Expanding Historic Narratives to Mobilize Around Our Climate Emergency

11 January 2022 – Donna Graves

Editor’s note: Today we share our next installment for the “Our Climate Emergency” series. Donna Graves, one of the editors of this series, investigates her role as a public historian and explores the visual nature of the climate crisis.

A whiteboard posted at Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Park stated “During WWII, the United States mobilized around a common cause” and asked visitors “What cause should this country mobilize around next?”

“This is what humans do—we turn the world into a story and put ourselves at the center of the plot.”

~Ben Ehrenreich, Desert Notebooks: A Road Map for the End of Time

“Stories are compass and architecture, we navigate by them, we build our sanctuaries and our prisons of them.”

~Rebecca Solnit, The Faraway Nearby

October 2017—the first time that wildfires transformed my Bay Area home into a regional dystopia—was the moment that forced me to face the question of what I could do about climate change. The more frequent and devastating wildfires, heat waves, and floods that many of us feared were in the future were, in fact, already happening. Watching my carbon footprint, showing up at protests, and donating to climate organizations no longer seemed an adequate response. I began to strategize about how my skills as a public historian could be relevant to this issue. I’ve always seen my work, which has focused on creating a more inclusive record of U.S. history in the public realm, as a form of social justice practice. What would applying these skills to climate change look like?

Because my projects have focused on particular places, I started to pay closer attention to what colleagues in the field of historic preservation were saying and doing about climate change. I found a prevailing focus on two topics: 1) managing climate change threats and impacts to historic buildings and archaeological sites and, less frequently, 2) discovering lessons from these structures and remains about sustainable ways to build, and live, in specific locations. The emphasis was on quantitative scientific data and the material aspects of historic site, with far less attention to how the intangible, historic meaning of places might be leveraged in our fight against climate change.

Centering climate science in how we interpret the current crisis is critical. Nevertheless, it misses powerful opportunities to connect cultural resources and climate change information in more places and in more ways that are engaging, meaningful, and relevant to visitors and community members. A focus on human narratives allows people to see themselves and their communities in the story. It also accounts for the environmental injustices exacerbating the impacts of climate change for marginalized communities. Placing humans at the narrative center can make interpretation more relevant and can spotlight how people can come together in creative and resilient ways to address the changing climate. Weaving human resilience into a climate change narrative from the start allows interpretive choices that can lead to discussions with visitors about the transition to climate solutions in ways that can be seamless and inspirational.

Public historians add important expertise to this endeavor by working with communities to uncover local stories that help them better understand how they have arrived at this climate crisis and to find inspiration in past events that offer models for handling enormous change. Public historians can help scientists, archaeologists, journalists, community activists, and others find effective ways to convey the scale and urgency of the challenge posed by climate disruption.

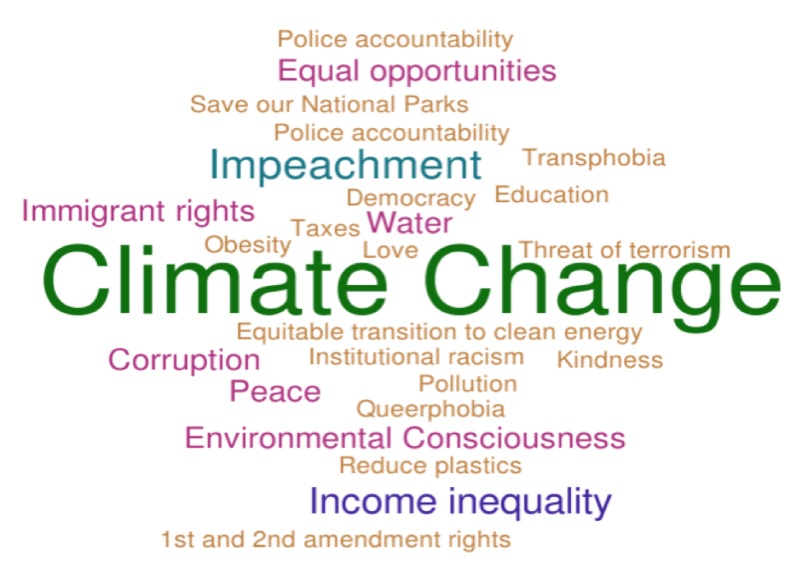

Post-it notes responses were gathered and organized in monthly words clouds by staff. August 2019’s, like all of them, showed that climate change was the cause most often cited.

Photo credits: Elizabeth Villano

As I contemplated what public history practice could offer to movements mobilizing to combat climate disruption, I began with Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park, a site I helped to establish in Richmond, CA and which I have been working with for more than twenty years. I collaborated with NPS guide Elizabeth Villano to develop a ranger talk titled “When History Rhymes: Lessons from the Home Front” that drew from Richmond’s history to engage visitors in conversation. Rather than explicitly starting with climate change, the talk used Audience Centered Experiences techniques to encourage visitors to analyze WWII posters calling for “total mobilization” to consider what issues might rally them to make changes in their lives today and to imagine how we might collectively prepare for unprecedented changes ahead of us. Most visitors intuitively connected the program about past mobilization to the mass transitions our nation will need to make to combat climate change.

Despite the many barriers raised by the pandemic, Villano and I continued to partner in 2020 to develop a narrative framework that is transferable to interpreting many places—whether they are sites valued primarily for their associations with “nature” or “culture”—and can support interpreters and educators who use cultural and natural history to discuss climate change in ways that stress relevance and motivate the public. The themes we’ve explored in this work-in-progress contribute to bringing climate justice into the conversation by helping visitors understand that factors exacerbating the impacts of climate change on certain populations that have historic roots in social inequities created by capitalism, colonialism, racism, sexism, and more. For example, at the Rosie the Riveter site interpretation of climate change aligns with the park’s emphasis on social history. Questions that could support interpretation at the park include, “How do climate change effects fall unequally on residents according to income, wealth, race, gender, disability, etc.?” Considering that Richmond is a city with health challenges caused by heavy industries, how will additional health effects brought on by climate change impact residents? Richmond’s relatively affordable housing costs makes it a magnet for lower-income workers. Will this factor draw new residents due to the projected increase in climate migration in the coming years? Questions like these can amplify the longer narrative arc at the Rosie the Riveter site while reframing visitors’ understandings of the impacts of climate change.

“History and Hope: Interpreting the Roots of Our Climate Emergency and Inspiring Action”

The National Park Service’s Cultural Resource Office and Climate Change Response Program are currently supporting a project to develop a toolkit based on this more human-centered and narrative approach. Villano and I are working with Nichole McHenry, NPS Diversity and Inclusion Program Manager, to test and expand our preliminary ideas with a small range of parks and then, by early 2022, present a tool for supporting national parks and other sites with expanded strategies for interpreting climate change and inspiring action.

We believe that climate change interpretation is an important next step in the role of historic places as both reflections of—and shapers of—societal values, and as inspirations to action. As heritage pioneer Tilden Freeman wrote in 1957, “the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.” The narratives we craft can reveal histories of loss and resilience, deepen understanding of and connections to places that will undergo dramatic changes, and reinforce the importance of understanding legacies of environmental injustice in addressing the effects of our climate emergency. In addition to making the historic roots of climate change clear, we can provide examples when society reorganized to face immense challenges. Narratives like these can allow visitors and community members to envision their own roles in addressing our climate emergency with the knowledge, urgency, and hope required.

~Donna Graves is an independent public historian/urban planner based in Berkeley, CA. She develops interdisciplinary projects emphasizing social justice and sense of place—and now the importance of mobilizing around the climate emergency. Her recent essays have appeared in The Public Historian, Change Over Time, and Columbia University’s Issues in Preservation Policy series.