An interview with E.G. Crichton and Julia Brock

(Read the introduction here and the series overview here. This page was posted April 12, 2013.)

Poster for LINEAGE: Matchmaking in the Archive, a project series and exhibition by E.G. Crichton for the GLBT Historical Society, 2009. Courtesy of E.G. Crichton.

Brock: How would you define or describe your work at the GLBT Historical Society?

Crichton: I play different but overlapping roles: artist-in-residence for the GLBT Historical Society, member of the Board of Directors, and member of the curatorial committee for the GLBT History Museum.

How did your partnership with the GLBT Historical Society begin?

In 2008, a board member queried me on whether I’d consider joining the board. On impulse, I said that what I really wanted to do was become an artist-in-residence. This idea was appealing to me as a way to work as an artist, especially given my interest in queer history and past work with the organization.

What are the parameters of that partnership? For example, was the scope of your role set out in a formal agreement?

When I first proposed this idea, the response was “What is an artist-in-residence”? After convincing them I did not expect to camp out in the archives (!), we agreed to come up with a formal agreement that described the parameters of my position. I developed a proposal that included several ideas for how I could start working with the archives and the organization. Together, we hashed out terms such as “no salary,” a three-year “contract,” and compliance with the rules of the archives, etc. It was a very friendly process, led by one particular board member, Don Romesburg, who was especially interested in fostering this as a new way of thinking about the relationship of art to the archives.

Are there any limitations imposed on your work there by stakeholders such as staff, board members, or the public?

It is important that I keep everyone informed, and of course that I act with respect for organizational authority such as that of archivist and executive director, but in general I have been given considerable freedom to use the archives and enact my ideas. The way I have framed my role and brought projects to fruition has engendered a lot of trust; it has also brought new people and resources into the sphere of the organization.

Image from LINEAGE: Matchmaking in the Archive, 2009, GLBT Historical Society. Courtesy of E.G. Crichton.

Is your partnership a replicable one for other history institutions and artists?

Yes. Actually, a number of history and other institutions have created artist-in-residence positions. This is especially true in Europe and Australia. The London School of Economics, for example, has a long-standing program in which artists conduct research and create a body of work or installation related to the history of the institution. One of the most original artist-in-residence programs in the U.S. was started by artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who in 1977 convinced the New York City Department of Sanitation to appoint her artist-in-residence. To this day, she continues to collaborate with them in making work that relates to issues of sanitation, land fill and other environmental concerns.

Has your work changed, or even transformed, the GLBT Historical Society?

In some ways, yes. I think the assumption at first was that I would create a series of solo artworks that respond to the archives in some way and then are exhibited in a gallery. But I see my role more as that of an artist-catalyst, creating social frameworks for participation with the archives. I’m interested in helping shepherd the incredible histories embedded in the archives off their shelves and out into imaginative accessibility. Part of my motivation for creating this artist-in-residence position was to introduce new more interdisciplinary forms of art, to shake up a field of queer art that I have grown tired of. I think that has happened, and I’ve seen people be moved by the results. After the first exhibition of LINEAGE: Matchmaking in the Archive in summer, 2009, the board invited me to become a board member. This coincided with efforts to open a dedicated GLBT history museum, and I think people realized I could contribute to this. It was also a kind of validation of the work I’d been doing all year, and I think my projects have suggested new ways art can strengthen an organization like the GLBT Historical Society.

Has your work generated new audiences there?

I have consciously framed my projects to include people who were unfamiliar with the archives, and especially people who are under-represented in the collections—women, people of color, trans men and women. The archives relating to their interests and identities take up far less shelf space than white gay men, so my longer-term goal has also been to draw more diverse archive donations. I have brought a number of my students into the projects, people in their early to mid-twenties who become passionately engaged. At public events related to the LINEAGE projects, the audience has been standing room only with many new faces.

Is your work intended to be, implicitly or explicitly, critical of traditional archival and historical practice (wherein archival access is largely a privilege of professionals and historical knowledge is imparted via textual sources and cohesive, large narratives)?

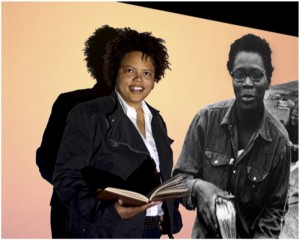

Tina Takemoto with possessions of Jiro Onuma, her match in the archives. Part of the LINEAGE: Matchmaking in the Archives project. Courtesy of E.G. Crichton.

Criticism has never been my starting point since I have a lot of respect for the archive and historical processes you mention. But I did come into this work with an awareness how art can sometimes intervene in different, more accessible ways. One goal I stated from the outset was “to bring the archives off the shelf into creative visibility.” There’s a kind of slippage that art processes make available because of not being bound by other disciplinary structures. This is most evident in the ways artists can fill in gaps in the record to address not only what is present in an archive, but what is absent or invisible. I’m sure historians have to do this too, but as an artist, I can play with documentary “truth” in more flexible ways.

Would you consider your work to be restitutive of queer history in public memory? Do you consider the truths that emerge from your work to be historical truths?

I’m definitely motivated by a desire to bring ignored and invisible queer history into public awareness. My initial instinct was really quite personal and individual: a desire to figure out why I am a lesbian and who I can look back to as antecedents. I come from a family that kept a lot of secrets, so on some level my detective efforts started at a young age. I wanted to KNOW about what was unspoken. As for “historical truths,” I’m not sure what that means—to me or to the discipline. There have been times when I’ve been nervous about playing fast and loose with the truth—such as when I was making rubbings of gravestone epitaphs [in the Rise, Sally, Rise project], knowing I would manipulate them in some way. I kept looking over my shoulder to make sure a relative wasn’t watching me! More recently, the thought of a relative or lover seeing the work that emerged from my matchmaking process made me nervous. I am aware that the distance of responding to artifacts in an archive can be in tension with the feelings of someone who mourned an actual person.

Portrait of Dominika Bednarska with her match, Diane Hugaert. Crichton took portraits of the first nineteen participants with their match from the archive. The images have been exhibited as framed pictures in the first LINEAGE show, as animations (showing multiple views of each matched pair as stop motion sequence) for the second LINEAGE exhibition, and in digital form on Crichton’s website and also the website for the Queer Cultural Center in San Francisco.

In the LINEAGE project, you are not only artist and historian, but matchmaker. Will you explain the genesis of the work?

At some point in my research in the GLBTHS collections, I became aware of historical crushes I had on a couple of (deceased) women, just based on the content of their archives. One of my friends coined the term “historical promiscuity,” which seemed the perfect designation for how desire intervened in my research process. I truly felt like I was cruising the aisles, looking for archives that turned me on. And if this could happen to me, why not to others who I would bring in to the archives? I started to look at particular collections of individuals who were dead and think “Who would be drawn to this person? Who would be inspired by this archive to respond imaginatively?”

What is your process of matching the living and the dead?

It first I relied largely on demographics and similar interests: I matched performance artist Lauren Crux to singer/songwriter Jannie MacHarg, disabled lesbian Dominika Bednarska to disabled lesbian Diane Hugaert, for example. But in time, I went more by instinct (as I honed my matchmaking skills!) and also thought it would be more interesting to shake up the expected demographics a bit: Bill Domonkos to WWII flight instructor Helen Harder, African American accountant Troy Boyd to Chinese American activist George Choy, etc. I made formal introductions for each “blind date” at the archives, bringing out the relevant boxes or folders, then leaving the participant alone to start to get to know the person in the archive. I always explained that someone could turn down my selection and I’d find another, but no one ever took me up on that offer. In a couple of cases where I wasn’t sure, I gave people two or three choices.

There are now fifteen new participants waiting for the next chapter in this project. Some are already matched; for others I need to return to my old cruising ground, the aisles where I locate just the right collection. People die. New collections arrive at the GLBT Historical Society, new kids on the block, waiting for their official spot on the shelf.

You have made matches within the locality of the Bay area, but in Wandering Archives you cross geographical and cultural borders to match archives with living counterparts (in Portugal, Australia, and the Philippines). Have these wanderings created different processes and results, or have new truths emerged about the archival lives that have become “guest immigrants” in other countries?

This “wandering” work is taking different forms. The first project came about unexpectedly when I presented Lineage at a conference in Brisbane, Australia. Karen Charman, a lesbian academic and cultural activist from Melbourne, was also presenting, and we became interested in the overlaps in our interests. Because she writes about autobiography, I ended up matching Karen to an unpublished memoir about lesbian lovers who got together in the 1930’s. Long distance, we wrote about our personal responses to each of the women, crafting this into a kind of visual paper/performance and taking that to a conference in Evora, Portugal (where same sex marriage had just been legalized). I really felt like I was taking a new kind of archive across national borders—both Australia and Portugal—and metaphorically bringing these two women post-mortem to a place where their relationship would be honored. That’s when I started to imagine Wandering Archives as a conscious plan.

From the opening reception of Migrating Archives, on current exhibition at the GLBT Historical Society. Courtesy of E.G. Crichton.

Next, a colleague sent me the request for proposals for a multi-venue exhibition in Manila called “Nothing to Declare.” With all of the implications of this in Philippine history, I also felt like it had resonance for LGBT issues in terms of displacement, looking for community, crossing borders. They accepted my proposal to create a kind of archive exchange across the Pacific, which led to me carrying nine creative archives in a suitcase as the basis for a museum installation. I invited eight others to create an archive based on a life that has passed. While in Manila, I connected to a wonderful restaurant and history/cultural center named Adarna owned by two lesbians who donated a creative archive for me to bring back.

The archive from Manila became one of twenty-three archives I created and carried to Amsterdam last summer for a conference on Archives, Libraries, Museums and Special Collections (ALMS) that has a queer focus. The conference had accepted my (somewhat unorthodox) proposal to create an exhibition of what I called “delegate archives” from queer archive organizations around the world. I simply wrote people and invited them to select one or two archives from their collections to represent in some way. Most organizations responded with enthusiasm, sending me digital images I could print. I prepared a more polished version of the Amsterdam show for the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco. It is called MIGRATING ARCHIVES: LGBT Delegates from Around the World, and opened February 1.

E.G. Crichton’s “Lineage: Matchmaking in the Archives” project connected living people with archival partners. Here, Elisa Parry with Pat Parker. Portrait by and courtesy of E.G. Crichton.

The Lineage project has created dialogue about the function of archives (see Gabriella Ripley-Phipps and her work, “Archival Dinner Party”) and has even inspired individuals to project how they might build their own personal archives. Do you intend for your work to foster this kind of reflexivity and critical engagement about how history is written and the political texture of that process within your audience and co-collaborators?

Yes, definitely. That has been a conscious goal from the beginning, though there is much I still haven’t gotten to. For example I would like to create more situations where people involved in my projects interact with each other. This may happen with my new notion of matching archive to archive, creating speculative relationships between archived people, which would of course involve live participants. There are three archives about individuals who were involved in World War II in deeply contrasting ways who I would love to “introduce.” I may also branch out from the archives of individuals…maybe match an archived individual to an organization, or historical event or protest. This will require that I go back to the archives with fresh eyes.

How does the LINEAGE project transform what we know, or what we can know, about the past?

I hope it opens up a sense of engagement with the past that is passionate and imaginative, and perhaps also strengthens a sense of lineage that is unique in queer communities. That has been my own need, which in turn drives my ideas.

What pasts are visible or knowable to artists, or those working in artistic mediums, that historians or archivists cannot (or do not) access?

I feel a sense of freedom as an artist from the disciplinary expectations that I imagine historians are bound to, at least within academia. It’s the other side of being so invisible in U.S. culture and having to work with such limited resources and support. I can borrow methods and knowledge from history as I do from other disciplines as a kind of amateur, a perpetual dilettante. In relation to archivists, I am much freer to create archives, fill in gaps, reproduce what’s absent. The whole notion of migratory archives that I’ve been working with goes against the archivist’s mandate to preserve, catalogue and protect the uniqueness of a particular archive. In my projects, archives become far more fluid, they morph and move and expand and transform into other forms.

Have you drawn upon the work of historians in your conceptual process?

Not in any kind of direct or disciplined way. It’s more that I search for history like a detective as I go along, on the internet, in the microfiche records of a library, through interviews and of course by sifting through archives. Throughout, I often read historical accounts, which have a less direct impact. When I started researching soap, I encountered Anne McClintock’s Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest, which had a huge impact on how I presented my work at that time.

Has there been reaction to your work from that community?

I’ve had some interactions with individual historians that have been very positive. The board member of the GLBTHS who first encouraged my becoming artist-in-residence, Don Romesburg, is a historian. Another important connection has been historian Graham Willett in Melbourne, Australia, who for years was the president of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives. Graham and I met in Melbourne, and then again at both the Los Angeles and Amsterdam ALMS conferences; he is participating in my Migrating Archives project.

How did your collaboration begin with John Q? What have been the results of that collaboration?

It was indirect through San Francisco artist Rudy Lemcke, a friend who had been corresponding with Joey Orr for a few years. The focus of both John Q and my work on activating queer archives lead Rudy to make virtual introductions, which in turn brought John Q to San Francisco to do research but also so that the five of us (three John Q members Rudy and me) could brainstorm some form of collaboration. The idea of collaborating came up almost right away, sight unseen! It mostly unfolded through email, focused very loosely on the idea of exchange of archives, archive migration, and the notion that we can not only take information from the archive, but can add to it and alter it.

The first stage of our collaboration involved John Q sending a box of artifacts to Rudy and me based on archives they had researched from the Atlanta History Center. In a panel discussion performance at the GLBT History Museum, John Q unfolded the narrative behind these objects, while Rudy and I introduced two archives from SF that would later become “guests” in Atlanta. One of these was the archive of Crawford Barton who had actually immigrated to SF from Atlanta in the 1960’s.

Four and a half months later I was on a plane to Atlanta (with new participant in the collaboration, Barbara McBane) having shipped a box of artifacts previously to John Q which they had opened publically in front of an audience. At the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, John Q, Barbara and I presented this new phase of the Atlanta-SF archive exchange, introducing new material from Crawford Barton’s archive and the archive of transgender woman Veronica Friedman that I had previously matched Barbara to as part of the LINEAGE matchmaking project.

I would say that the collaboration is pretty relaxed right now, and I’m not sure what the next stage will be. But the relationships are still evolving with idea exchanges and mutual support, so I imagine we’ll do something together again. I hope so.

In conclusion, how is your residency at the GLBTHS shaping your practice?

As an artist, LINEAGE has expanded the possibilities for my art practice. I am collaborating with a non-profit organization that initially was very cautious about having an “artist-in-residence.” As a kind of ambassador from the arts, this project has expanded their understanding of what art can be and do. Each event linked to LINEAGE has brought new crowds of people to the Historical Society. While no one is yet rushing to make a major donation (I’ve raised my own funding), my hope is to attract an endowment for an ongoing Artist-in-Residence program.

LINEAGE provides one model for how to bring archives, our history, off the archive shelf into creative visibility. In this process, desire crosses time, crosses into and out from the archive, lurks in liminal spaces between life and death, between beginnings and endings. Personal archives arouse all kinds of prurient curiosities, inappropriate speculations and impossible longings—perfect provocation for art that inscribes LGBT history in new ways.[1]

[1] Some text taken from an unpublished paper given at the College Art Association annual meeting, 2010.

1 comment