Raising the curtain: From extreme exhibits to artists in residence

24 July 2014 – Allison Weiss

Editor’s Note: In “What I’ve Learned Along the Way: A Public Historian’s Intellectual Odyssey,” outgoing NCPH President Bob Weyeneth issued a call to action to public historians to include the public more fully in our work by “pulling back the curtain” on our interpretive process—how we choose the stories we tell. In this series of posts, we’ve invited several public historians to reflect on projects that do exactly that, assessing their successes and examining the challenges we face when we let the public in through the door usually reserved for staff.

“Quakers and the Challenge of Freedom,” mixed media by Curtis Woody, 2014, was inspired by the collections at the Sandy Spring Museum, MD. Photo credit: Curtis Woody

If it’s true that museums only exhibit 2% of their collection, opening rarely or unused collections to people other than curators is one way for a museum to pull back the veil on the interpretive process to draw them “into an explanation of why some subjects are discussed at the site, but not others.”[1] The Sandy Spring Museum, a community history museum in Sandy Spring, Maryland, has always had an extremely small staff and has never employed a curator, making much of our collection off-limits. We are experimenting with ways to make it more accessible by allowing people without museum training the opportunity to work with our collection. Two projects, an Extreme Exhibit Makeover and an invitation to local artists to make work inspired by our collections, are attempts to connect community members more meaningfully with the museum, give them hands-on experiences that show how curatorial choices shape the interpretation of history, and bring new perspectives to our collections. Hopefully, along the way, the participants, staff, and visitors had some fun, too.

Extreme Makeover-Exhibit Style

The Extreme Exhibit Makeover brought together a dozen individuals who had never worked together before and had no affiliation with the Sandy Spring Museum to improve our permanent exhibits. Participants were selected through an application process and put on one of two teams, depending upon their experience. In the end, each team had a designer, a researcher, an artist, an educator, and other assorted museum professionals.

The goals of the project were: (1) to update exhibits on a shoestring budget of $1,200; (2) to have museum professionals look at the exhibits with fresh eyes and give them ample leeway to implement a new approach to interpreting Sandy Spring history; and, (3) to inject some humor into interpreting history.

The teams were shown the permanent exhibits, which were vignettes of a generic “old town” – the general store, the open hearth kitchen, the parlor, the one-room school, and so on – and were asked to select a section to makeover. One team chose the general store and the other team opted to dismantle three vignettes and start from scratch. While allowing this second option required a leap of faith in the abilities of the team members, museum staff approved general concepts, graphics, exhibit design, and text and object selection before anything was finalized. A temporary collections manager provided the teams with access to the artifact and archival collections and answered research questions.

The General Store team took a weak exhibit of an “any town” general store and focused on the concept of gathering place. They explored ways in which residents historically came together for social purposes and to better the community and then incorporated stories from the local fire department, places of worship, and the Sandy Spring social clubs, which date back to the mid-1800s.

The second team looked at how generations of soldiers reintegrated into society in their exhibit From Soldier to Civilian. The exhibit recreated a modern-day barracks with an original video of one soldier telling her personal experience in Afghanistan. Drawing from contemporary sources, like oral histories that they recorded with vets identified through the local military “readiness center” and historic sources from the museum’s archives, the exhibit tells a compelling story that shows the many similarities in the experiences of soldier/civilians from the Civil War to the current war in Afghanistan.

The Extreme Exhibit Makeover was more about process than product. The title, of course, was selected to make the project accessible. It was crowd-funded with more than fifty people contributing between $5 and $1,000. We created a blog in order to keep people up-to-date with what the teams were encountering and what decisions were being made. And the public was invited to watch the building and installation of the new exhibits, which took place over two weekend days during regular public hours. This also gave visitors the opportunity to ask team members questions about the project and the exhibits. The new exhibits have inspired staff to discuss the creation of programming that otherwise would not have been considered, such as programs specifically targeted at veterans.

If a visitor wanders into the exhibit hall at the Sandy Spring Museum today, s/he will encounter explanatory text as to how the exhibits were developed with this “extreme” process. But without that text there is nothing to distinguish these exhibits from exhibits at other small history museums. Was the project successful? Yes. We achieved the goals we set out to accomplish. We calculated that more than $50,000 was donated to the museum through materials and labor, and we received much publicity, including an article in the Washington Post.

Collections as Inspiration

The second way in which we are experimenting with collections access is through collaborations with artists. Again with the help of a temporary collections manager, we have thrown open the doors to the collection and asked, “What inspires you?” We offer this opportunity to our nine resident artists and to non-resident artists as well. So far, five artists have created original series of paintings or mixed media pieces based on our collections. Three of these were local artists selected by museum staff.

The fourth is the museum’s Community Artist in Residence, Curtis Woody. In his mixed media painting Quakers and the Challenges of Freedom, Woody juxtaposes the stories of Quakers freeing their slaves alongside images of freed blacks and segregated schools. It is a point of pride in Sandy Spring that the Quakers freed their slaves many years before the Civil War, but there is no public discussion of the fact that the community was segregated until it was forced to integrate in the late 1960s. As noted by Laura Koloski in “Embracing the Unexpected: Artists in Residence at the American Philosophical Society Museum,” artists can raise controversial subjects.[2] Seeing this subject for the first time in the museum when it is exhibited at the end of June may be jarring to some visitors, but we plan on offering programs that will allow for meaningful, in-depth discussion.

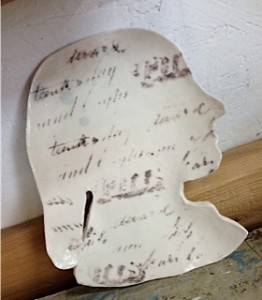

Porcelain plate with imprint of Fanny Pierce Iddings’ marriage certificate by Rikki Condon, 2014. Photo credit: Rikki Condon

The fifth, Rikki Condon , a member of the museum’s on-site pottery cooperative, found inspiration in the archives. While perusing the Pierce family collection, which has never been exhibited, Condon, a book conservator by training, came across an envelope of late 19th-century silhouettes. One in particular, the profile of Fanny Pierce, caught her fancy. She made clay pins with images of Fanny and then moved on to imprinting letters from the Pierce family on porcelain dishes. Because the Pierce collection also includes rag rugs, Condon is making small porcelain cups that mimic the rug pattern. Veering from pottery, she even created a cookie cutter identical to Fanny’s profile. In the future we plan to exhibit collection-inspired work of our resident artists in the museum.

The pottery studio is open to the public every day, so visitors can see works of art that were created in response to a family’s history, even when they can’t see the collection itself. But even more importantly to us, the visitors can speak with the artist who explains what she found in the archives and who the Pierce family was. Although we have not conducted a formal assessment, anecdotal evidence (judging from visitor traffic) suggests that far more visitors are drawn to a live artist than a static exhibit. We do not have the budget to have staff stationed in the exhibit discussing local history with visitors, but that’s exactly what Condon and the other resident artists do, essentially becoming historical interpreters.

While none of the artists are historians by trade, they have learned that working with the collection requires historical research, which they have conducted independently and with the help of the museum staff. The staff has, in turn, gained insight into what draws people to certain objects and what makes them want to learn more about that object. One conclusion is that allowing people to have direct access to the collection makes them want to learn more about local history.

Lifting the veil means that the institution has to be willing to show what’s behind the curtain and that the public has to be interested enough to take a peek. Opening access to our collection and providing visitors with the chance to speak with the people who are working with the collection are two ways in which we are facilitating this process.

~ Allison Weiss is the executive director of the Sandy Spring Museum.

[1] Weyeneth, “What I’ve Learned Along the Way,” 21.

[2] Laura Koloski, “Embracing the Unexpected: Artists in Residence at the American Philosophical Society Museum,” in Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2011).