We need public histories of organized labor

25 January 2013 – Richard Anderson

Thousands march on Lansing, Mich., to protest anti-union legislation called “Right to work.” Photo by PW/John Rummel

Two thousand and twelve was another wrenching year for American workers and labor unions. The time seems right for public historians to recover organized labor’s past and to place that history at the center of our current public policy debates. What kind of year was it for workers? The economic “recovery” has been tepid, and corporate profits are recovering much faster than wages. Unemployment hovers just under 8%. Workers who kept their jobs are logging more hours and performing more tasks for the same pay. How did unions fare in 2012? The mostly successful strike at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and the highly publicized Thanksgiving actions against Wal-Mart were encouraging. Still, following legislative attacks on public-sector unions in Wisconsin and Ohio, and a similar campaign of vilification by my governor in New Jersey, anti-union “right-to-work” laws were enacted in Indiana and Michigan. There was heavy symbolism in Michigan–so long portrayed as the cradle of organized labor and the epicenter of the once-mighty United Auto Workers–embracing the union-busting mechanisms provided for by the 1947 Taft-Harley Act.

As the reference to Taft-Hartley suggests, current anti-union animus is nothing new. Historians continue to debate how much power unions truly possessed during labor’s “golden age” in the 1950s. Still, today’s unions operate in very different circumstances than their predecessors. During the heyday of postwar collective bargaining, many unions negotiated generous contracts with cost-of-living adjustments, overtime provisions, and paid vacations. This system of labor relations was part of larger New Deal political order that served as the governing orthodoxy of the United States between roughly the 1930s and late 1970s. The New Deal order was propelled by a private manufacturing economy stimulated by tremendous levels of public spending.

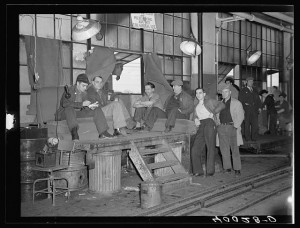

Strikers guarding window entrance to Fisher body plant number three. Flint, Michigan, 1937.

Photo courtesy of Libary of Congress

High wages and stable employment provided workers with the purchasing power necessary to consume at a high level. The federal government provided unions with some degree of legal protection, to which corporations acquiesced within limits, in exchange for stable production. Millions of Americans–particularly women and minorities–were excluded from this system. Historian Jack Metzger acknowledges the pitfalls of idealizing this era in Striking Steel, his memoir about growing up in a steelworker’s household. Yet Metzger gets to the heart of the matter by noting that “[w]hat was better then was the direction we were going.”

The New Deal order died ignominiously during in the 1970s for reasons too complex to discuss here. Today the structures of our economy and the values embedded in our system of labor relations are fundamentally different. We now have a postindustrial service/knowledge economy in which high finance is king and workers enjoy few benefits and little job security. Overall union membership rates have plummeted from a high of 35% in the mid-1950s to 12% in 2010. Yet politicians talk as if a few tweaks to the system could return us the age of postwar prosperity. President Obama told last summer’s Democratic convention that “[o]urs is a fight to restore the values that built the largest middle class and the strongest economy the world has ever known, the values my grandfather defended as a soldier in Patton’s army, the values that drove my grandmother to work on a bomber assembly line while he was gone.” But the president’s soaring rhetoric belies the fact that the economic structures that undergirded the Greatest Generation no longer exist. Conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer was more clear-eyed when he noted in reference to Michigan’s right-to-work law that the postwar era of union strength was “not a norm but a historical anomaly.” He’s right. The New Deal order was, in the words Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore–two historians sympathetic to the labor movement–a “long exception” in American political culture. Unlike Krauthammer, however, I lament the waning of labor union strength and do not think it was inevitable. Politicians, policymakers, business leaders, even union leaders themselves made decisions that decimated American manufacturing and fatally constrained the ability of organized labor to mount an effective response.

Public historians should address this state of affairs. The struggles of workers in 2012 present public historians with an opportunity to narrate the trajectory of organized labor during the second-half of the twentieth century, linking labor’s past to the present material concerns of ordinary Americans. We should start from the premise that the contemporary degradation of workers and labor unions is part of a broader history of political economy in the United States.

I know, I know. Political economy–which examines the impact of economics on a society’s politics, social structure, and ideology–sounds hopelessly abstract and academic-ish. But it highlights issues like deindustrialization and the growth of the retail sector that are central to understanding current policy debates. The weakening of New Deal-era legal protections for workers is anything but abstract and academic to the employees attempting to organize Wal-Mart, the embodiment of postindustrial service employment.

How can we produce public histories of the labor movement that address important questions of political economy? Op-eds, blog posts, and academic texts are good formats for explaining capital flight, industrial policy, and tariffs, but they don’t allow for the kind of interactive experience that would connect today’s economically squeezed workers to the history of the New Deal order. I don’t want to suggest that no labor historians and public historians are thinking along these lines. The September 2009 edition of the journal International Labor and Working-Class History was devoted to public history. One of the essays is co-authored by UMass-Boston professor of history James Green, whose work exemplifies the possibilities of wedding labor- and public history. Last June the Alberta Labour History Institute held what looks to have been an exciting conference on public history and Canadian labor. And speaking of Canada, the upcoming NCPH conference in Ottawa will feature a walking tour of the city’s labor history.

I have more thoughts about walking tours, traveling exhibits, and heritage tourism, but I’ll save them for my next post. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts or learn about examples of public history that addresses the labor movement and/or the New Deal order.

~ Richard Anderson is a doctoral student in twentieth-century American history at Princeton University

Great article, Rich. When you say “We now have a postindustrial service/knowledge economy” you’re talking about the U.S., right? As you know, this certainly isn’t the case in China, Bangladesh, and much of the global South. It seems to me that another way public historians can be useful to labor struggles is by offering internationalist histories and analyses. I also applaud your use of “political economy.” Public history doesn’t need to be anti-intellectual, and there was a time when it was not unusual for wage-workers to get together to study and discuss Das Kapital.

Thanks for your thoughts, Dan. You raise a great point about the geographic specificity of “postindustrialism.” Even in a strictly domestic context the term is problematic because many American regional economies/industries feature very “old” problems of exploitation and coercion. (Two friends who are labor lawyers in Georgia spend a lot of their time addressing such issues.) As to internationalism, this is huge. Jefferson Cowie’s book Capital Moves makes a strong case for treating labor history in a transnational context, as does Dana Frank’s 2004 article, “Where is the History of U.S. Labor and International Solidarity? Part I: A Moveable Feast,” in the journal Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas.

I really enjoyed this article.

I also posted this as a comment on the NCPH Facebook page, but I wanted to share the information here as well:

“The Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects websites, directed by James N. Gregory at the University of Washington, might serve as a model for other such public history websites. The eleven projects bring together nearly one hundred video oral history interviews and several thousand photographs, documents, and digitized newspaper articles. Included are films, slide shows, and lesson plans for teachers. The projects also feature dozens of historical essays about important issues, events, and people, many written by undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Washington. Indeed, the success of the project spawned the creation of a new labor archives at UW to help support this and other such projects. http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/ “

Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts and providing a link to your website, Conor.

I grew up in Flint Michigan and now live in Butte, Montana – I guess I am attracted to blue-collar labor-oriented towns. In Butte, the rich labor history is incorporated into the trolley tours I do (we have five drivers, I interact with about 700 tourists a year on the trolley) and on walking tours through Old Butte Historical Adventures (around 3000 a year; my share is about 750) and others. I have a special labor history walking tour that we do on demand, but all those other visitors get at least the overview. There are several books that focus on Butte’s labor union history, the most important of which is probably The Gibraltar, by Jerry Calvert (as in The Gibraltar of Unionism, one of Butte’s many nicknames).

Thanks for sharing, Richard. Butte does indeed seem to be a place rich with possibilities for merging labor- and public history, as your own work indicates. I drove through the city a few years ago (unable to stay as long as I would have liked) and was sufficiently taken with it to briefly consider focusing my dissertation on it. But as you note, several historians have already turned their eye on the city.

I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on heritage tourism and how you might see some of this history being conveyed to a general public visitorship that isn’t necessarily seeking it out (for instance by signing up for a labor history walking tour). The resurgence (thanks Downton!) of interest in the “downstairs” servant staff has provided us with an opportunity to bring forward the personal stories of many of the workers (not just those serving in the house, but the farmers, laborers, builders, artisans and many others) at a couple of our historic home sites but the interest is more of the voyeur variety and I would love to find some ways to use the programs and tours to bring people’s attention to present day labor issues.

Thanks for your comment, Kate. When executed with care, heritage tourism can certainly do some of the work I’m advocating in this blog. (For brevity’s sake I’ll sidestep the vexing question of whether heritage tourism commodifies the past.) And I appreciate the way you frame the question as one of bringing labor history to visitors who aren’t necessarily seeking it out. Monticello’s slave quarter tours do a wonderful job of integrating the story of the slaves’ everyday lives and their work into a broader narrative about Jefferson’s home, but I suppose the folks who sign up for those tours know that they’ll be getting such a story. I think that a thoughtful tour script and tour guide/exhibit text also helps move the experience away from one of voyeurism.

Some work on working class history or labor history and memory can focus attention on the monuments to workers: statues, plaques, and sites around the US and in Canada. My favorite is the Australian monument to the 8 hour day in Melbourne.

I’m very interested in moving labor/public history ahead and have done (scripted & co-narrated) an 18-minute film for SEIU (with help from Gail Friedman & Lisa Paul) re labor and SEIU history. I’m also very near completion of a ms. “Liberty and Labor: The United Electrical Workers and the Enemies of Industrial Democracy in Erie, Pennsylvania, 1930s-1970s,” pieces of which I’ve presented to both academic and labor audiences over the years (for one, see “The Cold War Comes to Erie, 1946-1956: Repression and Resistance” in FEAR ITSELF, ed Nancy Schultz [Purdue: 1999]). Let’s talk about possibilities. (717-649-8085).