An uneasy fit: History in historic preservation

03 February 2015 – Liz Almlie

The Public Historian, historic preservation, National Historic Preservation Act, National Historic Preservation Act commemoration

The FBI Headquarters Building in Washington, DC, is an example of Brutalist architecture that is under scrutiny to determine if it should be saved. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Editor’s note: This post continues a series commemorating the anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act by examining a past article published in The Public Historian, describing its significance, and relating it to contemporary conversations in historic preservation.

Eleven years after earning a 1966 PhD in history from Washington State University, J. Meredith Neil arrived to work as the first historian hired to the relatively large staff of Seattle’s historic preservation office. He pulled strongly from his experience, and I’d dare say frustrations, in that new role for his 1980 article for The Public Historian, “Is There a Historian in the House? The Curious Case of Historic Preservation.” Neil argued that historians needed to be involved in preservation to prove that history was relevant, democratic, and as important as aesthetic or economic claims for preservation. From South Carolina’s equalization schools to Brutalist architecture, history has been successfully used to argue for the preservation of places that may not have initially been appealing for reasons of architecture or economics. Working for a State Historic Preservation Office, I have also seen that, while history and preservation often intersect, they do not always share motivations, people, or goals. The engagement of historians in preservation is critical, but the best preservation successes happen with a diverse network of support.

As postwar development made rapid and jarring changes to the built environment of American cities, supporters of the preservation movement sought a national and systematic way to prioritize and protect historic places, from which came the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act. The professionalization of preservation developed quickly to meet the demand created by the NHPA. Neil argues that preservation was first implemented by planners and architects because they were used to working within regulatory systems, while historians coming out of academia were becoming professors or librarians. Neil saw a desperate need for “historians who believe that active involvement in public issues is as fulfilling as the teaching of class or the writing of scholarly papers.” (38) He wanted historians to be trained and able to work with planners and architects to navigate the same systems so that “historic significance,” which had been codified into the National Register of Historic Places, would have real meaning within preservation. Neil hoped that more historians would find public service fulfilling and have access to preservation training. Indeed, the numbers of public historians and traditional historians working on publicly engaged projects have grown steadily over the last couple decades.

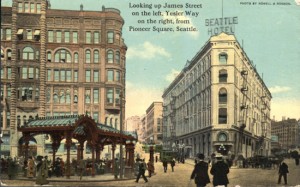

This historic postcard of Pioneer Square shows both large signs and metal fire escapes. Photo credit: City of Seattle archives

To Neil in the late 1970s, the predominance of aesthetic and economic-based preservation could too easily produce historic places that were “artificially extracted from their context.” (34) Although Neil mentions that some preservation plans, like those for the Vieux Carré in New Orleans and for the City of Charleston (South Carolina), prioritized historical continuity, he worried that too many preservation efforts would freeze a place in time and effectively work against history. People who might be generalized as “aesthetic” preservationists were fighting for things that historians considered minutiae, like the retention of obsolete metal fire escapes or anachronistically small signs in the example of Seattle’s Pioneer Square that he cites. Still today, aesthetics, economics, and history clash as we debate the design of new alley-facing garages in historic districts, the eligibility of 1950s modernized storefronts, the fate of “tin-can” water towers that cities have determined to be functionally obsolete, the street-appeal of a Craftsman porch on a small Colonial house, and the economic viability of a vacant rural church. When advocating for preservation in fragile funding and political environments, champions are sought among developers, Main Street advocates, and those in heritage tourism. Profitable re-use can be argued to decision-makers who might think of historical significance as an amenity. Historic materials or craftsmanship are often up for sacrifice when restoration affects the profit margin (real or perceived). Although history and storytelling can be effective for advocacy amidst the general public, history often takes a backseat when making the deal.

Interior view of the Gettysburg Cyclorama in the former Neutra building location. Photo credit: Library of Congress

On the other hand, trends toward breadth and diversity have seemed to be mutually supportive between history and preservation. For example, the history of postwar and modernist buildings and landscapes seems to be finding a passionate following. High-profile cases, like the demolitions of the Cyclorama building at Gettysburg National Park and Prentice Hospital in Chicago or ongoing efforts for the Miami Marine Stadium, Peavey Plaza in Minneapolis, or the Orange County Government Center in Goshen, NY, have raised the profile of the Recent Past architecture and modernist architects, but disagreements persist among preservationists (let alone the general public) about what is worthy of limited time and resources. When the aesthetics of modernist or industrial architecture are questioned, how do you advocate for the history of buildings that some people consider ugly? How hard do you fight and who is willing to fight when funding or political support is absent or even stacked in opposition?

To successfully preserve a historic place, you have to find at least one viable vision for the future of that place and persist in building the support that will make that future a reality. Many of us are trying to develop skill sets and bases of knowledge so that we can build strong preservation networks of historians, planners, architects, landscapers, realtors, developers, craftspeople, bureaucrats, technology experts, technical conservationists, tourism coordinators, historic site managers… (deep breath)… who can all play important roles in saving historic places for memory, education, tourism, neighborhood revitalization, economic development, sustainability, smart growth, and so on. Preservation is increasingly diverse. These groups will not always share one vision. They will often honestly (and vehemently) disagree. Historians need to be at the table if it’s history that we want to preserve. The key will be to continue to learn from and communicate with each other as we go so that we can find balanced solutions that work.

~ Liz Almlie has worked as a regional Historic Preservation Specialist for the South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office since 2011. She received her MA in Public History and a Certificate in Cultural Resource Management & Historical Archaeology from the University of South Carolina, Columbia in 2010.

1 comment