A Public Historian in Publishing: Lessons from Working Outside the Field

11 February 2021 – Danielle Lehr Schagrin

As we grapple with the short-term (and potentially long-term) impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis on museums and cultural institutions, public historians across the field are dealing with layoffs, staff reductions, and decreased funding. And when non-history job prospects arise, offering higher salaries, healthcare benefits, and the ability to work from home, many face a difficult choice: to hold out for a position in public history or pursue opportunities in a different field. What advice can we offer our colleagues who have left the field? And which hiring practices should public history employers revisit in order to address the particular challenges and inequities of this moment?

Having once made the difficult decision to leave public history, I empathize with my colleagues who face the same choice in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Two years ago, my husband and I decided to move so he could accept an exciting job offer. I ended my four-year tenure as an education program coordinator for a historic house museum and looked forward to the next phase of my career in a new place. After a few unsuccessful museum interviews, I came across a job advertisement that piqued my interest—an editorial assistant for Woodcarving Illustrated magazine.

A publishing skill like photography is transferrable to curatorial work, marketing, and other museum jobs. Chip-carved box by Marty Leenhouts. Photo credit: Fox Chapel Publishing.

I was intrigued by the position, but it was not exactly the upward career move I envisioned. I dedicated years of study to public history, earned a Master’s degree in the field, completed a dream internship for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and established myself as a museum professional. I was not enthused about the idea of starting over in a new field.

A flood of questions rushed through my head. “Will I ever get back into a museum role? Will future employers wonder why I went from a ‘coordinator’ to an ‘assistant?’ Can I still call myself a public historian?” When it came down to making a decision, I accepted the job for two reasons: First, we needed the income. Second, I hoped to acquire a new skillset that would help me if or when I returned to public history.

Two years and another move later, I was able to leverage my experience in the publishing field and return to the history field as a writer and researcher for two historic house museums. I hope the following lessons I learned during my time away from the field will offer some clarity for those who hope to return to the public history field.

- Work on hard skills. As an editorial assistant for the magazine, I spent much of my time making text edits and formatting changes to magazine articles in Adobe InDesign. Coming from a museum with a limited budget and no access to the Adobe Creative Cloud, this was a golden opportunity to learn new software skills. As I learned the basics from the art director and more experienced editors, I thought about all the practical applications in the museum world: brochures, exhibit catalogs, annual reports, and more. The same principle applies to a plethora of hard skills. Picking up a new digital tool could help you land a digital humanities position. Budget-balancing skills might catch the eye of a museum hiring committee in search of a financially-minded executive director. Social-media savvy could be desirable to the small historical society looking to expand its audience. Find a transferable skill and own it!

- Use your public history training where you are. In a post on the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment, Daniel Vivian pointed out that a number of survey respondents discussed the utility of their public history training in their non-public history positions. While I came to Woodcarving Illustrated with very little knowledge of carving knives and gouges, I was ready to employ my public historian’s toolkit. I knew how to write and edit engaging communications pieces. I drew on my oral history experience when I interviewed artists for feature articles. I was experienced in public speaking and represented the magazine at carving shows. I felt comfortable handling, photographing, and documenting carvings for publication. The public historian in me was not dormant—she was active and using her skills every day.

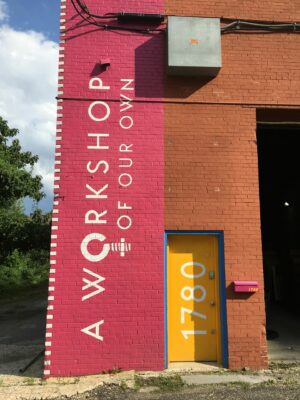

I drew upon my oral history training and appreciation for material culture when I wrote an article on A Workshop of Our Own, a workshop for women and gender non-conforming craftspeople in Baltimore, MD

- Stay connected. When I started in museums, I relied on my colleagues to share interesting articles and provide stimulating conversation, keeping me in touch with trends across the field. While my magazine colleagues were equally passionate about their areas of expertise, during my time at the magazine, I was responsible for keeping myself connected to the public history field. After evaluating my schedule and budget, I joined the NCPH and the American Association for State and Local History, and I attended one day of the 2019 AASLH conference in Philadelphia (which was within driving distance). I also started following more historians on Instagram and looked forward to the NCPH takeover each week. While I experienced FOMO (fear of missing out) and felt pangs of jealousy when I read about the impactful work being done in museums and archives, I also felt invigorated and inspired. Staying connected requires effort, and it can sometimes be painful. But staying abreast of news and developments in the field will keep your history senses sharp and might lead to job opportunities.

- Don’t sell yourself short. When I attended the 2019 AASLH Conference in Philadelphia, I felt self-conscious and nervous. I prepared for the inevitable questions and feared that my colleagues would react to my career change with pity. But the response was not what I expected; instead of condescension and disinterest, most people reacted to my job with curiosity and excitement. When I started interviewing for public history jobs again, I resolved to focus on my accomplishments rather than apologize for my time away from the history field. I explained how my newly acquired skillset would benefit my prospective employers and updated my portfolio to include my recent feature articles. Each prospective employer responded to my magazine experience with enthusiasm.

Now is the time for public historians to embrace all of their skills, whether they acquired them in history jobs or other positions. But it is also time for history employers to revisit hiring practices and prepare hiring committees to evaluate applications differently in the wake of COVID-19. If you are involved in the hiring process for your museum or cultural institution, take the following suggestions into account:

- Consider applicants with relevant experience who are coming from non-history jobs. They could bring useful skills, advantageous partnerships, and fresh perspectives.

- Talk with your Board of Directors/hiring committee about the inequities of COVID-19 job losses and recovery, which disproportionately impact women, people of color, and disabled people. Don’t count someone out because of a gap on their resume.

- Stop asking applicants for their salary history. This discriminatory practice will be especially harmful to those who sustained pay cuts during the pandemic.

- Start listing a salary or another measure of compensation on your job postings. This ethical practice is also a time-saver for employers and applicants.

Public historians are trained to act with creativity, empathy, and open-mindedness. Let’s employ those traits to support our colleagues in non-public history fields and work toward more ethical, inclusive hiring practices.

~Danielle Lehr Schagrin is a writer, editor, and public historian in the Philadelphia area. In addition to her journey into the world of woodcarving and magazines, she has worked for such museums and non-profits as Pennsbury Manor (Morrisville, PA), The Grundy Museum (Bristol, PA), and Cranaleith Spiritual Center (Philadelphia, PA).