Archiving COVID-19: An Undergraduate Public History Project

05 October 2020 – Elias Levey-Swain and McLain Sidmore

Historians for Hire is a civic engagement course at Carleton College that partners students with local public history projects. It seeks to illuminate the value of community involvement in the history curriculum and elicit student reflection on the significance of their work as aspiring historians. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and our spring trimester moved online, Professor Susannah Ottaway invited us to turn this seminar into a collective effort to document, preserve, and analyze our present moment. We put our intended projects aside, turning our efforts toward constructing and curating a digital, Carleton-specific COVID-19 archive inspired by the Journal of the Plague Year (JOTPY) project. This allowed us to create a collaborative space where we gained practical and theoretical knowledge about the creation of an ethical archive, while also engaging with a national initiative by contributing to the larger JOTPY project. It likewise helped us process the upheaval of our extraordinary spring trimester, demonstrating how our vastly different perspectives shaped the archive we created.

Screenshot of the Carleton Covid-19 Archive.

Our archive was built on an Omeka platform, and we—the students, supported by a fifth-year digital humanities specialist, Elizabeth Budd—became principal editors. We encouraged contributions from anyone in our college community. Groups of students in the class collected sources around a number of different themes and in many different forms, from interviewing students quarantined on campus to conducting extensive outreach to explore disproportionate impacts on various communities, particularly across race, age, and geography. Many focused on their home communities across the country and the world, interviewing neighbors, clipping news stories, and submitting photos of what their towns and cities looked like amidst a global pandemic. Eight students continued to work on the archive over the summer, tagging items and creating and revising exhibits and collections.

Documenting the origins, spread, and cultural significance of an evolving and dynamic public health emergency proved a daunting challenge on top of an undergraduate experience that already felt like it was moving at double speed. The usual uncertainties that plague the lives of undergraduates have this year been folded into a hideous dish of travel restrictions, economic distress, health concerns, and more. For undergraduate archivists, this has been served up with an added question: how to preserve an authentic glimpse of this chaos for historians of the future?

After reading the National Council on Public History (NCPH) and American Historical Association (AHA) guidelines for the ethical practice of public history and reflecting on relevant readings from previous coursework, we realized that archives cannot include everything, and that omissions tend to be drawn along lines of race, class, gender, and other historically unjust categorizations. With this understanding, we sought to turn an archive at our privileged institution into an inclusive digital space, preserving diverse histories from within and beyond our immediate college community. Our efforts ranged from focusing on experiences of displacement, to using age as a category of analysis, to considering how public spaces shared across different social groups have evolved in dynamic ways. We ultimately did not create the perfectly diverse and inclusive archive that we had envisioned. But we understand this not so much as a failure but as a reason to keep theorizing about how archives can preserve the histories of diverse communities.

Over time, we encountered an urgency not merely to expand the voices recorded in our archive but also to capture the emotional complexity and immediacy of the moment. We wanted to convey the chaos, fear, and uncertainty of this period. In this vein, we prioritized detailed reflection as a tool to document and preserve the peculiar limitations and anxieties that informed our collecting choices. Through personal journals, class discussions, and a reflective WordPress blog, we turned our critical gazes–long trained to focus on assigned texts and primary sources–onto ourselves. We needed to think like future researchers viewing our archive without our experienced eyes. It became essential for us to convey in the archive the constraints enforced by social distancing, spotty internet, and a profound fear of taking resources—even time or energy—from those fighting the pandemic. Some reflections were preserved in the archive itself, where our peers and other community members elected to contribute their ongoing “pandemic journals,” offering insight into their own concerns during this period. Other personal and group reflections were preserved on our public-facing WordPress blog, clarifying our concerns and choices as a means of contextualizing the archive for future users.

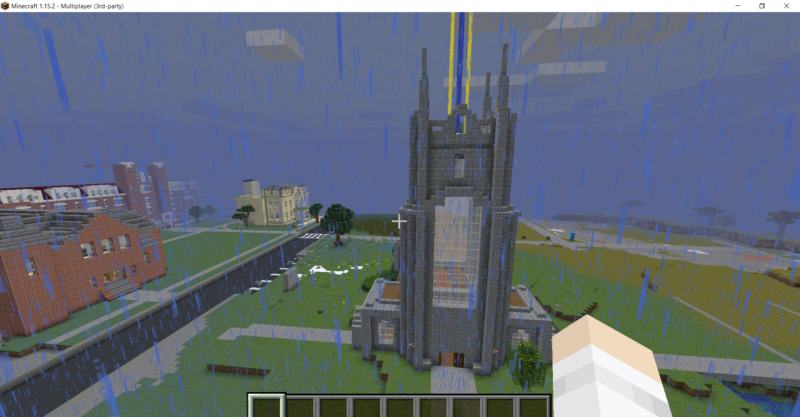

This is a depiction of the Carleton Minecraft server that students used to digitally recreate the college’s campus during their spring trimester. This recreation is now part of the Carleton Covid-19 Archive.

These anxieties led to discussions and questions about what was appropriate to document and the historical power of our curatorial choices. Difficult debates, such as the merits of representing the positive—even humorous—aspects of the moment emerged. In this time when everything seemed so consequential, items reflecting connection and beauty lifted us up; yet this content was pitted against a fear of not documenting the injustices and suffering that also marked this period. These are not easy conundrums, and the opportunity to look deeply at the process of historical creation, with all its uncertainties and biases, required each of us to face archival production and research in a new and challenging way. It forced us to unpack and reconsider dichotomies between historical records and lived experiences, and the messily interwoven relationships between those who live history and those who document it.

Carleton’s Covid-19 Archive offers only a small window into the experiences of students, faculty, and their communities during the pandemic, and it certainly has other shortcomings. Yet it speaks to the potential impacts of public history within an undergraduate history education. The gross inequalities laid bare by Covid-19 remind us daily of the incredible need for universal access to diverse and challenging history education that responds to contemporary issues and challenges us to reexamine the past—and present—from numerous perspectives. It is imperative that colleges instruct students in the practice of true community-centered history, allowing us to wrestle with the implications of our historical inquiries. Experience in archival production and community-partnered history offers us practical public history skills and tools for future employment. It also forces us to think reflectively about our own work within a community, to judge scholarship by its service to our communities, and to envision historians as links between the past and the present. Moreover, for those of us taught to think of history as an academic subject only, this work redefines history as a form of labor with both theoretical and real-world implications.

As the national reckoning over police violence and systemic racism continues, there is an increasing demand for historians, teachers, and citizens to embrace more inclusive, dynamic, and complicated histories. Public history, at its best, widens the scope of historical inquiry, gives diverse communities the power to tell their own stories and inspire their younger generations, and deconstructs the truth of the past with an eye toward building the future. These are lofty goals for a short-term undergraduate project, and we by no means achieved them all. Yet students are stakeholders in diverse communities; and their curiosity and drive to create a better future represent a tremendous opportunity to embrace the aspirations of public history. All we need is a chance to practice.

The authors would like to thank their peers Jacob Bronsky, Rebecca Hicks, Sam Kwait-Spitzer, Margaret Lachman, Natalie Lafferty, Marcella Lees, Anne Lim, Miyuki Mihira, Clara Posner, Michael Schultz, and Carolyn Wood, Hannah Zhukovsky and their professor, Susannah Ottaway, Elizabeth Budd, and Katy Kole de Peralta of Arizona State University’s JOTPY archive for her visit to our class.

~Elias Levey-Swain is a senior at Carleton College studying global and imperial history. He will be pursuing programs for continued study in history after graduation, with aspirations of becoming a professor.

~McLain Sidmore is a senior at Carleton College studying U.S. and environmental history. She hopes to pursue a career in secondary history education.