Atlanta: Immigrant gateway of the globalized South

19 February 2020 – Kathryn E. Wilson

community history, sense of place, government, Immigration, 2020 annual meeting, Atlanta Series 2020, demographics

Buford Highway, 2015. Photo credit: Marian Liou

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a series of posts from members of the Local Arrangements Committee for the NCPH 2020 annual meeting which will take place from March 18 through March 21 in Atlanta, Georgia.

You may be surprised to learn that one of the largest Hindu temples in the United States is located just outside Atlanta, and that the city is home to the second-largest Bhutanese community in the country. Atlanta’s transformations in the last few decades have made it a major immigrant destination in the Southeast, ranked as an important “emerging gateway” for newcomers in the twenty-first century.[1] In 2015, the Pew Research Center placed Atlanta in the top ten cities for Burmese, Nepalese, Sri Lankan, Vietnamese, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Indian populations.[2] Atlanta is also home to the fastest increasing Latinx population in the country (growing 118% between 2000 and 2010) and Georgia is one of the top ten states for Latinx immigration growth.[3]

Chinese New Year celebration at China Town Mall, 2015. Photo credit: Kate Wilson

Since the passage of the Hart Celler Act in 1965, which reversed national origin quotas, Atlanta’s immigrant population has grown, particularly in the last two decades. What accounts for this change? Economic growth in the Sunbelt South during the 1990s drew immigrants to expanding technology, construction, health, and service sectors.[4] The Atlanta area was designated a center for refugee resettlement in the late 1980s, and embraced a new image as an international city after hosting the Olympics in 1996.[5] During the 1990s, Atlanta’s foreign-born population more than doubled from 4% to 10%. By 2010 it had tripled, and in 2016 immigrants comprised 13.7% of the metropolitan area’s population.[6]

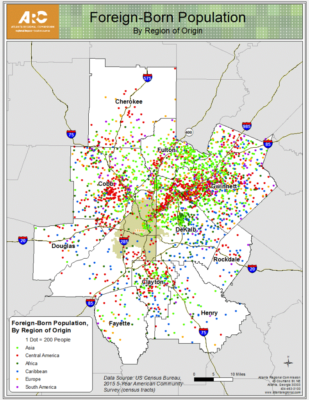

Foreign-born population of Atlanta by region of origin. Map Credit: Atlanta Regional Commission, used with permission.

Atlanta embodies the demographics and geography of recent immigration to the US. In greater Atlanta, 95% of immigrants are found outside the city, in suburban counties to the northeast, northwest, and south.[7] Towns like Chamblee, Doraville, Norcross, and Duluth have been transformed into majority-minority municipalities by Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Caribbean, Mexican, Central American, and African communities.[8] Representing and connecting this new immigrant geography is Buford Highway, a six-lane thoroughfare heading 20 miles northeast out of the city through DeKalb and Gwinnett Counties. Once a nondescript local road bordered by strip malls, fast food joints, and tire stores, today Buford Highway is a central corridor for 1,000 ethnic businesses representing 21 nations (housed in landmarks such as Plaza Fiesta, the Buford Highway Farmer’s Market, and China Town Mall, as well as immigrant organizations like the Center for Pan Asian Community Services and the Latin American Association.[9]

Much of Atlanta’s diversity is due to over three decades of refugee resettlement. Vietnamese, Cambodian, Ethiopian, and Eritrean refugees were the earliest refugees formally brought to Atlanta as part of the international resettlement program and have formed enduring communities.[10] Since then and until 2017, Georgia welcomed 2,000 to 3,000 newly-arriving refugees each year.[11] Many of these refugees settled in and around the town of Clarkston, roughly 10 miles from downtown Atlanta and known as the “Ellis Island of the South” and the “most diverse square mile in America.”[12] Clarkston’s population reflects current and historic refugee flows: it is currently home to African (Somali, Eritrean, Ethiopian, Sudanese), Asian (Bhutanese, Burmese, Cambodian) and, most recently, Syrian and Congolese arrivals. Businesses in Clarkston along Market Street, Ponce de Leon Ave, and Montreal Road include Nepali, Burmese, Ethiopian, and halal restaurants, Asian and Ethiopian groceries, and a Thriftown which has stayed in business for 25 years by catering to the refugee communities’ needs.[13]

On June 30, 2018, anti-ICE protesters gathered outside the Atlanta Detention Center and marched down Martin Luther King Drive to the Richard B. Russell Federal Building. Photo credit: Kate Wilson

While immigrants make a positive contribution to the regional economy, they also face numerous challenges. Immigrants often work in the most dangerous and difficult occupations, such as the poultry industry, and the undocumented are particularly vulnerable to exploitation and police profiling. Traveling on foot or by bicycle on Buford Highway can be dangerous.[14] Immigrants face backlash in historically white communities and in 2011 the Georgia state legislature passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act, one of the most draconian immigration laws in the country. Since 2017, Atlanta has also been a focus of ongoing high-profile raids by ICE targeting undocumented migrants, though the city recently ended its cooperation with that agency.[15] However, two and a half hours southwest of the city, in Lumpkin County, the Stewart Detention Center continues to be the object of protests against detainee conditions.[16] El Refugio is one organization through which Atlantans offer support to detainees and their families.

In 2006, Atlanta was a major site of immigrant rights protests and the city has remained a center of activism for immigrant rights. Recognizing the importance of immigration to the local economy and culture, Kasim Reed created the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs in 2015 to make Atlanta a Welcoming City, later spreading this effort in the larger metro area through its One Region initiative. Today, organizations such as the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR) form coalitions with African American activists to protest ICE actions and help those facing deportation.

World Refugee Day at Refuge Coffee, Clarkston, Georgia, June 20, 2019. Photo credit: Joseph McBrayer/Coalition of Refugee Service Agencies (CRSA)

Immigrants and refugees in Atlanta have undeniably contributed to historic changes transforming the racial, economic, and cultural landscape of Atlanta and by extension the southeast U.S. Public historians are positioned to document these changes and include immigrant communities in the interpretation of Atlanta’s story. The Atlanta History Center has recently begun collaborating with immigrant communities as part of its “Gatheround: Stories of Atlanta” exhibit and neighborhood initiative.[17] A recent project involved working with the Plaza Fiesta, the Latin American Association, Freedom University, and the Latino Community Fund to create a public art piece. An upcoming project will focus on Clarkston.[18] We Love BuHi is an organization devoted to documenting and forging community along Buford Highway through special events, creative placemaking, marketing, and an oral history project. Green Card Youth Voices recently gathered thirty area high school students to share their immigrant experience in a publication and exhibit. To learn more about these projects, and the issues surrounding the interpretation of immigrant experience in Atlanta, attend the roundtable at the annual meeting, “Threading Immigrant Stories: Reweaving the Fabric of Southern Heritage,” Friday, March 20, at 8:30 a.m.-10:00 a.m.

~Kate Wilson is an associate professor of history at Georgia State University where she teaches public history, oral history, and material culture. For more information, visit: https://history.gsu.edu/profile/kathryn-wilson-3/

[1] Audrey Singer, Susan W. Hardwick, and Caroline B. Bretell, eds. Twenty-First Century Gateways: Immigrant Incorporation in Suburban America (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2008); Audrey Singer, “The Rise of New Immigrant Gateways,” Brookings Institution (February 2004), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/20040301_gateways.pdf.

[2] Atlanta is ranked 5th for Burmese, 7th for Nepalese, 8th for Sri Lankan, 9th for Vietnamese and Bangladeshi, and 10th for Pakistani and Indian populations, Pew Research Center, Social and Demographic Trends, 2017, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/chart/top-10-u-s-metropolitan-areas-by-nepalese-population/.

[3] Between 2000 and 2010, metro Atlanta’s Hispanic/Latino population grew from 268,851 to 547,400. Mike Carnathan, “ARC Regional Snapshot: Growth is Strong in Metro Atlanta’s Hispanic and Latino Communities,” Atlanta Regional Commission, February 2018, https://atlantaregional.org/news/workforce-economy/arc-regional-snapshot-growth-strong-metro-atlantas-hispanic-latino-communities/; Antonio Flores, “How the US Hispanic Population is Changing,” Pew Research Center, September 18, 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/18/how-the-u-s-hispanic-population-is-changing/.

[4] Mary Odem, “Global Lives, Local Struggles: Latin American Immigrants in Atlanta,” Southern Spaces, May 19, 2006, https://southernspaces.org/2006/global-lives-local-struggles-latin-american-immigrants-atlanta/; Mary Odem and Elaine Lacy, eds. Latino Immigrants and the Transformation of the U.S. South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009).

[5] Katia Hetter, “This is the world’s busiest airport,” CNN, September 16, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/worlds-busiest-airports-2018/index.html.

[6] “Atlanta in Focus: a Profile from Census 2000,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/research/atlanta-in-focus-a-profile-from-census-2000/; “The World in Atlanta: An Analysis of the Foreign-Born Population in Metro Atlanta,” Atlanta Regional Commission, March 2013, http://documents.atlantaregional.com/arcBoard/march2013/dr_regional_snapshot_3_2013_foreignborn.pdf; Marilyn Harter, Marilynn Johnson, et al, What’s New About the New Immigration? Traditions and Transformations in the United States since 1965 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[7] Susan Hardwick, “Toward a Suburban Immigrant Nation,” in Singer, Hardwick and Bretell, eds. Twenty-First Century Gateways; Mary Odem, “Unsettled in the Suburbs: Latino Immigration and Ethnic Diversity in Metro Atlanta,” in Singer, Hardwick and Bretell, eds. Twenty-First Century Gateways. During the 1990s, Atlanta’s suburbs grew by 44%, for example. “Atlanta in Focus: a Profile from Census 2000,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/research/atlanta-in-focus-a-profile-from-census-2000/; Paul McDaniel, Darlene Xiomara Rodriguez, and Anna Joo Kim, “Creating a Welcoming Metro Atlanta: A Regional Approach to Immigrant Integration,” Atlanta Studies, April 26, 2018, https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180426.

[8] Anna Joo Kim, “A Welcoming (and Sometimes Not) America: Immigrant Integration in the New South,” Metropolitics, November 1, 2016, https://www.metropolitiques.eu/A-Welcoming-and-Sometimes-Not.html.

[9] By 2013, the population on Buford Highway was composed of: 48.7 % Hispanic, 33.5 % White, 11.9 % African American, and 4.1 % Asian, according to a study conducted by DeKalb County. Buford Highway Corridor Study, DeKalb County, 2014, 6, http://web.dekalbcountyga.gov/planning/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Buford-Report-Final.pdf; Lauren Booker, “Havana Sandwich Shop, 43 years in business, “https://www.wabe.org/buford-highway/; Southern Foodways Alliance, “City Guide Atlanta: Buford Highway,” https://web.archive.org/web/20110716112907/http:/www.southernfoodways.com/images/Atlanta.pdf; David Landsel, “A Beginner’s Guide to Atlanta’s Buford Highway,” Food and Wine, April 22, 2019, https://www.foodandwine.com/travel/restaurants/buford-highway-atlanta-best-restaurants.

[10] Early refugee populations in Atlanta also included Mariel Cubans in the 1980s and Serbians/Bosnians in the 1990s. The detention of 2,500 Cubans in US Penitentiary in Atlanta led to a riot in November 1987 to protest conditions and deportations; Ronald Smothers, “Cubans End 11-Day Prison Siege In Atlanta, Freeing All Hostages,” New York Times, December 4, 1987, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1987/12/04/105387.html?pageNumber=1.

[11] “Refugees and Immigrants in Georgia: The Facts,” Coalition of Refugee Service Agencies, 2018, https://crsageorgia.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/fact-sheet-2018-1.pdf.

[12] Katy Long, “This small town in America’s Deep South welcomes 1,500 refugees a year,” The Guardian, May 24, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/may/24/clarkston-georgia-refugee-resettlement-program; Patrik Johnson, “Ellis Island of the South,” Christian Science Monitor, January 17, 2016, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2016/0117/Ellis-Island-of-the-South.

[13] Stephanie Stokes, “How Refugees Helped A Struggling Ga. Grocery Store Succeed,” WABE, January 26, 2016, https://www.wabe.org/how-refugees-helped-struggling-ga-grocery-store-succeed/ ; Warren St John, Outcasts United: An American Town, a Refugee Team, and One Woman’s Quest to Make a Difference (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2009).

[14] Arthur D. Murphy, Colleen Blanchard, and Jennifer A. Hill, eds. Latino Workers in the Contemporary South (Athens, University of Georgia Press, 2001); Terry Easton, “Geographies of Hope and Despair: Atlanta’s African American, Latino, and White Day Laborers,” Southern Spaces, December 21, 2007, https://southernspaces.org/2007/geographies-hope-and-despair-atlantas-african-american-latino-and-white-day-laborers/.

[15] Jeremy Redmon, “Immigration arrests target Somalis in Atlanta area,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, April 13, 2017, https://www.ajc.com/news/immigration-arrests-target-somalis-atlanta-area/uYatzrGTOkEGWuwocYmReJ/; Joel Rose, “How Metro Atlanta Became A ‘Pioneer’ Of Immigration Enforcement,” NPR Morning Edition, February 13, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/02/13/585301595/why-atlanta-embraces-trump-administrations-immigration-crackdown; “ICE, IRS search Hispanic grocery stores in Atlanta area,” ABC News, December 12, 2019, https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/ice-conducting-search-warrants-sites-atlanta-area-67692911; Elwyn Lopez, “Atlanta terminates relationship with ICE: What does it mean for the city?,” 11Alive, September 7, 2018, https://www.11alive.com/article/news/local/atlanta-terminates-relationship-with-ice-what-does-it-mean-for-the-city/85-591983534; Priscilla Alvarez, Geneva Sands and Maria Santana, “ICE set to begin immigration raids in 10 cities on Sunday,” CNN, June 21, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/21/politics/ice-immigration-raids/index.html.

[17] Mary Claire Kelly, “Atlanta History Center Retells City’s Story In ‘Gatheround,’” WABE, June 21, 2016, http://cp.wabe.org/post/atlanta-history-center-retells-city-s-story-gatheround.

[18] Nasim Fluker, “Community Partners: Neighborhood Initiative,” History Matters: Atlanta History Center (Summer 2019): 22 https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/assets/documents/AHC_History_Matters_Spring_2019_Final_Low_Res.pdf