History by design: a public historian in the creative field

25 November 2022 – Laurel Overstreet

I never thought of myself as a designer until recently. Design was the work of artists and architects, not historians. But when I graduated with my M.A. in Public History in 2020, it was not an ideal time to be seeking employment as a museum professional. After a long and often demoralizing pandemic-era job search, I landed at Luci Creative, an exhibit design firm that works on both cultural and corporate projects, as an exhibit developer.

Suddenly, I was encouraged to see myself as a creative in addition to an academic. My day-to-day work consisted of “design thinking,” which was not a type of magic or a mysterious art form, but a specific kind of problem-solving. As a public historian, I was uniquely equipped to solve certain kinds of problems.

Before starting at Luci Creative, I’d never considered putting my history degree to work at a design studio. Photo credit: Laurel Overstreet

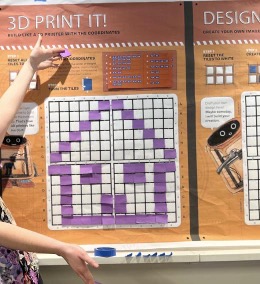

In many ways, the work I do as an exhibit developer at a design firm echoes the work of an exhibit developer in a museum. I create bubble plans that map out topics within an exhibit, prototype interactive elements, make outlines to keep track of content, and write labels and instructional text.

For one interactive-heavy exhibit, we pulled coworkers in as test visitors to see whether our designs could stand on their own and still communicate the points we wanted to make. Photo credit: Laurel Overstreet

Instead of working within a single museum’s subject area, however, my projects span a vast array of topics. I might spend the morning talking to the marketing team of a large company only to switch to writing a panel for a children’s exhibit in the afternoon. The variety in work tasks and exhibit topics is a major part of the appeal of the job for me; though I’ve been interested in history for a long time, I was always daunted by the idea of choosing a single focus. Of course, this variety comes with the caveat that I have very little choice over the projects I am assigned—instead of selecting my projects or even knowing the general subject area in advance, the projects that I work on may not have anything to do with my field of study, let alone my specific interests. There are occasionally also clients whose views of the past clash with mine, a conundrum not exclusive to public historians working for for-profit institutions.

Given the variety of exhibits and clients I work with, I’ve learned to adapt my public history training to projects that, at first glance, may have nothing to do with the past. Beyond just looking for the historical story in every project (although my colleagues will probably point out I do that, too), the skills I developed as a public historian apply even to the most science- or business-oriented exhibits.

In doing historical research, I learned how to formulate the right questions and search for the answers. Public history taught me to apply these skills to project life cycles, providing a framework for gathering context and strategies for managing large amounts of complex information. Research, project management, and communication are fairly standard transferable skills in the historian’s toolkit, but occasionally, the overlaps between public history and design work are more unexpected. More than once, I’ve used tactics from conducting oral histories and visitor surveys to draw out information from hesitant clients who may be unused to thinking like designers.

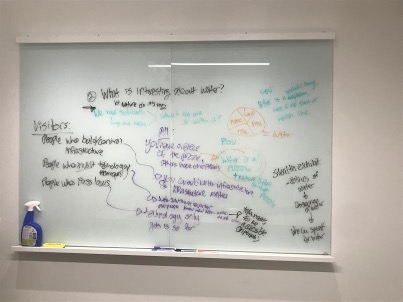

Nothing starts out looking organized. Like any creative process, exhibit design usually involves making a mess first. Photo credit: Laurel Overstreet

Of course, training in business, visual art, or psychology could help a designer develop comparable practical skills. Public history’s unique contribution to design work comes not just from the things historians learn how to do—important as those are—but the ways historians, especially public historians, learn to approach problems. Since design is a kind of problem solving, it helps to be able to understand and articulate the issue you’re addressing (the process philosopher Donald Schön called “problem setting”). Historians often turn out to be pretty good at this, trained as we are to search for context and identify patterns in data. This ability also becomes useful when it’s time to stop creating new ideas and synthesize possible solutions into a cohesive approach.

At the same time, design also requires divergent thinking, or identifying and holding many options, possibilities, and points of view simultaneously. Fortunately, at least in this case, contradiction and disagreement are often central to the public historian’s work. On the level of exhibit content, being able to balance multiple perspectives typically makes for a better, more nuanced exhibit. On a project level, it helps a designer manage the variety of expectations and needs that different people bring to the table. Public history’s ethical core provides a framework in which to evaluate all these opposing points of view.

As an exhibit developer, it’s not only my job to understand and represent the many perspectives visitors bring with them to an exhibit, but to help the client and the project team decide which perspectives to advocate for throughout the design process. When I speak to curators about their areas of expertise, I certainly empathize with the desire to convey as much nuance as possible in every exhibit element. On the other hand, I have also been the intern cutting and pasting labels on cardstock and trying to fit yet another panel on an already crowded wall. I’ve watched the visitor walk past the painstakingly designed interactive and skim over the carefully edited paragraph. Just as I don’t see complicated historical events as black-and-white object lessons, I don’t view the balance between accommodating the visitor and telling good history as a zero-sum game, but as a public historian I am empowered to make interpretive decisions that reflect the values of our field: inclusion, accessibility, and responsible scholarship.

Ultimately, an exhibit exists to help the visitor make meaning out of what’s in front of them, and design is the process of meeting that challenge. A hundred different visitors will create a hundred different meanings, and this isn’t a bug of good exhibits; it’s a feature. So the next time you need a creative eye to make order out of chaos, consider calling a historian.

~Laurel Overstreet is a Chicago-based exhibit developer and public historian. You can find Overstreet on Twitter and Instagram.