Farm Road: Rural gentrification and the erasure of history

13 July 2016 – David Rotenstein

Farm Road, May 2016. Photo credit: David Rotenstein.

In its infancy, gentrification was a word used to describe changes in urban neighborhoods. Now, gentrification has been documented in suburbs and rural areas around the world. It is even sweeping through Washington, DC’s suburban counties, where farmlands are being converted into housing and mixed-use developments. The “Farm Road” case in Maryland’s Montgomery County is a troubling example of rural gentrification and historical erasure.

Montgomery County is an affluent Washington suburb with about a million residents. Its southern portion reflects proximity to the District of Columbia: densely developed residential suburbs and commercial sprawl. The upcounty area includes a substantial agricultural reserve and many large former farms ripe for development as demands for housing increase. This demand has created a substantial gap in the low value of the property as agricultural versus a potential greater value if it were to be developed. This “rent gap” is the economic engine underlying gentrification.

Dellabrooke subdivision. Photo credit: David Rotenstein.

The Farm Road case involves a historically African American community created by freed slaves who bought land and cultivated farms near Sandy Spring, about 30 miles north of the U.S. Capitol. In the early 1990s a developer began subdividing properties between two county roads, Brooke Road on the south and Gold Mine Road on the north. Cutting through the eastern portion of these tracts was a roadway connecting the African American farms. The developer then constructed large new homes in the lots in a residential subdivision called “Dellabrooke.”

The developer’s plats failed to show the rough right-of-way that had been illustrated in real estate atlases and topographical maps published since the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Deeds recorded in county land records contain plats that show the road and the “Farm Road” name is memorialized in the metes and bounds describing the tracts where it forms a boundary.

Rural Gentrification and Erasure

Since the word “gentrification” was coined in the early 1960s it has taken on meanings beyond what British geographer Ruth Glass originally intended: the replacement of working-class housing and people by more expensive housing and middle-class newcomers. Today, there’s “commercial gentrification,” “student gentrification,” “industrial gentrification,” and many others. Each denotes the conversion of space and the displacement of people in response to local economic conditions and facilitated by public policies like zoning.

Rural gentrification involves the transformation of former agricultural areas and other greenfields into new developments and the “subsequent displacement of working-class rural residents as a result of rising local land and housing process,” wrote geographer Eliza Darling in 2005. Local government’s changing zoning laws and land use classifications to encourage development and the production of new housing oftentimes facilitate it.

Erasure is a metaphor historians and anthropologists use to describe the replacement of one historical narrative by another. Like gentrification, erasure involves displacement. It is a complicated process that combines “forgetting” with historical revisionism to privilege a particular group promoting the new narrative. There are few cases where the act of erasing is visible and is a key part of the erasure or displacement. Farm Road is one.

The Farm Road, Contesting Erasure

“Farm Road” isn’t an official name for the narrow rutted route; rather, it’s a vernacular place name that evolved from local usage and it was a way for surveyors to label a landscape feature in maps. The 10-foot-wide road was an artifact that developed over more than a century of agricultural land use. In legal terms, it was an easement: property belonging to a third party that others have a right to use.

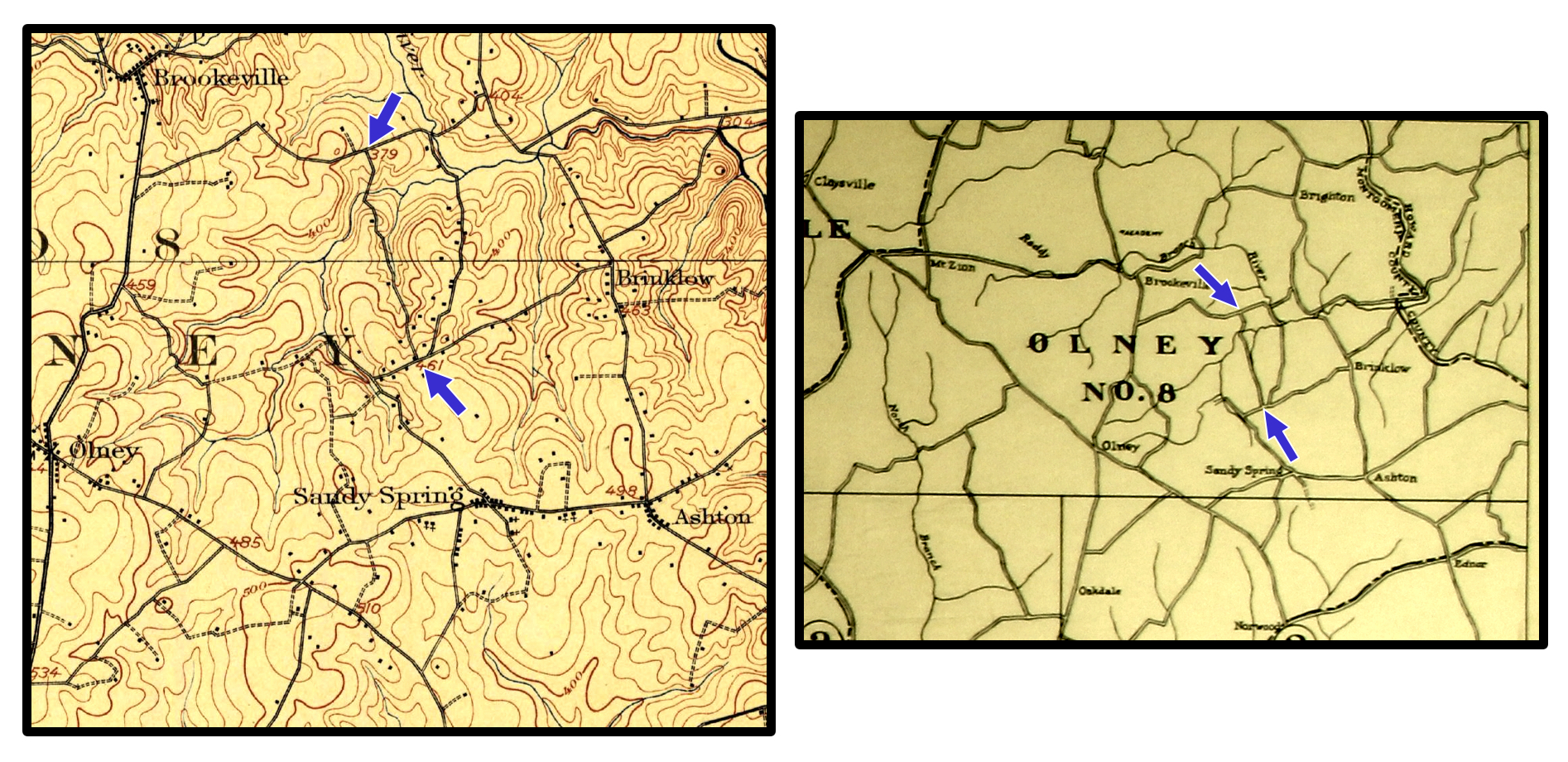

Historic maps illustrating the Farm Road corridor (blue arrows mark termini). The map on the left is from the 1908 USGS Rockville, Maryland quadrangle and the map on the right is from the “1916 Real Estate Atlas of the Part of Montgomery County Adjacent to the District of Columbia.” Image credit: Public domain.

Because “Farm Road” had never been a dedicated public right-of-way and no legal easement instruments had ever been filed, Farm Road didn’t legally “exist.” When residents of the new Dellabrooke subdivision blocked access to Farm Road by placing a chain across the road, longtime residents in the parcels lining Farm Road filed complaints with county agencies.

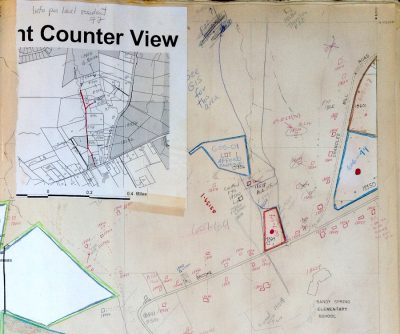

Maryland-National Capital Planning Commission “Address Book.” Addresses crossed out in the right portion of the map are along the “Farm Road.” Photo credit: David Rotenstein

When residents and local activists reviewed the Montgomery County Planning Department’s master “address book”–large bound survey plats where street addresses are recorded–they found that the addresses denoting their properties had been crossed out with red Xs. According to county officials, not only didn’t the Farm Road exist, but neither did the residents’ addresses since they didn’t front on a legal road. This meant that property sales, future subdivisions, and other transactions would be complicated because in the eyes of county regulators, the properties didn’t exist.

Finding no relief from Montgomery County officials, residents then began what has become nearly two decades of litigation. They filed lawsuits in federal and Maryland state courts “seeking millions of dollars and alleging fraud, deceit, conspiracy, race-based discrimination and violation of their right to due process,” a local newspaper reported in 2008.

The Farm Road case exposed systemic procedural problems in the county’s planning department. New rules were created for reviewing and approving new subdivision plats. The case was one of several that emerged between 2001 and 2010 in which planners had approved development plans that did not appear to conform to state and county law. Investigations were undertaken and the fallout included the resignation of the planning board chairman and an agency restructuring.

As Montgomery County was addressing the fallout from deficiencies in its planning department, Farm Road residents were litigating their case in the courts. The federal case was dismissed because the court found that the complainants had failed to “exhaust state remedies.”

After being rebuffed in federal court, the residents brought their case to the Circuit Court for Montgomery County. A county judge dismissed the case in 2011 and they appealed to the Maryland Court of Special Appeals, and finally to Maryland’s highest court, the Maryland Court of Appeals [PDF]. According to the complaint reviewed by the courts, “Petitioners in this case allege that [county officials] were involved with [the developers] in a scheme to erase Farm Road.” The state’s highest court ruled in January 2015 that the Farm Road residents’ complaint would not survive a motion to dismiss by the defendants and the case was closed.

The Farm Road case offers historians a unique window into the intersection of gentrification and the production and erasure of history. Over the past century, much of rural Montgomery County has been transformed into middle-class and elite suburbs for the nation’s capital. The process of producing space for progressively more affluent users has changed the county’s physical landscape, displaced residents, and, as far as Farm Road is concerned, resulted in the violent erasure of a cultural landscape and its traditional use.

~ David Rotenstein is a consulting historian based in Silver Spring, Maryland. He researches and writes on historic preservation, industrial history, and gentrification.

Yes, the Clarksburg debacle you reference demonstrated just how skewed Montgomery County planning had/has become with respect to developers. I had not heard of this case, so many thanks for sharing. I am sure there must be other pockets of African American communities–along River Road, up in the Poolesville area??–that may serve as comparisons? From Joan–a fellow MoCo resident

Erasure also happens when a rural area gets “discovered”.

In Western Wisconsin, where I live, we’ve been inundated by a wave of upper middle class people moving in (primarily due to a private Waldorf School). The housing prices have tripled and many who grew up there can no longer afford housing.

The new people primarily live on capital gains wealth, so they’re not producing new jobs or opportunities. They’re just taking advantage of the fallout of the Dairy Farm Crisis.

It’s rather tragic. My family has lived in the are for 170 years and I feel that the area’s history has been erased.

Thanks for putting a term forth that encapsulates what is happening.

Joan, and others,

If the county ever actively maintains a road, then it can be considered a ” prescriptive easement” which is openly used by the public. In fact, many rural roads operate to this day as prescriptive rights of way, with farms each owning to the center line. In this case, apparently local folks maintained the path and used it without it ever technically becoming public. If some residents only access is via a private roadway, then usually a private easement is created so it’s interesting that no one ever sought to secure a written easement, but we all know how things worked and how the local people may have simply been disregarded with respect to the roads they used to get to the bigger thoroughfares. I know of other examples where dirt roads were never paved and therefore reverted to the farms they crossed. The legal principals respect the private property owners and were obviously used on Farm Road to disregard any quasi public use of the roadway