Responding to Baltimore: A role for public historians? (Part 2)

21 May 2015 – Linda Shopes

Editors’ Note: Readers can find Part 1 here. This post continues a short list of what history, public and otherwise, as well as allied disciplines, can do in the face of events like those that have engulfed Baltimore.

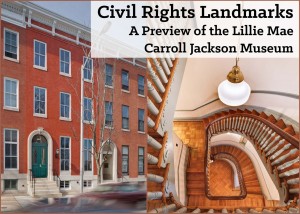

Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson Museum, 1320 Eutaw Place, Baltimore. Restored by Morgan State University. Photo credit: Baltimore Heritage

Third, beyond documentation, history can support change in the present. History is rarely a direct catalyst for change–that comes from social movements. But it can be part of a public conversation that brings attention to the need for change, and it can serve as a means of empowering change-makers. The work of historians and our disciplinary allies can also inform policy, but we must research topics that are relevant to contemporary concerns and present our research in accessible ways. Public historians are at the forefront of these practices.

Certainly the work of local and regional preservation organizations has brought positive attention to sites and stories of Baltimore’s African American communities, including on the West Side where recent disturbances occurred, although it is not clear how effective this can be in reversing disinvestment in these communities in the face of the juggernaut of upscale redevelopment. Likewise, I am heartened by Morgan State University’s efforts to restore the home of local civil rights leader Lillie Carroll Jackson, whose decades-long career as an activist can serve as both inspiration and cautionary tale. Restoration of her home in a historically black neighborhood also suggests the long history of racial segregation in the city.

Oral history, because it involves face-to-face relationships, allows for reflection. Moreover, because it has an affective dimension, oral history can be an especially useful tool in support of change. In the spirit of public history as a “safe space” for considering differences, one can imagine a series of public programs grounded in oral history that gives people the chance to speak and listen to diverse voices and points of view about protest, policing, the criminal justice system, and structural inequalities.

But to be more than preaching to the converted, these programs need broad civic buy-in, the cultivation of relationships over the long term, and wide promotion. Equally important, I believe, are modest expectations. Talk, after all, is just that. These are questions that Baltimore ’68 wrestled with fruitfully, as discussed in The Public Historian.

And for me programs like this always raise questions: Now what? Are all points of view equally defensible? Doesn’t deeper change demand a more pointed critique? Considering these questions, Dan Kerr’s recent History@Work post suggests ways oral and public history can be more directly allied with an activist agenda, working over the long haul with a specific group or constituency to raise critical consciousness and in Alessandro Portelli’s resonant phrase, “amplify the voice” of those seeking justice. Groundswell: Oral History for Social Change provides a forum for practitioners interested in using oral history to support movement-building and transformative social change. It’s too soon to tell, but perhaps there are emerging platforms or existing initiatives that might support something like this in Baltimore.

Finally, public history projects and institutions can provide opportunities for shelter and respite and for reflection during difficult times. Regrettably, some museums–perhaps for reasons of which I am unaware–chose to close during those tumultuous days following Freddie Gray’s death. But one of the heroes of the last couple of weeks has been the Enoch Pratt Free Library, which remained open throughout the disturbances–including the branch in the immediate neighborhood of the most disruptive protests–and welcomed young people during the time schools were closed. Some cultural institutions extended a special welcome to local people troubled and stressed by current events, staying open and even offering free events.

Reflecting a high degree of organization within the city’s cultural community, it was easy to find out how cultural organizations were responding to the crisis via the weekly e-newsletter of the Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance. While there are relationships, networks, and events that bring the Baltimore public history community together, we lack a similar hub that could promote and advocate for our interests.

But I’d like to suggest a less concrete value of our work, too. As it turns out, just as Baltimoreans were protesting Gray’s death, I was reviewing contemporary reports of the ‘68 disturbances on the Baltimore ’68 website. While I know real gains have been made, reading these materials, I could not help but conclude that little has changed in this city. Deep, structural racial divisions, multiple grievances by black citizens, police misconduct, ineffective civic leadership, and inflammatory rhetoric by those who should know better remain. Indeed, one might speak of the progress of inequality in Baltimore.

Then a few days later, I viewed two exhibits at the Maryland Historical Society: Jacob Glushakow’s sensitive paintings and drawings of blue-collar Baltimore in the twentieth century and Paul Henderson’s stunning photographs of the local African American community in the civil rights era. Both soothed my jangled spirit and sparked hope: they reminded me of the gritty beauty of this city that I love, the never-ending struggle for justice, and the long and uncertain arc of history.

~ Linda Shopes lived in Baltimore full-time from 1967 to 1990 and part-time during the past two years. She teaches oral history in Goucher College’s MA in Cultural Sustainability program and is co-editor of The Baltimore Book: New Views of Local History (1991).