NCPH 2013 Student Project Award: Learning from community

10 April 2013 – editors

education, NCPH, graduate students, preservation, NCPH 2013 Awards, projects, public engagement, community history, memory, sense of place, museums, scholarship

The congregation of Cedar Grove Baptist, one of the two churches in Terra Cotta, in the 1930s

Photo courtesy Dennis Waddell.

Editors’ Note: This series showcases the winners of the National Council on Public History’s annual awards for the best new work in the field. Today’s post is by Ellen Kuhn, Shawna Prather, and Ashley Wyatt, students at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and co-creators of the exhibit “Past the Pipes: Stories of the Terra Cotta Community,” which won the 2013 Student Project Award.

What creates a community?

In the face of significant social and economic constraints, a tightly-knit, self-reliant community developed in Terra Cotta, a segregated company town located a few miles west of downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. From the 1900s to the 1970s, members of this community worked at the nearby Pomona Terra Cotta Company, manufacturing clay pipes used to build sewer systems. Terra Cotta was the kind of place where family meant more than just blood kin; it meant giving food to the homeless man who lived in the woods nearby–even though residents had to feed their own large families on less than eleven dollars a week. It meant sharing one church building between Baptist and Methodist congregations, alternating services each week. It meant welcoming white children to play in their homes when a reciprocal invitation to play at white homes was never extended. Today, community in Terra Cotta means keeping bonds initially formed in the neighborhood alive through shared memories.

Now, these previously unheard voices are featured at the Terra Cotta Heritage Museum in a permanent exhibition that was created through a collaboration known as the Terra Cotta Community History Project. Under the direction of Dennis Waddell, head of the Terra Cotta Heritage Foundation, and Benjamin Filene, director of the public history program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), we–eight graduate students in UNCG’s public history program–worked closely with Terra Cotta residents to document, preserve, contextualize, and share the vibrant stories of this community.

The Terra Cotta Community History Project unfolded in several phases throughout 2011-2012. We recorded oral history interviews and performed public records research; applied for and received a North Carolina Humanities Council grant; conducted community programming and evaluation meetings; engaged the help of scholarly advisors and a professional exhibition designer; and completely repainted the 70-year old home in Terra Cotta where the museum is located, to name just a few of the steps involved. In each of these tasks, we continually worked to gain the trust of Terra Cotta members and to carefully negotiate the potential tensions between community memories and historical interpretation.

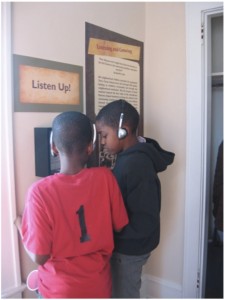

When visitors enter the exhibition “Past the Pipes: Stories of the Terra Cotta Community,” they are also entering a home that was part of the original Terra Cotta community. As they move throughout the exhibition, which occupies three rooms of the original house, we have attempted to engage them with the question of what makes a community by exploring the multiple ways Terra Cotta residents built theirs: family, church, recreation, school, work, and, finally, memory, former residents’ efforts to document and keep alive this once vibrant community. Each section of the exhibition is brought to life through the use of audio clips from oral histories conducted with original community members, quotations that run across the walls, historic community photos, objects donated by the community—including a few pieces of the Terra Cotta pipe manufactured in the factory. Several interactives encourage visitors to leave their mark on the exhibition, including coloring sheets where they can create a historic marker for their own communities.

The Terra Cotta Heritage Museum before and after the installation of Past the Pipes

Photos courtesy Ellen Kuhn

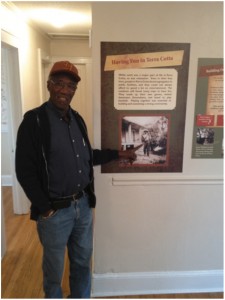

At the exhibition opening in December 2012, we were thrilled to see residents, their families, and members of the greater Greensboro community explore the new exhibition. Former Terra Cotta residents were excited to find photographs of themselves prominently displayed in the museum, reinforcing that their experience was an important part of history. Their descendants encountered familiar family stories while new ones were shared on the spot. Residents of greater Greensboro expressed surprise that they had never heard of this community and delight that its history was being shared.

Visitors at the exhibition opening explore a “memory map” of the neighborhood and listen to audio clips of oral histories

Photos courtesy Benjamin Filene and Ellen Kuhn

Our coursework has provided a fundamental grounding in public history, but immersing ourselves in a project the size of the Terra Cotta Community History Project allowed us to experience firsthand the challenges presented by publicly engaged historical work. When working on a “memory map”–a contemporary map of the area on which residents were encouraged to write or draw their memories of the vanished neighborhood–and listening to oral histories, we learned that memory is a tricky thing and that different people remember events and places in different ways. We learned to embrace the power and resilience of identity–residents have an overwhelmingly positive recollection of their lives in the neighborhood. We learned that navigating through a community we were not a part of takes time and that trust-building and dedication are two of the most important parts of a public historian’s work.

In the end, this project brought home to us the joys and rewards of public history. The reactions of the visitors at the exhibition opening, both former and current residents and members of the wider Greensboro community, were truly fulfilling. We took pictures of a man who was excited to find himself in two photos in the exhibit. After he posed for his picture he whispered to us that of all his family members in one photo, he was the only one left living. With the aging population of the Terra Cotta community, we knew that some of these stories were close to being lost forever, and this man’s comments reinforced the importance of the work we were doing. We helped preserve their stories for both their descendants and the future residents of the Greensboro area.

Public history is challenging. Public history is emotional. Most of all, public history is important and valuable, and this project helped us to see the power of good public work. We will carry the passion this project instilled in us forward into our careers.

~ Ellen Kuhn, Shawna Prather, and Ashley Wyatt

Excellent project. Way to go UNCG.

What a wonderful description of the project! I particularly appreciated the thoughtfulness you have shown about the personal meanings of history. Congratulations!

~Anne

To have dedicated yourselves to exploring deeply beyond nostalgia, and to have discovered the vitality and complexity of this community re-confirms the fascinating privilege and rich outcome of historical research. Congratulations to all on this fine, extensive work.