Outside academe

25 May 2016 – James F. Brooks

Editor’s note: We publish TPH editor James Brooks’s introduction to the May 2016 issue of The Public Historian. This digital version of the piece differs slightly from the print edition. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members.

At our recent National Council on Public History conference in Baltimore, Maryland, attendees had multiple opportunities to explore the intersection of race, racism, deindustrialization, and public history in close quarters–as well as beyond the confines of the conference hotel. Barely one year after the April uprising that followed the death of twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray while in police custody–his spine severed during a “rough ride”–participants toured the east Baltimore neighborhood where the urban rage found its greatest expression. Local leadership activists guided these tours, and we saw the “hidden” Baltimore that lies beyond the Inner Harbor and Camden Yards. A fractured urban fabric of vacant lots, punctuated with the occasional standing, and vital, “brick and beam” shops, apartments, and neighborhood centers that house and serve the residents.

At our recent National Council on Public History conference in Baltimore, Maryland, attendees had multiple opportunities to explore the intersection of race, racism, deindustrialization, and public history in close quarters–as well as beyond the confines of the conference hotel. Barely one year after the April uprising that followed the death of twenty-five-year-old Freddie Gray while in police custody–his spine severed during a “rough ride”–participants toured the east Baltimore neighborhood where the urban rage found its greatest expression. Local leadership activists guided these tours, and we saw the “hidden” Baltimore that lies beyond the Inner Harbor and Camden Yards. A fractured urban fabric of vacant lots, punctuated with the occasional standing, and vital, “brick and beam” shops, apartments, and neighborhood centers that house and serve the residents.

One evening saw us at Ebenezer AME Church (established in 1845, and once a stop on the Underground Railroad) for a community conversation around the misrepresentations in national media that shaped the uprising as racialized “riots” that endangered lives and property. Community speakers ranged from veterans of the 1968 unrest, minister Devon Wilford-Said, and philosophy professor Robert Birt, to activist Paulo Gregory Harrs and photographers Devin Allen and J. M. Giordano, who were directly engaged in chronicling the resistance of last April. Their combined efforts provided the audience a diachronic sense of the history of inequality in Baltimore, from images to experiences to collective response. Notable among the speakers was Allen, a creative and charming self-taught photographer who had only begun chronicling neighborhood life with his camera in 2013–and who, it turned out, became one of only a handful of amateur photographers ever to make the cover of Time magazine.”

My own experience was shaped by these conversations and extended the next day with an outing to “rephotograph” the site of the 1968 “riot” and arson on Lombard Avenue, where the world saw flames leaping up the façade and toward the signage of Attman’s Deli. The deli remains today, isolated in a two-unit building amid an otherwise empty block, ironic evidence for its centrality in the local community as well as the patchwork emptiness of a deindustrialized and partially depopulated city. Counter help and clientele alike were themselves a patchwork of white, black, and multiracial working-class men and women, jovial and edgy amid the frantic lunch hour. The hot pastrami was superb.

This rich “outside” experience served as reminder that public history takes shape as much, or more, beyond the bounds of academic institutions as it does in lecture halls or seminar rooms. This May issue of The Public Historian reinforces that vital fact. Our three featured essays are each positioned in nonacademic settings. Philip Seitz’s “History Matters” recounts the experience of black ex-offenders in Philadelphia who participated in a series of workshops with leading African American historians of slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow to weave the traumas of the past–and present–into a curriculum fabric that promotes behavioral and emotional capacity building in the context of life skills. (Click here for a History@Work post about this project.) Guided by local members of Reconstruction Inc.–themselves veterans of violence and incarceration–the program employed a trauma recovery model to shape the learning and healing experience, as well as a storyteller to help verbalize the past and present. Seitz goes beyond program details to offer trenchant observations from the project’s assessment tools, with results that showed the immediate and painful impact of confronting a history of violence and racism could, in at least some cases, “turn down the rage [and] use it as a flame.”

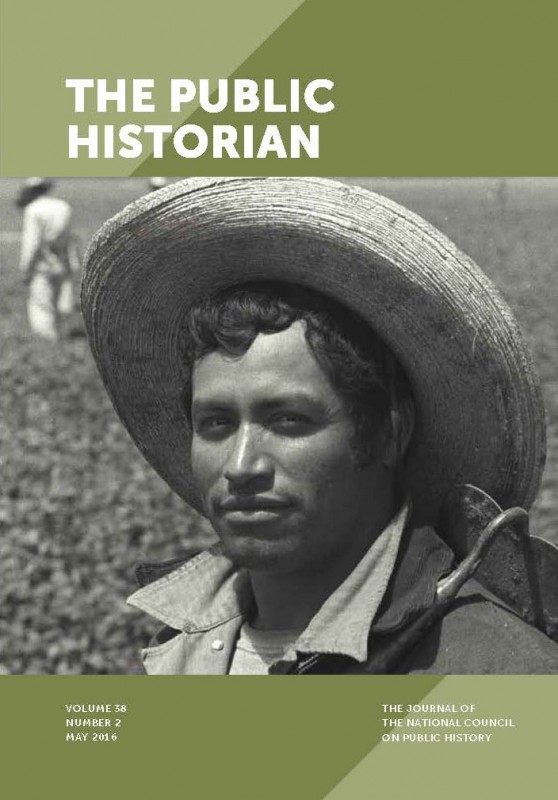

Mireya Loza’s “From Ephemeral to Enduring: The Politics of Recording and Exhibiting Bracero Memory” takes us from Philadelphia to Washington, DC, to explore an ambitious oral history program at the National Museum of American History. That five-year project culminated in the exhibit Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program, 1942–1964. Loza served as principal investigator for the collection of more than eight hundred oral histories and hundreds of digitized documents that underlay and informed the exhibit. This was much more than a collecting and archiving project, however, since the work of Loza, her colleagues, and students intersected with intensification of national debate about “guest worker” status that former president George W. Bush had initiated in 2004. Thus, “political conversations about the contemporary use of guest workers collided with the historical memory produced by bracero communities,” especially as the Bracero Justice Movement sought to recoup an estimated $32 million in back wages that braceros lost in a jointly sponsored US-Mexico program that withheld 10 percent of each workers’ paycheck, to be given back once workers returned home. Visitor experience also proved mixed. Many exit comments suggested that the exhibit was viewed through the filter of contemporary politics, and few understood that braceros were not permanent “immigrants,” and some visitors understood the exhibit to be an endorsement by NMAH of “illegals” in the United States. Bittersweet Harvest confirms that public history is always a dialogue between past and present, one whose content is as much a matter of the viewers’ experience as it is the curator’s intent.

The unpredictable nature of public response to historical representation and commemoration is further highlighted in Tonya Davidson’s exploration of interactions with Canada’s National War Memorial in Ottawa. Each of her four cases–ranging from regular (if prohibited) use of Confederation Square, which hosts the National War Memorial, for skateboarding, to an instance of public urination, as well as formally sanctioned expansion of commemorative activities of the National War Memorial in remembering Canada’s WWI sacrifices, intensified in 2008 through the kinetic light installation of the “Vigil Project” and the 2006 “Valiants Memorial” to fourteen key figures in Canada’s military history–display the “pedagogic possibilities” of public history installations. The richest irony, perhaps, lies in the fact that the most public “abusers” of the NWM–skateboarders who delight in the challenges of riding the rises and slants of the mica-rich granite–are precisely the same age demographic that the memorial seeks to honor in an earlier generation. Although older generations of Canadian citizenry rose in voluntary patrols to keep “skaters” at bay, the “learning from” aspects of this experience may remind visitors that the young men (and women) who sailed to Europe between 1914 and 1918 were driven as much by desire for adventure and personal challenge as they were grand patriotism. Davidson’s analysis suggests again that the “multiple types of learning” that unfold in public history are shaped by the agency of the public(s) equally with those who design the products. All of us at TPH are grateful for the work of the local arrangements committee, Denise Meringolo, Elizabeth Nix, Glenn Johnston, and Susan Philpott, and look forward to our next experience “outside” the academy at Indianapolis next year.

~ James Brooks is editor of The Public Historian and professor of history and anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.