Editor’s Corner: History, Memory, and Marketplace

10 March 2021 – James F. Brooks and Sarah H. Case

Editors’ Note: We publish The Public Historian editors’ introduction to the February 2021 issue of The Public Historian here. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members and to others with subscription access.

In December, 2016, Sarah H. Case and I met for our monthly editorial meeting, little expecting that this special issue of The Public Historian would be one consequence. Sarah had, the day before, returned from Los Angeles, where she’d taken her two daughters and niece to the American Girl Place in The Grove, downtown Los Angeles. As she explained, a visit to the store is more than just an opportunity to buy a doll; rather, it is itself an experience that can last an afternoon. On two floors, the store offers a wide array of dolls and doll accessories—most unconnected to the brand’s historically-themed merchandise. There is also a salon, where doll owners must make an appointment, sometimes several hours in advance, for their dolls to have their hair styled, their nails painted, or receive a facial. Hungry visitors (who have reserved in advance) can visit the second-floor café. Food is mostly kid-friendly and prix fixe, so that at their lunch Sarah’s sister’s salmon and her younger daughter’s pasta with butter both ran $25. Both, however, came with starters and desserts, soft drinks, and service that is sweet towards the girls and a bit cheeky to adults (“Ladies, will we be adding a prosecco this afternoon?”). Dolls are given booster seats and tiny plastic cups and plates. Leaving the café, feeling overwhelmed by the sugar, the signature pink branding, and sheer amount of doll-sized stuff (and perhaps wishing that she had agreed to that prosecco), Sarah found herself among the alcoves to each of the historically themed dolls. Here, small rooms dedicated to a specific character offer dolls, books, and meticulously created furniture, clothing, and accessories that tell their stories. Staring at Josefina’s 1824 Christmas outfit, Samantha’s 1904 bicycle, and Julie’s 1974 flower-power bed, she wondered: could these, along with the books accompanying each character, offer a meaningful affective connection to the past for girl consumers?

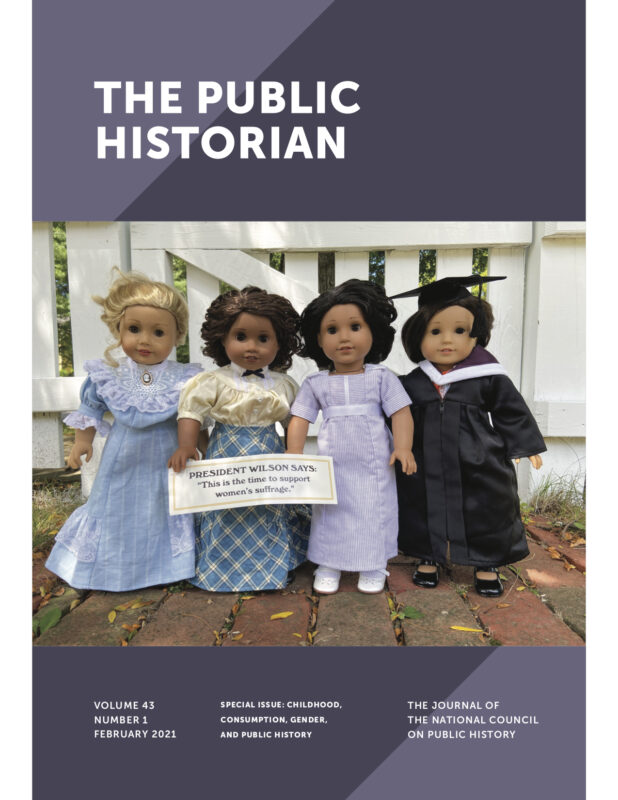

Cover of the February 2021 special issue of “The Public Historian.” Cover photo credit: Rebekkah Rubin.

Those who know Sarah’s central role in maintaining the scholarly rigor and timeliness of our journal might, as I did, arch an eyebrow at this news. I soon, however, found my eyes wider open to an historical “gateway” that launched us toward this issue. Our question, as public historians, involved a wish to better understand how American Girl dolls came to “life” as historically situated characters, and how their lives, in the play of their owners, spurred historical curiosity and knowledge acquisition. Although the dolls and their extensive accessories seemed frivolous (and are certainly expensive), the books associated with the historical dolls provided Sarah’s then-seven-year-old daughter with stories that she found compelling about girls during during the War of 1812, New Mexico in the 1820s, and the Lower East Side of New York City in the 1910s. Further, we both began to notice that many thirty-something professional historians—especially those engaged in publicly facing work—cited American Girl as an inspiration for their careers. We have to thank Leah Glaser of Central Connecticut State University for suggesting the idea of examining American Girl in the pages of TPH several years ago. Our colleague Lisa Jacobson, a specialist in the histories of consumption, family and childhood, business, and gender, saw a promising opportunity to craft a collection of essays around childhood, commerce, and consumption. With encouragement from NCPH president-elect Marla Miller, we shaped a call for proposals on the theme Childhood, Commerce, and Consumption. This is the result.

The nine essays in this issue represent diverse ways of pondering the intersections of consumption and historical understanding. Several, not surprisingly, engage directly with American Girl. Emilie Zaslow offers an overview of how the company shifted its presentation of the American past over time, identifying four periods that represent distinct interpretative approaches. Allison Horrocks and Mary Mahoney offer a “Report from the Field” about their work on their popular American Girls podcast, in which they employ listeners’ affection for the dolls and books as a starting point for delving into lighthearted yet sophisticated historical analysis. We are fortunate to include another “Report from the Field” by Mark Speltz, former historian with American Girl, who gives a fascinating behind-the-scenes view of the process of creating Melody, a civil rights-era character. These contributions directly speak to our original curiosity about American Girl’s presentation of history to young girls—its successes, as well as its limitations.

Molly Rosner’s essay on the book One Crazy Summer, on the other hand, examines a story about the recent past that presents the kind of young girl largely absent in the American Girl series. Set in Oakland, California, in 1968, the book engages head-on with issues of racism, family abandonment, and radical politics. Most strikingly, the book frankly depicts its protagonist as capable of anger and unpleasantness—qualities usually missing in portrayals of girls in literature marketed to children. Another “Report from the Field,” by Kathleen Franz and other curators of the National Museum of American History, also engages directly with efforts to honestly depict girls’ anger. In designing the new exhibition Girlhood: It’s Complicated, curators used the inspiration of zines of the 1990s to foreground cultural expressions of young women’s creative agency. The exhibition examined the lives of American girls over the last two centuries, and sought to complicate stereotypes of girlhood by analyzing race and class in its interpretation of girls’ work, education, health, and fashion. Also centering girls as creators is Jennifer Helgren’s analysis of historical research conducted by Girl Scouts and Camp Fire Girls as part of the Bicentennial celebrations of the mid-1970s. Helgren finds that young girls, inspired by contemporary interest in social history and feminism, conducted oral histories and engaged in research to identify “hidden heroines” in their communities.

Not all of the contributions focus on girls. Colin Fanning’s examination of LEGO reveals the Eurocentric and gendered aspects of a product marketed as a universal “good toy.” To assess how the video game Civilization might enliven historical thinking, John Majewski analyzes the social media posts of fans, mostly teen boys and young men. In a close read of the 1970s TV cartoon series Schoolhouse Rock! Paul Ringel notes that the popular show was more successful in teaching grammar and math than historical complexity, but believes its model of reaching children through its combination humor, catchy visuals, and great music could be successfully updated with greater attention to nuance and diversity for twenty-first-century audiences.

Together, the issue inspires us to attend to how play, performance, and practice are interwoven as children learn about history from consumer products, in complex if sometimes contradictory ways. We hope our authors’ insights prove useful to public historians in archives, classrooms, and at the “front of the house.”

Finally, this issue marks James’s last Editor’s Corner. I now am honored to pass the editorship to Sarah, who after eight years as The Public Historian’s Managing Editor, has been selected by UCSB and the NCPH to assume a new title, that of Executive Editor. Joining our editorial board in supporting Sarah are Harvee White, Education Manager of the Augusta, Georgia, Museum of History, and Dr. Jennifer Dickey, Coordinator of the Public History Program at Kennesaw State University. I am delighted to see Sarah’s professionalism and deep knowledge of the field so recognized, and look forward to the years ahead in my continuing duties as Senior Consulting Editor.

~James F. Brooks was editor of The Public Historian and is the Gable Distinguished Chair of History, University of Georgia, and Research Professor in History and Anthropology, UC Santa Barbara.

~Sarah H. Case, editor of The Public Historian, earned her MA and Ph.D. in history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she is a continuing lecturer in history, teaching courses in public history, women’s history, and history of the South. She is the author of Leaders of Their Race: Educating Black and White Women in the New South (Illinois, 2017) and articles on women and education, reform, and commemoration.