A color-blind Stockholm syndrome

09 March 2016 – Jason Allen

art, race, The Public Historian, TPH 38.1, "Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton" responses

“George Washington as Farmer at Mount Vernon,” 1851, part of a series on George Washington by Junius Brutus Stearns. Located at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The American narrative, like any cultural narrative, consists of stories that structure and assign meaning to the nation’s origin, history, and existence. In theory, this narrative can link Americans who have experienced genocide, slavery, and white privilege. But for people descended from enslaved peoples, this narrative has instead been used to conceal the inconvenient truths of systemic historic and current racial injustice and inequality.

The realities of past and present-day racism and inequality make absurd the notion of an egalitarian, color-blind, post-racial American society. The narrative of a color-blind America requires removing the victims of race-based injustice or, at least, implies that black and brown lives, along with their claims of systemic racial inequality, no longer matter. Peoples of color have the option of reinterpreting themselves and their American origin stories through the white American narrative. The musical Hamilton triumphs in this reinterpretation. It is a product of a white American cultural narrative disguised as a unifying color-blind narrative that reaffirms a supposedly shared origin myth.

In her review of Hamilton, “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past,” Lyra Monteiro points out that the musical’s actors were cast not in spite of, but because of, their color. That this casting compels these actors of color to separate themselves from their African American histories is evident from their own comments about the play. Monteiro quotes Christopher Jackson (George Washington) as noting that the show’s predominately white audiences do not want to be “preached to” about slavery, and Leslie Odom Jr. (Aaron Burr) hopes that people of color who see the play will “feel a part of something that [they] don’t often feel a part of.” These actors acknowledge the color-blind ethos and strive not to offend white American myths of freedom and equality, but they must subjugate the moral and physical struggle of peoples of color to do so. Color blindness can offer people of color acceptance; in this case, the African American actors in Hamilton are rewarded for minimizing the lives and struggles of peoples of color and thus erasing the active agency of freedom-seeking African Americans and the shame of a nation built on human trafficking. The lure of color blindness can blind people of color to their complicity in erasing or minimizing the histories and memories of their ancestors.

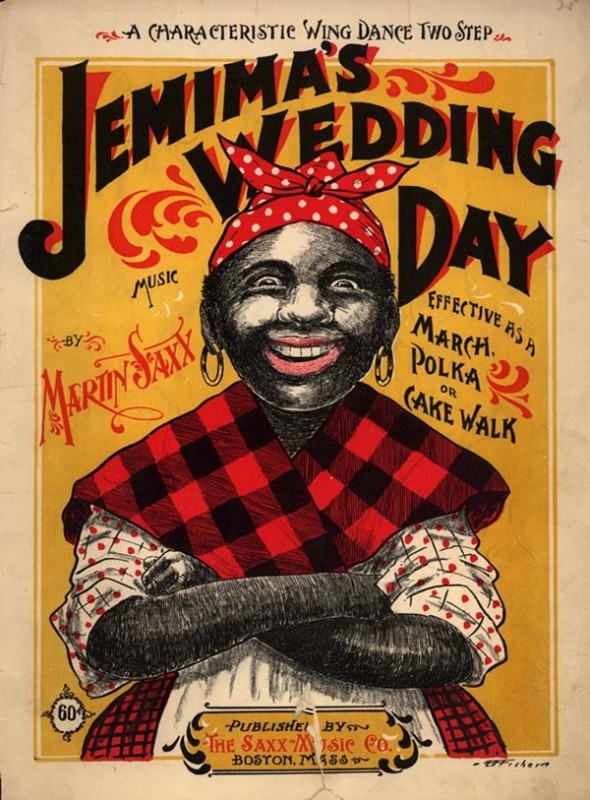

“Jemima’s Wedding Day,” 1899 sheet music cover. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

We can see this, also, in the children’s book, A Birthday Cake for George Washington, which was recently recalled by its publisher, Scholastic, in response to criticism of the book’s depiction of slavery. In its portrayal of Hercules and his daughter Delia, who were two African Americans enslaved by President George Washington, author Ramin Ganeshram and illustrator Vanessa Brantley-Newton, both women of color, decouple the founders and foundation of the United States from racism and slavery. Hercules and Delia smile while working like the shamelessly racist depictions of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben. According to Brantley-Newton, her “research indicates that Hercules and other servants in George Washington’s kitchens took great pride in their ability to cook for a man of such stature. This is why [she] depicted them as happy people.” The high status of a life-long human trafficker supposedly raises the stature of the work of these enslaved “servants” in the minds of the fictional enslaved and lessens the injustice for the reader. Hercules’s apparent pride in his ability to cook for a man of “such stature,” however, did not stop the real Hercules from escaping captivity and claiming his freedom in 1797.

Both A Birthday Cake for George Washington and Hamilton minimize the kidnapping, torture, and abuse of enslaved Africans and their descendants. Dr. Monteiro points out that the actors in Hamilton “consciously refer to the shaping of historical memory throughout the play.” A Birthday Cake for George Washington attempts the same sleight of hand. Both, authored by people of color, present American history in a way that absolves the founders and the system of government they established from the crime of human trafficking.

Ignoring race is a convenient option for many white Americans and an expensive one for peoples of color. For white Americans, color blindness shields them from dealing with the intractable plague of racism and with the role race plays in inequality. People of color, on the other hand, can re-cast themselves as untouched by the tags of inferiority and inequality by minimizing the terror committed upon their ancestors and the role slavery has played in persistent discrimination. Color blindness seems to offer a respite from being pigeonholed, haunted, and separated by race.

Hamilton’s cheerleaders take great pride in the ability of the powerbrokers of a slave nation to provide inspiration to and connection with peoples of color. Hamilton, by design, does not challenge but reaffirms the American exceptionalism that casts the founders of a nation built on slavery and racism as freedom fighters. In casting the descendants of enslaved people as the founders, the musical integrates faces of color without burdening the audience with the baggage of racism and obscures slavery’s centrality to the origin of the United States.

Hamilton is an American immigrant story written by a descendant of the survivors of genocide in the Caribbean, kidnapping from Africa, and enslavement in the Americas. Monteiro suggests that though Hamilton integrates the physical bodies of people of color, the historic and present injustices against peoples of color are largely ignored so as not to threaten its feel-good underpinnings. Hamilton and A Birthday for George Washington each attempt to redefine the historical relationship between human traffickers and enslaved people. But while the descendants of enslaved people should not be forced to define themselves solely by the status of their ancestors, when color blindness leads to the erasure of past and current struggles of peoples of color against injustice, we must remind ourselves that Hamilton–and A Birthday Cake for George Washington–are escapist historical fiction, not history.

~ Jason E. Allen is the director of community engagement at the New Jersey Council for the Humanities. Previously, he was executive director of the Richard Allen museum at Mother Bethel A.M.E. in Philadelphia. He is a museum and non-profit consultant, specializing in exhibitions, programming, community engagement and development for his company, ABCDEdu, where he works with arts, culture, and heritage organizations seeking to engage underserved and underrepresented communities, histories, and memories. Jason serves on the boards of Historians Against Slavery and the New Jersey Association of Museums.

Editor’s note: In “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton,” published in The Public Historian (38.1), Lyra Monteiro asks, “Is this the history that we most want black and brown youth to connect with–one in which black lives so clearly do not matter?” This is the second of four posts (first post here) that will be published by The Public Historian responding to Monteiro’s review.