present day.” There is already a museum of women’s history in the UK–the Glasgow Women’s Library in Scotland has been an accredited museum since 2010–but the Museum of Women’s History would have been a valuable addition to London’s public history sites and, furthermore, could have paved the way for improving the representation of women in museums across the UK.

The content and message of the as-built Jack the Ripper Museum has been central to criticism and protests from historians, women’s community groups, and other social campaigners. The logo for the museum initially showed a silhouette of ‘Jack the Ripper’ with a splattering of blood emerging from his feet and walking cane. This logo continues to appear on items in the museum shop, but an updated version on the website does not include the blood splatter. The logo remains, however–a symbol not of women and women’s history but of those who have committed acts of violence against women.

The founder of the museum, Mark Palmer-Edgecumbe (previously head of diversity at Google), has argued that the museum “is absolutely not celebrating the crime of Jack the Ripper but looking at why and how the women got in that situation in the first place.” His defense of the museum is little more than victim blaming and highlights one of the major issues with the Jack the Ripper Museum. The museum, by placing the history of ‘Jack the Ripper’ before the histories of the women he murdered, does little to challenge and deconstruct popular representations of women’s lives, both historical and contemporary.

However, there has been a lively, enthusiastic, and productive response to the museum. A group of volunteers have started raising funds for a proposed East End Women’s History Museum to fulfill the initial aims of what is now the Jack the Ripper Museum: to preserve, record, and represent the diverse women’s history of the East End of London.

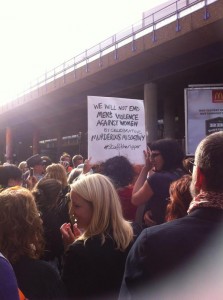

Protests against the Jack the Ripper Museum have gained significant media attention. They have centered on the violence that women face today as well as the inadequate representation of women in public history. One placard at the protest I attended on 4 August read, “We will not end men’s violence against women by celebrating murderous misogyny.” The other side of the placard explained that 76 UK women have been killed by men so far in 2015. The link between past and present highlights an important role of museums in society. Like the Museums Respond to Ferguson discussions in the United States, protests against the Jack the Ripper Museum have shown that museums are political and should respond to contemporary events and society.

I should disclose that I have not been inside the Jack the Ripper Museum, nor do I have any intention of doing so. Reviews from those who have visited have not affirmed Palmer-Edgecumbe’s arguments that women are central to this museum. In a review for the UK’s Museums Association, Nicola Sullivan explained that at the end of her visit, she was “feeling quite sick, not just because of the crude and opportunistic display of violence against women but because of the opportunity that had been squandered.” Historian Fern Riddell’s review also raises serious concerns about the way women are represented. Riddell critiqued the lack of context and history present in the museum, describing it not as a museum but as a “poorly executed shock attraction.” Both Sullivan and Riddell’s reviews highlight the ‘experience’ and ‘entertainment’ aspect that many of London’s ‘Jack the Ripper’ walking tours also focus on. The museum, like the walking tours or The London Dungeon, does not seem to pay much attention to historical context but to story and sensationalism. These tourist attractions have existed in London for years, yet there has been minimal opposition to them. The Jack the Ripper Museum, however, labels itself as a museum, a place where visitors expect historical context, not gory sensationalism. Perhaps if it was called the ‘Jack the Ripper Attraction’ it would not have encountered so much opposition.

The controversy has raised much bigger questions about public history. In particular, what are ‘appropriate’ subjects for museums to display? There is no topic that a museum cannot cover, but it is the approach that matters. It is important that traumatic and difficult pasts (and indeed, presents) are represented and discussed in museums, but it is equally vital that museums approach such subjects with sensitivity, not sensationalism. As historian Julia Laite has argued, it is important that the victims of ‘Jack the Ripper’–Mary Ann ‘Polly’ Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Kelly–are commemorated, not forgotten. They and their lives represent a difficult and traumatic part of women’s history. Sadly, acts of violence against women are not confined to history; women continue to suffer emotional, domestic, and violent abuse at the hands of men. The victims of ‘Jack the Ripper,’ women and Londoners, deserve and need something radically different from what the Jack the Ripper Museum offers.

~Claire Hayward is a PhD candidate at Kingston University, London, UK.

You can sign a petition against the museum on 38 Degrees. You can also read about, and contribute to the development of the East End Women’s Museum.