Preservation conversations: When history at work is history at home (Part II)

21 September 2012 – David Rotenstein

Before the mid-1960s, except for domestics and a few other exceptions, South Decatur was exclusively white. It was a place Decatur’s blacks knew to not be after sundown. They knew that they were welcome to clean houses, cut lawns, and bag groceries there during the day but the suburban dream being lived by their white employers was beyond reach. Things began to change as white flight transformed neighboring Atlanta neighborhoods and a turning point was reached in the 1960s when the City of Decatur embarked on a second phase of urban renewal in the historically black neighborhood known by its residents as the Beacon Community and by whites as “Nigger Town.”

Displacement created opportunity and the Beacon Community’s former renters, boarders, and homeowners began buying homes in South Decatur. Suddenly, the dream of becoming a suburban homeowner was becoming a reality. As the number of black homeowners increased, whites fled. The number of whites decamping from South Decatur spurred the Decatur City Commission in 1966 to enact an ordinance banning real estate signs on residential properties. Discriminatory lending practices (some of which persisted into the late 1980s resulting in the landmark U.S. v. Decatur Federal Savings and Loan case) combined with new homeowners unprepared for the challenges of homeownership and an aging population of whites who remained behind created conditions in the early 1970s that made the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development the leading residential property owner and manager in the city.

Watching houses carted off to landfills weekly and listening to heart-wrenching narratives from elderly African American homeowners who were describing the almost daily entreaties from builders and their agents to buy their homes so that they could be torn down to accommodate new McMansions became troubling. Anyone familiar with the literature on urban renewal knows the violence done to communities and people by the process. Urban renewal, like the demolition and building boom underway in our new neighborhood, began with polite letters and visits to economically disadvantaged households. I interviewed Decatur’s first African American mayor, a former public housing resident and one of the first African Americans to move into South Decatur. The 80-year-old woman compared conditions in her 2012 neighborhood to her 1960s neighborhood. “This is not government funding, what’s happening in here,” she told me. “This is a developer, private, who can afford to buy up these properties and then build.” (See the video in Part I for excerpts from that interview.)

Watching houses carted off to landfills weekly and listening to heart-wrenching narratives from elderly African American homeowners who were describing the almost daily entreaties from builders and their agents to buy their homes so that they could be torn down to accommodate new McMansions became troubling. Anyone familiar with the literature on urban renewal knows the violence done to communities and people by the process. Urban renewal, like the demolition and building boom underway in our new neighborhood, began with polite letters and visits to economically disadvantaged households. I interviewed Decatur’s first African American mayor, a former public housing resident and one of the first African Americans to move into South Decatur. The 80-year-old woman compared conditions in her 2012 neighborhood to her 1960s neighborhood. “This is not government funding, what’s happening in here,” she told me. “This is a developer, private, who can afford to buy up these properties and then build.” (See the video in Part I for excerpts from that interview.)

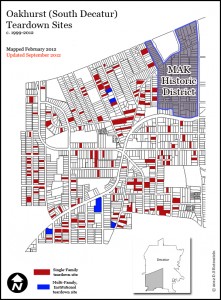

As I was documenting the teardowns, new construction, and changes in housing from 1890 through the first decade of the twenty-first century, I made the mistake of mentioning the neighborhood’s name in combination with the words “historic preservation” on local blogs. I made the bigger mistake of using words like “gentrification,” “McMansion,” and “white privilege” in an online environment dominated by the people building and buying the new homes that were, in my opinion, destroying the physical and social fabric of the neighborhood. I had hoped that there were people–neighbors as well as elected and appointed officials–who would listen to my suggestion to take a step back from the pace of development to re-evaluate an incomplete citywide historic resources survey, sustainability goals, stormwater management, and most importantly, the preservation of small, affordable homes.

White privilege is an unrecognized and widespread phenomenon in Decatur. Residents map their values and perspectives onto the African American community when evaluating the community costs and benefits of teardowns and new construction. The filter also covers history. African Americans are so completely marginalized in Decatur that a 2009 citywide comprehensive historic resources survey omitted all mentions of the once-thriving African American community there. The absence of African Americans from the city’s official preservation planning document is underscored by the number of designated and protected African American heritage sites: None. That doesn’t mean they don’t exist; it only means that the City and, by extension, its residents, don’t see fit to acknowledge them. Despite assertions by the City that its 2009 survey was reviewed by the “public,” no one seems to have caught the fact that the words “African American” and “black” appear nowhere in the 75-page document.

Conversations and email exchanges with city commissioners and the assistant city manager were unsatisfying, to say the least. After more than a decade in Washington, my wife and I were highly attuned to being handled and dismissed. So we had to confront our options. Should we stay in the neighborhood knowing that our values were in the minority or should we cut our losses and move out of Decatur? We sold our home after just 11 months–it’s a hot real estate market and we had an offer within minutes of its first off-market showing–and we moved next door to Atlanta. Our new neighborhood underwent gentrification, too. The difference, though, is the gentrification left much of the historic environment intact (excluding, of course, the large corridor cleared for an aborted highway in the 1960s). We can come home each day and know that the neighborhood we call home will look the same as it did when we left in the morning, including the historic houses, small and large.

I will be working through the ethical and moral challenges I faced while living in Decatur as I write an oral history of housing in South Decatur that turns on the dollar home program. More than 30 houses within a half-mile from our Decatur house were torn down or slated for teardown between the first week of September 2011 and the first week of August 2012. The research raised my awareness of the environmental and social justice issues in the new neighborhood, but it presented me with a dilemma: Sit back, observe, and leave with a boatload of data? Or, should we become stakeholders where we invested and try to change things? One writer on a local blog dispelled that idea in a March 2012 comment: “I kinda find it ironic, as someone who has lived in Decatur since, yikes, 1989, that he, who moved here a year or two ago, comes along and complains about how Decatur is SUPPOSED to be!”

Contrary to the blog contributor’s comments, I wasn’t exactly a newcomer to her community. I had lived in the Decatur area (with a Decatur zip code) in the 1980s as a Georgia State University undergraduate. My published and unpublished work on Georgia (and Atlanta area) history includes more than a hundred cultural resource management reports written between 1984 and 2004 and two published articles on early twentieth century Atlanta area blacksmith shops. My writing on Atlanta’s blues scene in the early 1990s continues to be cited by music writers and ethnomusicologists. Despite the blog commenter’s assumptions about tenure in the community, I’m not sure it is relevant to someone’s status as a stakeholder in a place’s past, present, and future. I think anyone–regardless of academic credentials and experience–has a right to an opinion, informed or otherwise.

~ David S. Rotenstein (Historian for Hire) is an independent consultant working in Atlanta, Washington DC, and beyond. The oral history clips in the video below were recorded during 2011 and 2012; the video was played during a May 2012 DeKalb History Center lecture on South Decatur’s housing history.

Fascinating! Thank you, David.

Thank you David. South Decatur was home for 35 years to Bill and I and our three children. Many good memories of so many good friends and neighbors working together for a better South Decatur. They were special times. Please keep in touch and the best to you and yours.

After much reflection I have come to some resolution with what my wife and I call the “Decatur experience.” The interviews and research I did was unsolicited and unfunded. I did it because as a historian who deals with material culture — researching people, places, and things — is in my DNA. In all likelihood the interviews, originally destined for the DeKalb History Center, will never see the light of day nor will much of the research. I will do what many of Decatur’s current residents and stewards of their history and culture have asked me to do: I will leave it behind and move on.

On a Delta flight returning to Atlanta from Washington I composed this letter to the people of Decatur and I posted it on my blog:

Dear Decatur,

I apologize.

For me, Oakhurst’s teardowns stopped being a “historic preservation” issue soon after I got to know the people most affected by them: Decatur’s elderly African American homeowners who live in the neighborhood. Back when Oakhurst was known as South Decatur, it was a community that went from a desirable suburb to a blighted inner-city neighborhood in the space of a single generation. South Decatur before 1970 was a mostly white area. After 1970, it became majority African American and it remained a mostly black neighborhood until successive waves of gentrification and municipal rebranding began turning back the demographic clock.

By the first decade of the twenty-first century, many of the African Americans who had bought South Decatur homes were elderly bystanders as younger and more affluent people began moving in and reshaping the community’s landscape and culture. Many of those older folks, community anchors as one local pastor calls them, had become homeowners at a time of great pain and tremendous opportunity in Decatur’s black community. The 1960s were a difficult time for Decatur’s African Americans because the city had embarked on a second wave of urban renewal in the historically black part of town known as the Beacon Community. People, homes, businesses, and churches were being involuntarily displaced to “cure” urban blight. At the same time Decatur’s blacks were being displaced, the nation was undergoing a civil rights reawakening and moral re-centering. Racial barriers were being dismantled in education, voting, employment, and home ownership. African Americans moved into South Decatur against that backdrop of local, regional, and national culture change.

After interviewing dozens of people affected by urban renewal in Washington, D.C., and the people who spent decades trying to revive broken neighborhoods and broken lives, I was keenly aware of urban renewal’s costs and its lingering impacts decades after the last homes and churches were demolished and new public housing and private-sector residential developments were completed. Ethnographers, historians, and urban planners have been writing about these effects for decades. The narratives I had begun collecting in Decatur closely resembled what I had helped to document in the nation’s capital and in the literature that is essential reading for anyone working in urban history.

The difference, however, with Decatur was that current real estate market conditions were making Oakhurst’s elderly residents targets for builders who want to buy their small, oftentimes debt-free, homes to tear them down so that newer, larger homes may be built. In most any other community, changes in buildings and in people is nothing extraordinary. The market forces propelling home sales and new construction wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. But because of South Decatur’s peculiar history, those market forces are re-victimizing people who had gone through one or more urban renewal episodes. Add to those stressors Decatur’s crushing property taxes and Decatur can be a very unpleasant place to live for some folks.

And what of the people who, according to some Decatur writers, have “tapped their greatest asset” by selling their debt-free homes and exchanging a familiar lifestyle for a new community with new housing costs and new lifestyle challenges? Their stories are not as positive as the people who presume to speak for them in blogs and email lists suggest.

Decatur’s younger and more affluent newcomers don’t recognize the constant calls, letters, and visits from builders as harassment because it’s all just part of the market at work. The people who are on the receiving end of the uninvited contacts describe it as harassment and they compare it, and the constant demolition of homes around them, to the painful urban renewal they recall. Whether they experienced it as children, young adults, or in their family’s stories, the pressure to move from a familiar place and away from friends and families is as much a part of their heritage as Ellis Island and growing up in an anti-Semitic Southern community are part of mine.

When my wife and I became Decatur homeowners, we became invested in the community. Because my professional life involves the past as well as its artifacts — buildings, landscapes, and sites — I tried to articulate my concerns for those things and for the people who live among them. I used what my wife called my “FIRE!” voice because of how rapidly Oakhurst’s landscape was changing just in the brief period of time we lived there. I interfered and said things people don’t want to hear about themselves, their neighbors and friends, and their community leaders. I was wrong to assume that my voice would have any greater impact on the community than all of the people — historic preservation advocates, affordable housing proponents, and environmentalists — who had been working from the inside to improve things for years before we moved to Decatur. For that hubris I am truly sorry.

Sincerely,

David S. Rotenstein, Ph.D.

December 7, 2012

@30,000 feet somewhere between Washington, D.C., and Atlanta, Ga.