Fragile history in a gentrifying neighborhood

20 March 2015 – David Rotenstein

race, preservation, advocacy, art, social justice, community history, memory, sense of place, gentrification, economic development

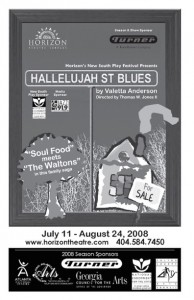

Over the past few years, I have been writing about gentrification and how it intersects with history in an Atlanta, Georgia, suburb. Twenty-five months and more than 50 interviews after I started talking with people and documenting neighborhood change in the Oakhurst area of Decatur, I met playwright Valetta Anderson, who works at Atlanta’s Woodruff Arts Center. In 2008, Anderson’s play about gentrification in her neighborhood, Hallelujah Street Blues, had been performed during the 2008 National Black Arts Festival. A Chicago native, Anderson had lived in Oakhurst for 18 years and was a participant in one of Decatur’s first public gentrification battles when she and a handful of neighbors sued the city in 2003 over a proposed property rezoning and townhouse development. The experience became Hallelujah Street Blues, a unique critical commentary on Decatur from an African American writer.

Yet no one had mentioned the play in any of the conversations I had with neighborhood residents. Nor did it appear in the neighborhood’s listserv; the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association’s monthly newsletter The Leaflet; or the Decatur Focus, a bimonthly magazine published by the city. The play had actually been staged in Decatur before its debut at Atlanta’s Horizon Theatre, and it received some press attention during its downtown production, including a profile of Anderson in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and a review in Creative Loafing, Atlanta’s long-lived alt-weekly paper. But it seemed strangely invisible–or at least submerged–in Decatur community memory. Its seeming erasure has led me to new questions about storytelling as a window on the recent past and a barometer for community values.

When I interviewed Valetta Anderson in January 2014, I asked her how she came to write the play. “Well, it was after we lost [the lawsuit] and everything was still fresh and I was angry and wanted to show the world,” she explained. “See, I’m one of those writers who thinks you can change the world by writing words down and people will hear it.”

Anderson’s script could have come from many of the interviews I had done with Oakhurst’s African American homeowners. The play validated the accounts I had collected, and it provided me with a road map to the legal case that inspired Anderson to write it. Hallelujah Street Blues captures the discord among family members in an African American household caused by displacement pressures . The question splitting the household was whether to sell the family home or to stay. “The local land grab brings family issues out into the open,” wrote Creative Loafing’s Curt Holman.

A small backyard orchard is one of the play’s settings. It’s where the family’s grandfather had planted some crabapple trees. A developer with rights to part of the backyard has plans to remove them. The orchard is family space, and the trees are a significant place with deep attachment ties among the family:

Your granddad planted these trees.

Your Uncle Nathan helped him put each one in the ground, same as you’re helping me.

You should’ve seen the two of them out here looking like two pods from the same tree.

Only difference was their size and the sound of their voices.

Anderson described the orchard’s significance during our 2014 interview. She didn’t use terms like “place attachment,” but her explanation sublimely captures the intangible losses displaced people experience. “This play, that guy just because his father had planted those trees and when I heard that, I heard him. And I realized even though that was not something I knew of, in particular, that happened I knew that people were leaving gardens. People were leaving doorjambs that had their kids’ heights carved into the wood.”

I later asked Anderson why no one mentioned the play to me, and she replied that it likely was due to how the play was marketed locally. Marketing may be one factor, but I think it is situated in a community context that privileges white history and the preservation of a municipal image over the story of racial and class division that Anderson’s play tells.

Hallelujah Street Blues doesn’t fit Decatur’s public image as a progressive and diverse community. John Keys, a former Decatur Historic Preservation Commission member, outlined for me how the city carefully crafts its municipal image to protect that image. According to Keys, manipulating history is part of that process: “They don’t really care about the gentrification of this community, obliteration of its history, or in getting involved in anything that smacks of ‘conflict’–which means they don’t want to take on ‘controversial issues’,” he wrote to me in July 2013.

I asked Keys about this in an interview the following year. “I don’t hear a whole lot of discussion about that and you know, at the Decatur Arts Festival and the Book Festival and the beer festival and the wine festival, there’s not a whole lot of opportunity to talk about those things,” Keys said as we discussed African American history in Decatur and the lack of preservation of black history sites. “And there’s certainly not at the city commission meetings. They don’t encourage that sort of thing.”

Valetta Anderson is equally forthright about the dynamics of race in Decatur. “This is not our town,” she said during our interview. “Decatur’s not our town. I mean we may have built Decatur, you know, put the bricks and mortar up and all but it’s not ours.”

A Decatur home being demolished in 2012. The house, which had been bought by a developer, had closets full of clothes and a full attic of belongings from the family that last lived there. Photo credit: David Rotenstein

As a historian, I can shoot pictures showing developers demolishing small homes with clothes still hanging in closets or a family’s entire history–papers, furniture, china, and baskets–being pulled from an attic by a backhoe claw and sent to a dumpster. I can use my interviews to, as ethnographer Clifford Geertz once wrote, turn dynamic events into static accounts. Hallelujah Street Blues and my conversation with Valetta Anderson gave me a different view. The play and Anderson’s memories are invaluable autoethnographic data, as well as showing how art can serve as both an emotional outlet and a way to preserve an important story not being reported elsewhere. And its near-erasure from community memory adds another layer to this complex story. It speaks to the stakes involved in documenting unwelcome perspectives–one of the larger historical issues emerging in my research.

~ David S. Rotenstein (Historian for Hire) is an independent consultant working in Washington, DC, and beyond.

Thank you, David, for adding “Hallelujah Street Blues” to your historical record. After all of the recent deaths of young African-American males, government grants of zoning variances to push Senior African-Americans from their bought-and-paid-for homes may seem minor. But it stokes the engines of deception, disdain, disregard, and disenfranchisement of ANYONE on fixed, middle class and lower incomes. Overreacting and deadly “law” enforcement is as color blind as gentrification. Watch your back, America’s Oakhursts. Karma’s a witch on a broom.

Thank you again, David, for adding your voice to this wilderness. I will, of course, share this article with all my friends onshore.

I have had the privilege of reading Valetta Anderson’s amazing Hallelujah Street Blues. I wish I had had the privilege of seeing it performed. It is a powerful literary work which stays with you long after you have finished reading it.

Thank you for this outstanding article highlighting Valetta’s own personal history surrounding Hallelujah Street Blues and the incredible gift of her talent she shares with all of us.

I saw Hallelujah Street Blues at Horizon, and it was a great play. It was so important because so much history is destroyed when gentrification happens. This play gave voice to a voiceless class of poor people. I hope they revitalize Valetta’s play again. It is an important piece of Atlanta’s history.

The gent in our lives happens to live in a gentrified neighborhood. I irony upon irony. I feel I violated and powerless too. A Chekovian joke.

I have labored many years with my cherry orchard and yes crabapple trees and family at the gent’s home. My identity is demolished by carelessness and poverty of respect. I would like to read this play.

I would like to explore wth the playwright about gentrification of a women life and how The macro reflects the micro resonating with the topic of urban gentrification. My son is an urban planner and we have discussed all points of view. She

knows how to reach me in Cincinnati.

The Cincinnati gent will never bother to read your play since it isn’t about jazz but I am always open and interested in a writer’s voice.

Ms V is complicit in my mental breakdown with my cheating husband Ron J Enyeart from Newport, Ky. He established you in our family’s gentrified house so he would not have to drive hours to Atlanta when his business dealings failed. How many years did he lie to me? You know. I called you to plea to you to leave my family alone. You scoffed. Since then, in Cincinnati, you “throw shade” in a disrespect;ful, bullying way when I approached you in peace. Ask yourself way you are defensive. Lynn from Cincinnati.