Preserve historic properties by selling them

12 July 2013 – Bruce Harvey

We’ve all no doubt heard the line thrown back at us: “If you preservationists don’t want this building torn down, then why aren’t you putting your own money into it? How dare you tell a private owner that he can’t tear it down?” A quick keyword search for “preservationists” in my local newspaper provides examples aplenty of variants on these questions.

While they are ultimately wrong-headed, these questions point to some basic truths. First, taking appropriate steps before a proposed demolition enters the planning phase will have a better chance of success than trying to halt a demolition once the permit has been issued. As preservationists, we need to look forward, to help individuals, businesses, and municipalities find ways to protect historically significant buildings. Second, individuals and groups with “skin in the game” are more likely to maintain a building, even if not always in adherence to the standards of historical integrity, and thus prevent the deterioration that often prompts calls for demolition in the first place. Successful preservation requires working collaboratively to identify potential stewards of historic properties and then providing them with the tools and incentives to act on behalf of preservation.

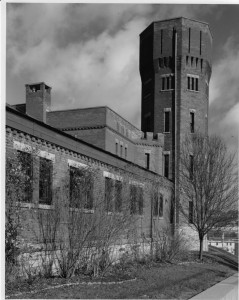

Burritt Mansion. Photo courtesy Bruce Harvey

As a historian and photographer, my capacity to lend brick-and-mortar advice is decidedly limited. I can change light bulbs reasonably well, and I know the difference between 1890s and 1990s window types, but beyond that, I’m not really to be trusted on rehabilitation issues. However, I’ve recently had the chance to become involved in efforts to find good stewards of historic properties from a source that I hadn’t anticipated: the real estate industry. This collaboration has the potential to be a fruitful one for both the cause of preservation of historic buildings and my consulting practice.

An important part of my work as a consultant is the documentation of significant historic resources according to the standards of the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER). Formally trained as a historian, I am also an experienced large-format photographer—a combination that is particularly well-suited to HABS/HAER work. I enjoy these projects, as they allow me to spend intensive and intimate time with remarkable buildings and structures. In such cases, I have provided these buildings with a dignified farewell, a process that is required of the owner as a condition of obtaining the demolition permit, with the documentation materials curated in a public archive. .

It is bittersweet, though, when my work is associated with the removal of significant historic artifacts. It is even more painful, knowing that the vast majority of historic buildings simply disappear without anyone noticing. Seeking ways to use my documentation skills as historian and photographer to prevent the loss of significant cultural resources, I recently developed a professional relationship that holds promise in helping me achieve this objective.

Mike Franklin is a Syracuse-based realtor with Select Sotheby’s International Realty who focuses his efforts almost exclusively on representing the sellers of large, often unusual historic properties that don’t fit into the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) framework that is the marketing standard for the industry. He has relatively wide latitude in marketing these properties; his approach includes creating individualized Web sites. With a background in information technology, Mike got into real estate by working with Paul Malo, one of the pioneer preservationists in upstate New York. Paul’s many passions included finding buyers who would preserve the grand estates that were languishing in New York’s Thousand Islands region. Mike created Web sites that Paul used to attract buyers to these properties. Recognizing that traditional realtors generally have an understanding of neither how to market these “white elephants” nor who might be interested in buying them, Mike moved into the niche on a full-time basis, finding a home with Sotheby’s.

Mike’s job, of course, is to sell real estate. While large, historic properties may be interesting to look at, they often come with huge liabilities. And so selling in this niche is tricky. Yet successful selling is absolutely crucial to the preservation process, as an unoccupied building quickly becomes a public target for demolition.

Mike knew about my documentation work, and saw that my large-format black and white photographs would lend a distinctive, historic look and feel to his Web-based marketing. At the same time, he recognized that historically based copy would provide depth and seriousness to his promotional materials. In the fall of 2012, we launched our collaboration with two self-funded pilot projects (that is, two properties that he had listed without negotiating my costs with the sellers). Our purpose was to develop a portfolio that he might present to potential sellers.

One property was the Burritt Mansion, an immaculate Italianate/Queen Anne house built in 1876 in a small farming community near Syracuse.

The other was the National Guard Armory in Amsterdam, New York. Built in 1895, it is now a private residence and B&B.

A hard truth buried in the accusatory questions that I used to introduce this post is that rehabilitating and maintaining historic buildings requires money, often gobs of it. Most of us who work in preservation don’t have the kind of funds that it takes to realize such a project. But we can leverage the skills that we do have: telling convincing and true stories about the past and, in my case, taking photographs that look “historic,” to attract buyers with the means to maintain these buildings, thereby preserving community culture and memory.

By facilitating continuous ownership, this collaborative approach holds promise for realizing preservation goals. To be sure, a new owner has no contractual obligation to treat the building in accordance with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. And so he or she might renovate the interior or replace the windows without regard for historical integrity. Yet a buyer who shells out a million dollars or more on the purchase price will, in all likelihood, keep the property in good repair and prevent it from becoming a candidate for demolition.

It remains too early to tell how successful a venture this new path will prove to be for me as a consultant. It does not fit well with the MLS marketing approach and time-to-close that many sellers expect. I also can’t assume that sellers will appreciate the value of the additional services that I provide, and thus will agree to a marketing budget that includes my services. Yet, not only is an agent looking to sell a house, he or she is looking to sell a marketing approach to the seller. And so collaboration has been mutually beneficial. It has enhanced my value as a historian. At the same time, my textual and photographic materials have enabled Mike to receive quite a lot of visibility for the former Amsterdam National Guard Armory in particular, and the property recently sold, less than a year from when he took the listing. Our hope is that the successful sale of this property in a relatively short period of time will persuade sellers of other historic properties to appreciate the added value of our approach. My collaboration with Mike has opened the door for me to apply my skills as a historical consultant in a new way. More generally, it shows how historical consultants can claim a stake in the real estate market for historic properties. I would be interested to hear the stories of other historians who have worked at the intersection of real estate and historic preservation.

~ Bruce G. Harvey, Harvey Research and Consulting, Syracuse, NY

I’m delighted to say that I had the chance to team with Mike Franklin again on another fantastic historic house, the Emma Flower Taylor Mansion in Watertown, NY. It is a Queen Anne-ish brownstone pile that was built in 1896, and converted to apartments in 1940 with nearly no loss of architectural details. Lamb & Rich did the design, and, apparently, were tasked with sparing no expense. It is a fascinating house, and the current owners have done a great job to keep it in good condition.

very good initiative, we must preserve historic properties, should never be demolished

Help us in Kerens Texas

I have a 1908 Andrew Carnegie Library listed in Conneaut for $125,000.

Do you have a list of interested buyers of this type of property? Please call with and information or help you can provide me. This is my Home Town and I don’t want this to be “wrecking balled”

That you for your help.

Gary A. Pape