Collegial questioning: A new forum on history in the US National Park Service (Part 2)

25 November 2013 – editors

Signs at Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, Colorado. Photo credit: howderfamily.com.

Continued from Part 1

~ Seth Bruggeman, Associate Professor of History and Director, Center for Public History, Temple University

I’ve been fortunate to have had several points of contact with the Imperiled Promise report since its release, from attending early conference sessions with its authors to being a conversation facilitator myself and, most recently, speaking about where it may lead the NPS’s history program. From the outset, I’ve worried that the report, like so much grey literature commissioned by the agency, would languish on some forgotten shelf. So far, at least, that is not the case, thanks largely to the authors—especially Marla Miller and Ann Mitchell Whisnant—and others who’ve played a critical role in ensuring an audience for the report.

Who that audience is, however, and how it discusses the report, raises another set of questions. Though they may be occurring, I have not yet witnessed sessions that put NPS insiders in dialogue with park users. Much of our conversation has pivoted on NPS staff and fellow travelers from universities and elsewhere wondering together how the parks might implement the report’s recommendations: How do we confront controversial topics? How do we acknowledge the agency’s imprint on the stories we tell? How do we share authority with the “public?” Until the public has a seat at the table, though, I worry that our answers to these questions will lack essential perspective.

I worry too about our tendency to discuss the report as a collection of individual findings rather than as a comprehensive vision for a new history program. This tendency has resulted, in part, from the practical limitations of conference sessions and busy schedules. Discussants frequently focus on one or two facets of the report that resonate most powerfully with them. And yet what makes the report so important is how clearly it demonstrates—across the sum of its parts—that what the NPS history program needs is not just a series of adjustments but rather a fundamental shift in the habits of mind underlying its core functions. I am encouraged by recent initiatives, such as Lu Ann Jones’ history academies that recognize this facet of the report and will hopefully make it a centerpiece of future conversation.

Despite these concerns, what has impressed me most over the last year or so is how eagerly so many voices have joined in the conversation about the report and what it promises for the future. It is this sense of excitement and direction that, amid ongoing budget reductions and the calamity of congressional politics, may be the report’s greatest gift to an agency that needs advocates more than ever before.

~~~

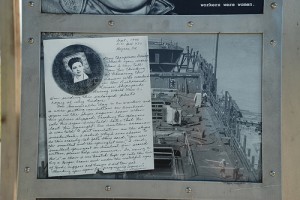

Part of the memorial at Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park, Richmond, California. Photo credit: Russell Mondy.

~ Mary Rizzo, Public Historian in Residence, Rutgers University-Camden

After the opening speakers, we divided up into smaller groups focused on specific topics. Ably led by Christine Arato, the discussion at the table I was at quickly focused on the connection between content and public outreach, or, to boil it down into a somewhat reductive question: is there ever such a thing as universal history? NPS, unlike local historical societies or museums, is in an unenviable position—its parks are supposed to appeal to the broadest group we can imagine: the American people. But, ask any marketer and she will tell you that there is no “general public” but many publics, each of whom should be reached by ever-tighter messaging designed to hail them specifically. ‘Course the NPS isn’t selling soap but something much more emotional, abstract and powerful—the history and places of the national parks.

To its credit, NPS realizes that there are many Americans whom it has not reached and wants to remedy that. Our conversation revolved around the question of how. Does that mean creating special programs and exhibits devoted to particular ethnic or racial groups? Does that mean re-imagining all of our interpretation to include the stories of the previously marginalized? Or is there a universal American story out there that everyone should feel includes them? One of the recommendations of Imperiled Promise seems apt here. The writers argue that in the Park Service there is a “misperception of history as a tightly bounded, single and unchanging ‘accurate’ story, with one true significance, rather than an ongoing discovery process in which narratives change over time as generations develop new questions and concerns and multiple perspectives are explored.” To me, this helps lay to rest the idea of one unchanging history that is going to include everyone in it. History, as a dynamic, living discipline, changes over time. What we ask from our historical sources shifts, as does our interpretations.

Instead, particular stories are the means to connect with audiences. Think about literature. The more particular the story, the better the author is able to give readers access to another world, another time, and other ways of being, which can make it meaningful to diverse groups of people. In grad school, I was a Teaching Assistant for a class on post-colonial gender and sexuality, which was mostly taken by young white Midwesterners. One of the assigned texts was the beautiful novel Cereus Blooms at Night by Shani Mootoo, which tells the story of a transgendered nurse taking care of an old woman who was the victim of horrific childhood abuse living in an imaginary island patterned after Trinidad. What could be farther from the experiences of these students? Yet, they responded emotionally and intellectually to the story, creating empathetic connections to the characters (and learning post-colonial theory in the process). My point, roundabout as it is, is that it is only through particulars that can we create narratives that are meaningful to many. And without the particulars, the universal will likely remain at the level of dull platitude or hollow sentiment.