Mother of invention; or, what my sons taught me about historical reenacting

23 September 2014 – Michelle McClellan

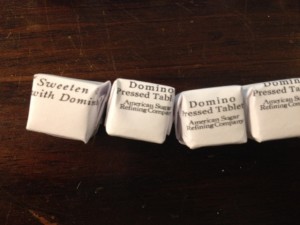

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised when my sons became interested in reenacting. After all, history is the family business–my spouse and I are historians, and our children absorbed a chronological mindset very early. Still, they have often claimed not to like the subject, perhaps because they have heard us discuss our research and teaching until their eyes glaze over. Willingly or not, they have accompanied me on many history-related outings, including an epic road trip following the path of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House” books, complete with overnight camping on the original Ingalls homestead claim. So maybe all of this got into their blood despite their protests. Or maybe they knew that reenacting was the only way their uptight academic parents would let them play with guns.Whatever their motivation, they are now into it, poring over online catalogs of vintage and reproduction gear, participating in online discussion forums, perfecting their impressions, and adopting the lingo. As I helped my older son prepare for a recent outing by individually wrapping 54 sugar cubes (who knew you could find reproduction K-ration labels on

the Internet!), I reflected on the concept of “object-based epistemology” as defined by Steven Conn in his Museums in American Intellectual Life, 1876-1926. Conn argues that late nineteenth-century Americans believed that objects, especially when appropriately arranged in a museum setting, could impart knowledge to any thoughtful observer and that this worldview provided the rationale and intellectual architecture for the museums founded during this period. But after the first quarter of the twentieth century, Conn explains, the rise of specialized disciplines based in ever-expanding universities replaced museums and their collections as centers for the production of knowledge.

When my son returned from his trip (which was three states away), he had lots of stories about the action itself and about the tales he had heard around the campfire. While this was a World War II event, some of the participants reenact other eras as well. One man recounted how, as a neophyte at a Civil War event, he had brought apples, only to be scolded because they were “period-incorrect.” We immediately adopted that phrase into our family lexicon, but it raised larger questions, too. Rather than dismiss the apple critic as an overly enthusiastic crank, I want to understand why he saw the modern apples not just as a mistake but as a threat. This musing brought me back to Conn and to the role of things in connecting us to the past. Maybe object-based epistemology is alive and well (if you’ll pardon the pun) in living history.

Or maybe it’s not quite epistemology that’s going on here–or at least, that’s not the whole story. Conn ends his book with the point that objects still function magically. As someone who has driven thousands of miles to see Ingalls family artifacts, I get it. And if the right objects can facilitate that sublime state known as “period rush,” then the wrong objects–like those apples–can unravel it. I learned that lesson while watching the 1980 film Somewhere in Time over and over on my parents’ VCR when I was a teenager, sinking into fresh despair every time as a modern penny dooms the time-travel love story starring Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour.

I think magic is the right word. And in thinking about all this, my perspective as a parent has been an advantage, helping me to unlearn some biases I absorbed in graduate school and to reconnect with my inner “bonnethead” (as devoted “Little House” fans are known).

As a capital “H” Historian in an academic setting, I once would have dismissed activities like wrapping the sugar cubes or tinting photographs to look older as messy and suspect attempts to blur past and present. But now I can appreciate the creativity and dedication involved. My son and his friends are learning in very self-directed ways, and not just about history, but about teamwork, patience, saving toward a long-term goal (this can be a very expensive hobby), and about how to interact with others of very different ages and backgrounds. I’ve served on enough museum and historical society boards to be struck by the youthfulness of many reenactors, and the participants my son has met have been unfailingly generous in sharing insights and loaning gear to a middle-schooler.

I have also rethought some aspects of teaching. My kids’ absorption in this hobby evokes for me their preschool years, when they learned by doing, by touching, by moving their bodies through space. Why do we take those options away and expect our students to learn while sitting still in classrooms? Doing history is an intellectual exercise, yes, but it is also emotional, kinetic, collective, even spiritual. Role playing, handling objects from the past, dressing up in a corset and hoop skirt and feeling how one’s movements would be constrained–all of these can help us convey the texture of the past, as well as the excitement of studying it, to our students. As Conn suggests, there is a kind of literacy associated with objects. In our increasingly digital age, it is well worth our time to ask our students to learn from the material realm.

As a scholar, I am embarrassed to admit how long it took me to realize the richness of existing historiography in this area. Much recent scholarship has been produced by anthropologists (Petra Tjitske Kalshoven, Cathy Stanton, Jenny Thompson), cultural theorists (Giuseppina D’Oro), experts in performance studies (Scott Magelssen), historians, (Stephen Gapps, Edward Linenthal, Amy M. Tyson), and others (like journalist Tony Horwitz), and it has yielded profound insights on how reenactment practices create identities and serve social, political, and even emotional needs in the present. I call on more historians to add to this literature because reenactors are also making historical knowledge as they choose episodes and themes from the past as especially compelling. We must take this dynamic seriously if we want to understand who cares about history and why, and to make a case for our relevance both within and beyond the academy.

~ Michelle McClellan is Assistant Professor in the Department of History and the Residential College at the University of Michigan.

![Author's son posing in newly acquired World War II uniform and gear. [Posted with Permission.]](https://ncph.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Reenacting-Impression-300x225.jpeg)

Michelle:

I was once a lonely history geek, not raised by historian parents, but by parents to indulged my love for history. They bought be books, they took me to museums, and on vacations we visited National Parks, mainly because I was the one who looked stuff up and wanted to see it.

But one of the best things they did was allow me to get into Civil War reenacting, something I did from about 13-21(ish). This was my first experience with *touching* history in a very visceral way.

I understand why our field–academic and public historians as well as history museum professionals–pooh-poohs reenactors. Their single-minded focus and attention to detail can be somewhat overwhelming (and often off-putting) to those of us taught to have a bit of casual remove from the discipline.

But they bring a unique, and frankly passionate, take on history that we would be wise to pay a bit more attention to rather than just be cynical about it.

So kudos for encouraging your sons’ participation in reenacting. Whether they’re pursuing history because of, or in spite of, their upbringing–they’re involving themselves in it, and will be all the better for it.

My $0.02.

Bob, thank you so much for this thoughtful comment, which I appreciate as a historian and also as a parent! I was struck by your phrase, “those of us taught to have a bit of casual remove from the discipline.” I that’s it exactly — and that remove is necessary at times, and an important part of professionalization, but still, sometimes comes with a high price.