Rust, recreation, and reflection

27 October 2017 – James F. Brooks

Editor’s note: We publish TPH editor James F. Brooks’s introduction to the November 2017 issue of The Public Historian. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members.

I recently spent several weeks exploring the remnants of coal towns in southern Colorado, as well as associated public history interpretive sites like the United Mine Workers’ (UMW) memorial at the site of the Ludlow Massacre, the Walsenberg Coal Mining Museum, the Cokedale Mining Museum, and the Steelworks Center of the West in Pueblo. The region is most remembered, at least among labor historians, as the location of the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, in which thirteen women and children died. The UMW memorial receives public visitors with a time line of illustrative panels that detail the labor dispute, the strikers’ colonies, and the siege laid by the Colorado National Guard. The museums tend to emphasize the diverse ethnic and racial composition of the coal camps, workers’ life underground and family life above, and aspects of “welfare capitalism” in the Colorado Industrial Plan that emerged after public outcry following the violence at Ludlow.

I recently spent several weeks exploring the remnants of coal towns in southern Colorado, as well as associated public history interpretive sites like the United Mine Workers’ (UMW) memorial at the site of the Ludlow Massacre, the Walsenberg Coal Mining Museum, the Cokedale Mining Museum, and the Steelworks Center of the West in Pueblo. The region is most remembered, at least among labor historians, as the location of the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, in which thirteen women and children died. The UMW memorial receives public visitors with a time line of illustrative panels that detail the labor dispute, the strikers’ colonies, and the siege laid by the Colorado National Guard. The museums tend to emphasize the diverse ethnic and racial composition of the coal camps, workers’ life underground and family life above, and aspects of “welfare capitalism” in the Colorado Industrial Plan that emerged after public outcry following the violence at Ludlow.

Gaston Gordillo’s 2014 book, Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction, also haunted my mind throughout. This anthropological exploration of conquest and industrialization in the Argentine Chaco treats the various meanings that peoples of different classes or races attribute to the visible remnants of these phenomena. A simple rendering of his thesis suggests that we keep in mind a distinction between “rubble”—the detritus that remains after conquest and industrialization of a hinterland—and “ruins”—the affect constructed through historical interpretation of the same remnants (often informed by bourgeois nostalgia)—that smear a pain-masking salve over the past.

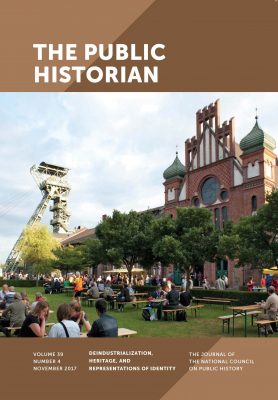

This special issue of The Public Historian also occupied my thoughts, since the essays herein illustrate the tensions between “preserving” the hard lessons of our industrial pasts for public enlightenment and redeveloping postindustrial sites for tourism and public recreation. As our guest editors, Christian Wicke, Stefan Berger, and Jana Golombek, make clear, what appeals to many urban-dwelling, tech-savvy, digital-economy visitors as the gritty romance of an era gone by bears little resemblance to the grindingly dangerous toil that unfolded beneath the ground and within the factories in the Ruhr, Australian and Romanian coal camps, post–Motor City Detroit, and Glasgow. In this global view, the guest editors’ contribution reminds us, “industrial heritage . . . is sometimes presented in a self-congratulatory way,” severed from critiques of the experience of the working classes who made it possible.

As gentrification turns the “blighted structures” and industrial flotsam into commercial collectibles of “industrial heritage,” these authors worry that such transformations are perceived as a “universal good,” which in more critical analysis trends toward erasing “the social and material legacies of racism and urban decline from the landscape.” Yet in the southern Colorado coalfields, public history sites and projects suffer thin visitation, since none feature the magnetic appeal of food courts, playgrounds, and recreational options that attract non–historically minded travelers to experience the educational and interpretive work of dedicated local historians.

This special issue illustrates the varieties of critical stances and renditions practiced by public historians on three continents. All suggest that the industrial past continues to resonate, in various ways, in our new-economy present. As we have recently seen, the nostalgia for an industrial past continues to shape self- and national identity and can sway electoral politics. We hope to contribute to a greater understanding of how economic change, memory, heritage, and political symbolism intersect.

~ James F. Brooks is editor of The Public Historian and professor of history and anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.