Abiding Time

18 August 2020 – James F. Brooks

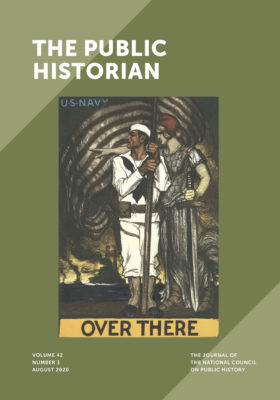

The cover of the August 2020 issue of “The Public Historian” features a WWI poster of Columbia directing a sailor with an outstretched arm, c. 1917. Poster by Albert Sterner and held in the collections of the University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections

Editor’s note: We publish The Public Historian editor James F. Brooks’s introduction to the August 2020 issue of The Public Historian here. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members and to others with subscription access.

There seems no better time to abide in the message of past-president Marla Miller’s fortieth-anniversary address than our present. Her gracefully crafted message, drawing upon Rebecca Solnit’s notion that “hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act” resonates all-too-well in our current moment.[1] Some six months into the global outbreak of COVID-19 at this writing, more than ten million infected, over half a million dead, and no clear end in sight, we at the TPH offices brought two issues to print without once being closer than a Skype call or Zoom meeting. So, too, have we chanted the names of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor with so many of our neighbors. We are all, as Miller writes, “planting seeds and laying groundwork” for whatever future lies ahead, and in the optimism of pessimists, to paraphrase Solnit, know full well that without our conscious daily action, things can only get worse. May we abide in deeds, however small, that might yet yield a world closer to our dreams.

Sergey Saluschev and Kalina Yamboliev bring us their comparative analysis of two sites of public historical interpretation: the Stalin Museum of Gori and the Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi, Georgia. Neither museum is without an investment in protecting the reputation of their most famous native Georgian son, Josef Vissarionovich Jughashvil, especially in terms of the current nation’s desire to be seen as historically significant to western European history and thereby deserving of at least nominal membership in that community. Yet the two museums also represent tensions between the local and the national, and the extent to which Georgian identity “depends deeply on the embrace, disdain, or ambivalence toward the Stalinist era.”

We continue with Magdalena Saryusz-Wolska’s penetrating critique of ways the right-wing press in Poland manipulates historical imagery to fan the embers of xenophobia and nationalism in their mainstream magazines’ covers. The 2015 victory of the nationalist PiS Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość; in English, Law and Justice) seems to have emboldened all forms of media. But Saryusz-Wolska’s focus on visual culture shows it particularly vulnerable to manipulation through the redeployment of historical images, such as those of the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, suggesting that today’s refugees are simply another agent of conquest. Her particular interest is in the dialectic between authors, editors, and designers, on the one hand, and viewers, readers, and consumers, on the other, since such imagery operates in a dynamic not unlike producers and consumers of public history. She finds that the deployment of manipulated historic imagery, especially in fanciful reimaginings around Poland’s (nearly) successful defense of its border against Germany, reinforces what Zygmunt Bauman terms “retrotopia,” or a longing for a past that never existed.

Three “Reports from the Field” provide the core of the issue, with Joseph Plaster’s account of his experience as director of the “Polk Street: Lives in Transition” oral history project in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. Drawing on more than seventy oral histories from this historically working-class and queer district that trace its transformation in recent years into a dining and entertainment hub for the city’s tech elite, he shows that history on the edge of erasure proved salvageable and in turn energized counter-narratives. In the end, the project “provided platforms for vulnerable populations to assert their own identity and insist on the existence of their own history; it challenged homophobic definitions of ‘safety’ and ‘family’ by publicizing counter-narratives from queer residents; and it fostered dialogue and a relative degree of cooperation among groups competing for urban space.”

Jesse Ohl brings us his reflections on an exhibit of World War I posters in the collections of the University of Alabama, mounted in 2018 in recognition of the centennial of the Great War. Featuring an unusual interpretive emphasis on the artistic composition, or visual rhetoric, of the posters, the exhibit offered visitors a more reflective experience than many such, which required they engage more deeply with the surface imagery “to attend to the language of the visual” and thereby to understand how the artists created the “story” embedded in the final composition. Ohl’s curatorial emphasis is on the effective power of artistic imagery, noting that while “emotional reactions are personal, they can also be shared,” so he designed the exhibit to offer a method “through which the rhetorical elements of poster propaganda achieve greater clarity and scrutiny.”

On a personal note, our closing piece, Marcelle Wilson’s “Sparking Memories: Memory Tourism for a New Audience,” is particularly meaningful to me, in that I tried to support my mother’s fall into the abyss of Alzheimer’s, which ended in 2014. The Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor, managed by Youngstown State University’s history department, has increased museum visitation through an innovative program welcoming those suffering from dementia. Reading Wilson’s submission reminded me that although there came a time when my mother could not distinguish me from her memories of my brothers, or my father, for that matter, she retained a keen grasp of her childhood and her lifetime dedication to raising Morgan horses on our ranch west of Boulder, Colorado. So too, with many of the former steel-workers and family members in the now-deindustrializing city. Youngstown museum personnel found visitors excited to see tools, protective gear, and processes on display that remain sharp in their memories, empowering at a moment when memory loss can be so disheartening. Wilson concludes by citing research that shows such moments have a positive afterglow, in “improved sleep, better mood, and less agitation.”

These qualities are, of course, just the simple pleasures that we all need right now, to abide in the “spaciousness of uncertainties” that lie ahead.

~James F. Brooks is editor of The Public Historian, the Gable Distinguished Chair of History, University of Georgia, and Research Professor in History and Anthropology, UC Santa Barbara.

[1] Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities, 3rd edition (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016), xiv.