Coffee Tables Books, Pulp Fiction Covers, and Courtroom Photography: Finding & Understanding the Art in Historical Interpretation

03 March 2021 – Doris Morgan Rueda

Art was how I first encountered and understood history. Today, as a doctoral candidate researching the transnational legal history of juvenile justice in the American borderlands, I explore the history of the surveillance and policing of youth in places such as public schools, places of worship, and social services through historical visual sources and my own multi-media art. This post explores the intersection of art and history and how merging these two disciplines enriches our understanding of the past.

Growing up, history and art were always synonymous to me. My immigrant mother hung Muisca tunjos (South American anthropomorphic figurines) on the walls and collected glossy colorful photo books of Colombia which gave her the opportunity to share Colombian history and culture to guests whose only other exposure to her heritage was derogatory jokes about Colombian drug dealers. Whenever a curious house guest inquired about her accent or background, my mother would deftly draw their attention to images of Andean landscapes, the metropolis of downtown Bogotá, or pre-Columbian Muisca art.

The coffee table books of my childhood that were always prominently displayed in the living room. For years, the only thing my mother would ask family to bring her were illustrated books, preferably in English, so that she could share them. Photo credit: Doris Morgan Rueda

I always thought about the art and history that surrounded me during childhood. But prior to 2020, I never recognized my art as anything more than an escape and a form of stress relief—something to do when I wasn’t reading, studying, or working. In graduate school, I gravitated to primary sources such as images, films, lurid newspaper descriptions that bordered on pulp fiction, photographs or drawings in city pamphlets addressing juvenile delinquency (especially the clothes, accessories, and makeup or hair styles associated with delinquency)—objects and creations that belong within the realm of visual culture as defined by John Walker and Sarah Chaplin in their book, Visual Culture (1997). While visual culture correctly pushes historians to take seriously the many forms art can take, from fine art to crafts to the art of spectacle, it is sometimes only applied to things that appear obviously visual and only ever used as a tool of analysis. Visual culture is something for historian to be study, rather than something to be involved in. This is where my approach differs.

As an artist who has experimented with various mediums and styles, I began to see art, and artistic decision, in more sources than just the traditional photographs or book art. I also saw it as having more possibilities than just a way to approach items in an archive. I took this ethos into my analysis as much as I did the language of those pamphlets or the police statistics in annual crime reports. Finding the art in these legal documents allowed me to tell a more interesting story about the way courts, but also people, used visual cues to send messages of power and resistance. It pushed me to become involved in making my own visual culture as a historian to both analyze and argue.

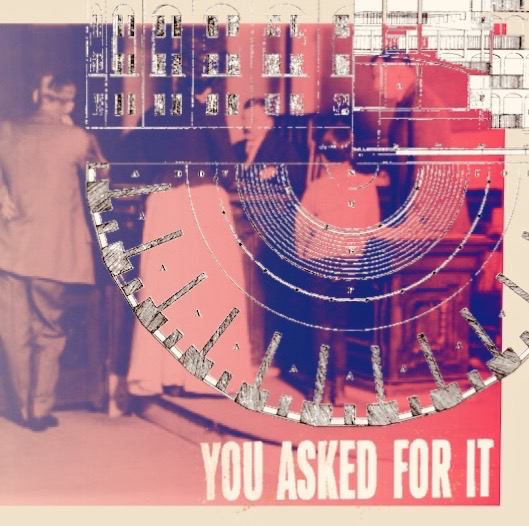

My work as an artist also began to change as my research progressed. As my research on the history of juvenile justice and the legal experiences of Latinx youth along the U.S.-Mexico border developed, my art took on my own heritage but also more serious subjects. The piece seen above in the image below (“All Eyes on You”), for example, was inspired by my research and my thinking about how juvenile justice system changed during the twentieth century. The original photograph in the background of my work is in the collection at Tate Britain. It is a 1910 photograph by American photographer Lewis W. Hine. Hine took the photo during his work with the National Child Labor Committee. The photograph captured my attention because it typified the power dynamics of early juvenile courts with a judge overseeing police, women probation officers, and the child at the center of the “locus of power,” something French sociologist Jacques Donzelot wrote about in The Policing of Families (1977). To foreground this locus of power, I utilized an illustration by Willey Reveley found within Jeremy Bentham’s book Panopticon; Or the Inspection House (1787), which introduced the world to his concept of a single-point, surveillance-driven prison, to draw attention to the court’s focus, the child. By overlaying the panopticon onto the court, with the child at the center, I hoped to re-situate our attention to the child’s experience of the court, an experience that is often told to us by the adult authority figures around the child and not the child themselves. To connect this piece to the present, I transformed it into a pop-art-inspired collage using a bright pink and purple color tone and a caption from a pulp fiction cover of Ian Fleming’s You Asked For It (1954).

All Eyes on You (2020). Mixed Media by Doris Morgan Rueda

My art uses contrast to tell stories about historical continuity and points to the historical roots of modern injustices, as well as utilizing humor and absurdism to explore human experiences. It was my training as a historian that gave me the tools to insert analysis and social criticism into my art, but my work as an artist trained my eye to approach historical analysis and legal history in a more creative and innovative way.

I see the role of art and visuals as necessary in historical interpretation. In my field of legal history, analysis prioritizes the written. But that misses the fact that many people also interact with the law visually. The symbols of the law, the courtroom, the judge’s robes, even the ritual of the legal process is understood visually rather than textually. This approach breathes a different life into a historical analysis of legal history. This is where I see the benefit of thinking visually, artistically, or even experimentally. The language of a juvenile court could be one of reform and parens patriae. But if the space is arranged to mirror an adult criminal court, what a child hears and what they feel or experience are two different things. Do they leave feeling that the court is only acting like a friend but treating them like an adult? What does this also reveal about the court’s perception of itself? In materials produced by the court or social services, what message is being composed in photographs or drawings? These questions were inspired less from my historical reading or any seminar class, but rather from my love of—and collecting of—pulp fiction covers and artistic representations of the law where audiences must rely on those tiny details to understand the narrative.

This merging of historian and artist, as both a set of identities and a set of methods, was formalized during my dissertation prospectus defense. I made the decision to create pieces inspired by my research and use them during my virtual prospectus in the midst of COVID-19, including the juvenile court-panopticon-inspired collage, as a way to demonstrate the many ways my historical inquiry takes form. Placing my art alongside my research proposal symbolized these two identities coming together in how I present myself as an academic. It is a practice I will continue in my dissertation with artwork accompanying each chapter and other future academic work. Interpreting history through art as well as through text are equally valid forms of scholarship and, in fact, they mirror each other. As historians we must select from many pieces of evidence to compile an argument in an article, book, or dissertation. We decide which primary source will be discussed with another primary source. We must make sense of how we will tell the story (thematically, chronologically, or geographically), as well as many more critical decisions that shape our final project. This curation of our interpretation and presentation is, in itself, an art.

Utilizing art as a historian pushed me to reconsider how I approach analysis as well as presentation. No longer limited to historical conferences, juried art shows are now venues for me to make historical arguments about legal history in a single piece of art to an entirely different public audience. I welcome more historians to explore their artistic side and embrace the experimental. Like the coffee table books that my mother used to educate visitors about her country’s history and culture, art gives historians a method of connecting the past and the present in a way that doesn’t rely on manuscripts or articles. The visual world opens history to everyone.

This is amazing!

Beautifully written. Love this creative visual history.

I loved this story, no one could described this culture better than you