Finding new value in Hartford’s voter registration records

12 March 2019 – Nancy Finlay

elections, Hartford series 2019, community history, archives, race, conference, gender/sexuality, Immigration, 2019 annual meeting

Voting Machine, Hartford, Connecticut, 1912. Image credit: Connecticut Historical Society

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of pieces focused on Hartford and its regional identity which will be posted before and during the NCPH Annual Meeting in Hartford, Connecticut in March.

The Hartford History Center at the Hartford Public Library houses some remarkable records pertaining to Connecticut’s capital. Collections such as the Town and City Clerk Archives (from 1639 through 1970) and the records of the Hartford City Parks Commission (from the 1850s through the present) contain a wealth of information about the city and its citizens. They not only detail Hartford’s rapid growth and cultural diversification, but also the changes in its physical structure, organization, and in its philosophical orientation over the course of several centuries. An important subset of these collections is Hartford’s Voter Registration Records, which cover the period from 1840 through 2009. A finding aid to these records was recently created and posted online in 2018. A small selection of the records was digitized at that time and funding is currently being sought to digitize records from 1900 to 1920.

The collection of voter registration records is divided into several series, related to the way in which voters were “made,” and the information that they were required to provide when they registered, changed over time. Generally, the complexity and density of the information on the cards increased over time, perhaps in an attempt to provide better documentation for immigrants, who had been a large part of Hartford’s population since the middle of the nineteenth century. Voter registration cards from the first decades of the twentieth century are a particularly rich source and include the date of registration, the name of the person registering, and that person’s address, place and date of birth, occupation, employer, and date of naturalization. Cards were updated over the years to reflect marriages and changes of address and occupation.

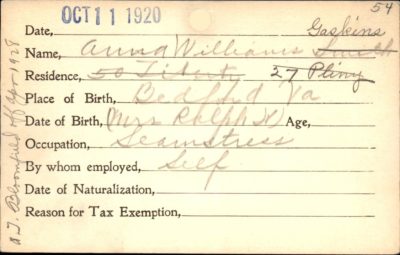

Voter registration card of Anna Williams Smith Gaskins. Image credit: Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

To better illustrate the type of useful and detailed information found on most voter registration cards, one has to look no farther than the record belonging to a woman named Anna Williams Smith. She registered to vote on October 11, 1920, just in time for the state and federal election on November 2. Her voter registration card shows a later change of address—from 50 Liberty Street to 27 Pliny Street—and a marriage—to a Mr. Gaskins. Her date of birth isn’t listed, but she says that she was born in Bedford, Virginia. Federal census records give Anna’s race as “colored,” “Negro,” or “Black,” and identify Mr. Gaskins as William J. Gaskins, who, like his wife, was born in Virginia.

For Anna Williams Smith, life in early-twentieth-century Hartford, as in other American cities, was one of dramatic change. It was during this period that women gained the right to vote in state and federal elections. Hartford women actually gained the right to vote in local school board elections in 1893, so women were registering to vote in the city throughout this period, but only in relatively small numbers. Their numbers increased dramatically with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the federal constitution in August 1920, however. The records of the Board of Selectmen (currently housed in Hartford’s Municipal Building but slated for transfer to the Hartford History Collection in 2019) reflect the urgent measures taken by the Board to accommodate this tremendous influx of new women voters. The records show that extra card writers were hired to fill out new-voter registration cards, and additional voting machines and “voting houses” had to be purchased. Members of the Board of Selectmen also staged instructional sessions to be sure that the women knew how to use the voting machines. In addition, on Election Day, the hours of the polling places were extended.

The early twentieth century also witnessed the arrival of large immigrant populations to Hartford. These populations included both foreign nationals as well as Americans arriving from other parts of the country, including many African Americans who came from the southern United States.

The presence of foreign-born immigrants is made evident in the collections by the listing of both place of birth and date of naturalization on the registration cards. A review of these records finds the huge proportion of foreign-born voters quite striking. This was the case not only between 1900 and 1920 but also throughout much of the nineteenth century. Many different countries are represented in the collection—not only in Europe but also in Latin America and the Middle East. The voter registration cards show that many of these immigrants found work in Hartford’s booming factories.

While it is easy to document some of the effects of women’s suffrage and the arrival of foreign-born populations by using the voter registration records, the task proves significantly more difficult when researching similar impacts made by the African Americans who moved to Hartford from the American South. This is because the detailed information on the voter registration cards of this period does not include the voter’s race. Identifying black voters requires cross-referencing the voter registration cards with federal census records, which include a category for race. With thousands of registered voters in Hartford during these decades, the process becomes somewhat tedious, but results so far are promising and suggestive. Once more records are fully cataloged and digitized, a more complete picture should begin to emerge.

Hartford’s Voter Registration Records not only make it possible to reconstruct the lives of individual Hartford residents, such as Anna Gaskins, but they also provide the raw material for tracking broader trends affecting local and national populations. The Hartford History Center is currently seeking funding to catalog and digitize the records from 1900 through 1920 and to make the digitized images of the individual records available online to researchers and the general public.

~Nancy Finlay grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. She has a BA from Smith College and an MFA and PhD from Princeton University. From 1998 to 2015, she was Curator of Graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society. She currently works as an independent contractor on projects in the Hartford History Center at the Hartford Public Library and in the Town and City Clerk Archives in Hartford’s Municipal Building.