Editor’s Corner: Burdens Borne, and Raised

18 November 2020 – James F. Brooks

Editor's Corner, The Public Historian, campus history, slavery, Indigenous People, historic preservation, TPH 42.4, archaeology, public history, deindustrialization

Editors’ note: We publish The Public Historian editor James F. Brooks’s introduction to the November 2020 issue of The Public Historian here. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members and to others with subscription access.

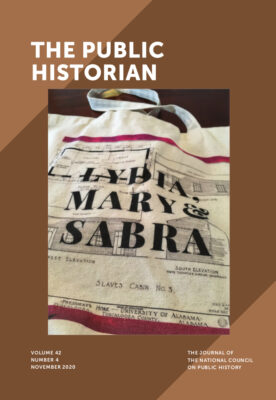

Cover of the November 2020 issue of “The Public Historian.” The cover photo depicts a tote bag printed with a 1933 Historic American Buildings Survey map and names of three enslaved women. Image credit: James F. Brooks.

I write this knowing that by the time we come to print, our 2020 presidential election will have taken place, and our work ahead, for better or worse, perhaps clarified. Many of us have endured these past four years in the cycling of the pendulum’s arc between despair of our present and hope for our future. With the amplitude of the arc, in energy and reach, as yet unclear, I trust our issue’s contents prove affirming of the latter.

We begin with a Roundtable that features deeply personal and powerful pieces from four Black women scholar-activists who have served in the vanguard of public historical engagement with the history of slavery in our nation’s colleges and universities. My arrival last summer at the University of Georgia coincided with the announcement of a unique competitive funding challenge, sponsored by an anonymous donor, of $100,000 in research funding for the study of the history of slavery at the university. Under UGA historian Chana Kai Lee’s leadership, twenty-two faculty from eight departments or programs submitted a winning proposal to engage in two-years’ archival and community research, which is underway. This grant also presented an opportunity for TPH to expand that place-based focus to one that forefronted the professional and emotional work that Black women historians have born in lifting human bondage, in our supposedly most enlightened institutions, toward the light of revelation and repair over the last two decades. These pieces by Professors Lee, Hilary Green (University of Alabama), Rhondda Thomas (Clemson University), and Leslie Harris (Northwestern University) are the result. When we read the drafts, managing editor Sarah Case and I found them so important to our field that we sought an additional voice, Tiya Miles of Harvard University, to lend her insights as a leading public historian in critical race and justice studies, to pen a contextualizing foreword. We’re grateful for each author’s personal courage in telling their stories, and hope they will sustain us in the work that lies ahead.

Our core articles begin with Andrea Burns’s engaging history of an abject failure: the “Autoworld” theme-park in Flint, Michigan, that—meant to revitalize a city on its heels—instead found its doors closed in a mere six months. In the course of her research, she found ties between Autoworld, the Flint water crisis, and the auto industry’s flight toward the suburbs.

Beneath the suburban hills of California, however, archaeologists Tsim Schneider, Khal Schneider, and Lee M. Panich find a different story. Indigenous peoples of the Franciscan Missions were neither the grateful neophytes of Christian imagination nor the abject subjects of a thinly disguised convict labor system. Across Alta California, Indigenous peoples exercised creative resistance to and resilience in the face of the Franciscan regime that allowed continuity in kinship, culture, and community. The physical landscape serves as an active force in these stories, reminding us that the oak-covered hills and valleys are more than scenery, but places where cultural knowledge is conserved.

Ross J. Wilson brings us to realize the potential for dinosaur museums to serve as important agents for illuminating the place of paleontology, climate science, and history to the visiting public. As visitors come to see humanity’s brief presence in the sweep of geologic and climatological transformations, and the vulnerability of all life species to forces vastly beyond human control, interpretation can forefront humility and empathy in the stories of vanished species, and a sense of urgency that we in the apex of the Anthropocene to think about how alterations in our present may alter our future on the planet.

We conclude this issue with Lydia Mattice Brandt’s “Report from the Field” on her work to awaken professional and public audiences to the historical value of Modern (1945–75) architecture. Benefiting from the public’s revitalized enthusiasm for Midcentury Modern design—reflected in any West Elm catalogue—she argues that we have an opportunity to talk about the fetishism of “age” and enliven conversations across generations, in which the older generation reexamines designs they once considered quotidian and the younger generation to populate “places” with “people.” Kindling such enthusiasm in the public, she argues, is the first step toward preserving the “Modern” past.

~James F. Brooks is editor of The Public Historian, the Gable Distinguished Chair of History, University of Georgia, and Research Professor in History and Anthropology, UC Santa Barbara.