Rethinking the refrigerator: The surprisingly sustainable past

18 July 2013 – Briann Greenfield

I teach a course in material culture studies, so I am in the habit of using historic artifacts to think about our changing relationship with the environment. But nothing made this lesson clearer to me than a 1950s Hotpoint refrigerator.

I teach a course in material culture studies, so I am in the habit of using historic artifacts to think about our changing relationship with the environment. But nothing made this lesson clearer to me than a 1950s Hotpoint refrigerator.

When I acquired the refrigerator it was over 50 years old and looked it–there were dents, scratches, and rust decorating its exterior. Inside was a layer of grime, somehow impossible to remove. I had bought it in an act of desperation, having just purchased a foreclosed house without any appliances. The refrigerator was only $85 and came with a stove of the same vintage. I lived with those appliances for many years while my husband and I waited to rebuild the kitchen.

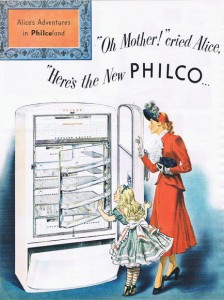

Over time, I came to love the old stove. It had built-in storage areas and well-designed gas burners. But my relationship with the refrigerator was much more strained. It worked perfectly well. In the main compartment, food stayed cold; in the freezer, it froze. But I worried that I was creating an environmental disaster. Refrigerators are high electricity users. They stay on 24 hours a day and they draw a lot of power. In the 1930s, when electric refrigerators were introduced to the home market, electricity companies promoted their purchase over competing gas models because electricity promised larger profits for the industry. Likewise, General Electric, one of the first companies to engineer home refrigerators, took on the expensive work of research and product development because of the potential to make profits in both product and utility sales.

In the last thirty years, refrigerators have become more efficient, encouraged by regulatory programs such as the U.S. Department of Energy’s conservation standards and voluntary labeling programs like Energy Star which help consumers choose more efficient models. My refrigerator clearly did not benefit from these innovations, and the fact that it was old meant that the gasket around the door was brittle and cracked, allowing cold air to escape.

But when I hooked my refrigerator up to an electricity meter, I discovered something surprising. It was drawing only about as much electricity as a modern-day refrigerator. I’m a historian, not an engineer, but I suspect two explanations, both of which illustrate how our culture supports high energy consumption.

First, the interior of my 1950s refrigerator was smaller than that of a modern unit. Household size has been on the decline for much of the last fifty years, but consumption encouraged by the convenience food industry has been on the rise. Indeed, many of my friends commented on the size of the refrigerator, saying that they would need more space for soda and other drinks.

The second explanation for the low energy draw was that my fridge didn’t have an automatic defroster, a convenience feature that became popular in the 1960s and 1970s. Having lived without an automatic defroster, I can tell you that defrosting the freezer isn’t such a big deal. In my climate, it can be done just once a year and it is a good opportunity to discover forgotten items. But defrosting becomes significant when a home life of comfort and ease becomes the marker of a middle class lifestyle. Like hanging the clothes out to dry or washing dishes by hand, defrosting the freezer is the kind of manual labor whose absence symbolizes prosperity and progress.

The second explanation for the low energy draw was that my fridge didn’t have an automatic defroster, a convenience feature that became popular in the 1960s and 1970s. Having lived without an automatic defroster, I can tell you that defrosting the freezer isn’t such a big deal. In my climate, it can be done just once a year and it is a good opportunity to discover forgotten items. But defrosting becomes significant when a home life of comfort and ease becomes the marker of a middle class lifestyle. Like hanging the clothes out to dry or washing dishes by hand, defrosting the freezer is the kind of manual labor whose absence symbolizes prosperity and progress.

I did get rid of the 1950s refrigerator when we rebuilt the kitchen and I was able to bring my energy draw significantly lower by purchasing a small unit without automatic defrost. But I still think about my old refrigerator. By allowing us to compare past practices with those of our own, history (and in this case an old appliance) helps us recognize the ways in which our domestic “needs” are culturally constructed. Rising expectations, so elegantly exposed by the historian of household technology Ruth Cowan in her book More Work for Mother, have often led to rising energy use. For us to reduce energy use, change must be more than technological. It must be cultural too.

~ Briann Greenfield, Central Connecticut State University

To learn more about the history of housework, electricity in the home, and the introduction of the electric refrigerator see:

- Blaszczyk, Regina Lee. American Consumer Society, 1865-2005: From Hearth to HDTV. Wheeling, Ill: Harlan Davidson, Inc, 2009.

- Cowan, Ruth. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

- Nye, David E. Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1990.

Neat post. There’s been an odd confluence of refrigerator discussion in my life lately. First, I ran across this blog post about the Ohio Historical Society’s new exhibit of a 1950s prefab house. The author noted “he museum could not successfully find anyone to donate a vintage 1950s refrigerator for the house. ‘Anybody that still has a 50s fridge is still using their fridge,’ he said. Yup, they don’t make ‘em like they used to.” (Post here: http://bit.ly/14VElf7). Second, I’m in the midst of Susan Strasser’s Never Done: A History of American Housework. As she discusses the adoption of manufactured appliances, refrigerators become an interesting exception. Americans who could afford to rushed to purchase stoves and furnaces first – the messiest and hardest-to-fuel appliances before electricity. And they embraced lots of other electrically powered gadgets, including the home washer. But people were slow to adopt electric refrigerators – partly because it was not clear that they represented much of an advantage over iceboxes, which worked pretty well. She mentioned energy cost as a concern and notes that the automatic defroster is a big energy hog; she also talks about how bigger fridges drive more cold storage of food at home and thus more consumption of “fresh” food (as opposed to frozen, canned, dried etc), driving up the demand for out-of-season produce. All very interesting!

Thanks Michelle. That Lustron House project at Ohio Historical is too cool. I love that people are invited to touch everything.

I liked this post a lot. When I first came across it I thought it was going to be about how Americans have to have bigger refrigerators because we have all become addicted to fast frozen food. I was pleasantly surprised that it was focused on how we were wrong in assuming old appliances are energy suckers. Personally I like the look of the old fridges and would be thrilled if my house came with one! Great post!

It really is surprising, how less electricity they consume. May be you are right with those 2 reasons why it consumes less energy.

The smaller size might be the reasons it consumes less energy.

Is there any way you can get me a model number off the refrigerator? I am trying to get some technical data for my exact fridge as yours but cannot find the model number. Wish mine looked as good as yours but it does still work?

A 1950s-sized fridge is fine for a family if mom stays home and shops every couple of days for food.

YOU clearly don’t need a larger fridge. But actual families do, unless mother is, indeed, to have MUCH more work. You snipe about “convenience foods.” Nonsense. It’s the produce that absolutely destroys refrigerator space. People eating convenience foods mostly dine out of a freezer–and chest freezers sip electricity.

This makes me think of Dolores Hayden’s book “Building the Suburbs.” Good stuff (both the book and your post).

I think if modern refrigerators are energy hogs its because they do so much. They dispense cold water and ice and automatically defrost yes and that adds up energy consumption. Plus the walls are not nearly as thick/thickly insulated as the old 50’s jobs. And the newest models have their condensing coils on the bottom where they really really attract and get covered with thick greasy kitchen dust that makes the machine run harder. It’s amazing to me how many dumb young homeowners don’t even realize this. I like to give newly weds a nice long bottle brush which works really well to reach in under the fridge and clean those dusty coil grids. Older models had the coils up and down the back side where they did not attract so much dust.