Practice, in place

29 August 2016 – James F. Brooks

Editor’s note: We publish TPH editor James Brooks’s introduction to the August 2016 issue of The Public Historian. This digital version of the piece differs slightly from the print edition. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members.

Editor’s note: We publish TPH editor James Brooks’s introduction to the August 2016 issue of The Public Historian. This digital version of the piece differs slightly from the print edition. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members.

“Oh no. Not law school. Do something useful with your life.” These words, spoken by New Mexico Senator Pete Domenici to our immediate NCPH past-president Patrick K. Moore during a stint as a young legislative intern in Washington, DC, provide a point of entry into this issue of The Public Historian. Quoted in his presidential address in Baltimore this past March, “Places, Privilege, and Public History: A Journey of Acknowledging Contested Space,” the senator’s admonition underlies Moore’s engaging personal reflections on how a boy raised in the sealed-off world of the Los Alamos National Laboratory became an impassioned advocate of “doing” history at the local and community level. Honing his “practice in place” led to personal and professional awakenings that many of us in the public history sector have likewise experienced. “As I began to probe the deeper–and often uncomfortable–questions surrounding historic places and events,” he writes, “I often found myself asking ‘which story is right? Or more importantly, how would it be possible to allow very different perspectives to overlap?’”

Moore’s notion of “contested space” is grappled with by the full range of articles and reports from the field in our August issue. We are delighted that, at the request of our editorial office, past NCPH president Bob Weyeneth and Daniel J. Vivian worked together to author a pointed and insightful essay on the state of public history programs today, and the perils that lie ahead as dozens of colleges and universities leap toward public history as “the new black” in humanities education. We at UC Santa Barbara, the department that established the discipline in 1976, have grown increasingly uneasy with the proliferation of programs that seem–not always, but often–to be aimed as much at generating tuition revenue as developing new professionals for a field that, while dynamic, is hardly a solution to chronic underemployment in the academy and allied enterprises. Their essay offers professional insights from Weyeneth’s distinguished University of South Carolina public history program and Vivian’s experience in the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, as well as his directorship of the public history program at the University of Louisville. Observing the NCPH’s own explosive growth over the last decade, “Charting a Course: Challenges in Public History Education, Guidance for Developing Strong Public History Programs” lays out three components for the future–the building blocks essential for a public history program, the motivations that inspired the NCPH to develop a comprehensive “best practices” document in recent years, and that report in its entirety under the authorship of Vivian and Jon Hunner of New Mexico State University. We agree with Weyeneth’s assessment that “the fundamental issue that underpins current concerns is quality: in programs old and new, big and small.” The very fact of the collaborative effort in this essay speaks to the professionalism and commitment of its authors.

In keeping with our “Practice” focus, we offer two Reports from the Field that likewise emphasize methods, professionalism, and the importance of place. Erin Conlin’s report on meaningfulness and manageability in community-based oral history projects cautions that enthusiasm alone cannot guarantee success. Drawing upon extensive experience with the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida, Conlin argues that this is especially the case in establishing the early phases of a project, where practices and parameters must be made clear to practitioners and narrators alike. Oral history solicitation and collection often involves students from relatively secure socioeconomic locations engaged with narrators whose experience embraces more precarious lives, and unless clear benefits to the community are evident, interviews and archives may be seen as much an exploitation as a contribution. Alliance in advance with community leaders, and guidance toward good listening, reflection, and thoughtful questioning are essential to success.

Conlin’s Florida-based project insights are followed by a far distant, and pathbreaking, exploration of public history training in China, co-authored by Na Li and Martha A. Sandweiss. Over nearly two weeks in July 2014, and involving sixteen participating Chinese faculty and a cohort of nineteen faculty, staff, and student visitors from Princeton University, discussion and debate rapidly moved from “best practices” to substantial tensions between the “esoteric” and isolating elitism of archive-based academic history and the “marketplace” qualities of public consumption of historical places and products. The essay includes a discussion of a joint visit to the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, a wrenching experience for those unwilling to accept its “univocal and simplified” representation of the “evil Japanese.” Displays featuring the actual bones of the dead represented “forensic evidence” for the Chinese visitors, while they indicated “disrespect for the dead” to the Americans. If historic awareness and perspective are “transferable skills,” they are also “deeply local and historically specific.” As Sandweiss points out in her concluding thoughts, “public history [in the United States] is a messy process: loud, contested, and contentious.” Such open exchange and conflict is simply not possible in contemporary China, and so how then can the very essence of what we historians practice–the production of knowledge through rigorous interpretation–be demonstrated in the Chinese settings? “For many of the American seminar participants,” she writes, “the very meaning of public history in China seemed an uncertain thing.”

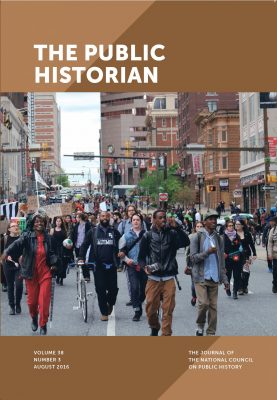

Clearly, we need always to attend to practice, in place, as we seek to strengthen our profession and extend it to histories that have yet to come under its embrace. We see Moore’s call brought to life in our special section, “Baltimore Reviews,” in which Kaitlin Holt, Lauren Safranek, Angela Sirna, Jodi Skipper, Robert Wolff, Françoise Bonnell, Michelle Antenesse, and Vanessa Camacho offer their thoughts on an array of historic sites, tours, and digital media that enriched our experience at the annual meeting. Thanks to each for crafting these “in real time” so that we could publish them herewith. Highlighting this special section is our cover, featuring an image from the Preserve The Baltimore Uprising 2015 Archive Project, a digital repository that seeks to preserve and make accessible original content that was captured and created by individual community members, grassroots organizations, and witnesses to the protests of last year (http://baltimoreuprising2015.org/home). We hope you’ll prosper as much from this entire issue as have we in bringing it to publication.

~ James Brooks is editor of The Public Historian and professor of history and anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.