Incorporating labor history in a public history curriculum

11 August 2020 – Tracy Neumann

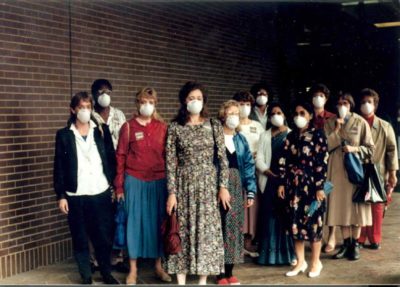

District 925 members at the University of Cincinnati demonstrating in 1989 for health and safety concerns. Photo credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Grassroots protest and union activism have flourished in the decade since the Great Recession. Labor and working-class history has flourished, too, and is experiencing a resurgent interest among scholars and public historians alike. At our particular historical moment, shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests against state violence and white supremacy, labor history provides context for urgent contemporary concerns about public health, workplace health and safety, economic inequality, structural racism, and social welfare. Asking students to research and interpret the diverse histories of working-class people for public audiences, either in collaboration with a community partner or through self-contained coursework, gives them the opportunity to help their communities understand the complicated history of race, class, and work locally and nationally.

Wayne State University, where I teach, is an urban public research university in the heart of Detroit. Labor history is one of the strengths of our graduate program, and we are lucky to have one of the world’s premier labor archives, the Walter P. Reuther Library and Archives, on our campus. We have also hosted, for forty years, the North American Labor History Conference. Our labor-related resources are unusually rich, but there are workers and working-class people whose stories remain to be told everywhere.

Scholars looking to kick-start labor-related public history initiatives might begin by taking stock of the existing resources on or near their campus. At Wayne State, faculty frequently build assignments around research at the Reuther. They also work with local cultural institutions, like the Detroit Historical Society (DHS) and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, on projects that document the lives of working people. One example is my own undergraduate general education course, The History of Detroit, which is also designated as a service-learning course. I typically engage undergraduates in community-focused projects that intersect with labor and working-class history. One semester, students conducted archival research and wrote short histories of sites significant to Southwest Detroit’s auto heritage under the auspices of a digital history project sponsored by MotorCities National Heritage Area, a National Park Service affiliate. Students documented companies’ efforts to fend off unionization by creating programs and subsidies for their employees. They wrote about strikes and they uncovered information about women’s struggles to secure childcare so they could work in auto plants. More recently, students conducted interviews with working-class residents of Detroit’s Mexicantown for a DHS oral history project documenting Detroit’s neighborhoods.

The Reuther provides my colleagues and me with an unparalleled resource, but of course, most colleges and universities do not have a labor archive on their campus, and faculty must look elsewhere for materials. However, university archives are likely to hold collections that intersect with themes of labor and working-class history to use as the basis of student projects and other forms of collaborative work. Absent campus resources, scholars eager to do public-facing work can partner with a local institution or organization that has existing community ties, both for practical reasons and in order to reinforce for students the high value public historians place on community engagement and a shared authority. Public libraries, historical societies, and history museums are likely repositories of records and artifacts related to labor and working-class history, and they are typically staffed by people who value student engagement and have an interest in collaborative projects and programming. Reaching out to local archivists, curators, or research directors at these kinds of institutions to inquire about their holdings related to, and their interest in collaborating on, projects interpreting labor and working-class history is one way to get started. Outreach officers or grants coordinators for state humanities councils are good sources for learning about projects that may already be in the works. And the Society of American Archivists’ Labor Archives Section is an excellent resource for finding relevant archival collections and archivists with a particular interest in labor history. Finally, the NYU Libraries has an excellent guide to digital resources related to labor history, which might inspire project ideas, long-distance collaborations, or provide access to primary sources.

Working with community partners makes labor history more interesting to and relevant for students (and faculty) by showing them that public history projects have stakeholders beyond the academy and museum audiences. It also broadens students’ conceptions of labor history. Many students have internalized contemporary imagery of “workers” as white men who build cars or mine coal. These tropes have been perpetuated by national media outlets and politicians even as the labor movement in the United States has increasingly come to be dominated by women and people of color employed in the service industry and helping professions, as we saw with the Fight for $15 and a recent wave of teachers’ strikes. When students conduct oral histories with working-class residents, create exhibits, or write material for websites about regional labor history, they learn that labor history is the history of a diverse group of Americans. Perhaps most importantly, contributing to public-facing projects with faculty and community partners teaches students that labor history matters, and shows them how to communicate its significance to a general audience.

As many educators prepare to move their courses online in whole or part, in-person collaboration with community partners may not possible for the duration of the pandemic due to site closures or lack of capacity at institutions that do remain open. This should not dissuade instructors from pursuing public-facing projects that engage labor and working-class history. Students might, for instance, create digital tours of local labor history sites using Google maps or Clio (or Story Map, for a more ambitious project like the New York City Labor History Map). They could curate digital exhibits to tell stories about diverse working-class people whose experiences are not presently well-represented in the digital sphere, a project which could involve collaboration with a library or museum, locally or nationally. In a moment of national reckoning with the United States’ historical monuments, students might be particularly interested in exploring ways to incorporate labor and working-class history into their region’s commemorative landscape. To offer a local example, the recently-removed statue of the longtime segregationist mayor of Dearborn, Michigan, Orville Hubbard, might inspire students to investigate the extent to which the experiences of African American and white Southerners, Arab Americans, and Mexican Americans who came to Dearborn and Detroit to work in Henry Ford’s massive Rouge plant are—or not—reflected in the city’s public spaces, and not just in its museums.

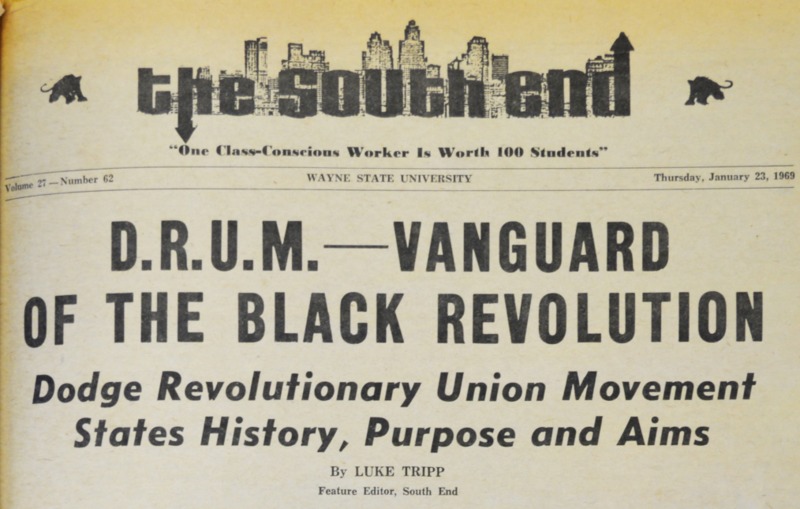

Wayne State University’s campus newspaper coverage of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement. Photo credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Public historians have an important role to play in disseminating narratives of American labor history that emphasize the struggles and contributions of workers of all races, genders, and sexual orientations and privilege the experiences of teachers, nurses, and farmworkers as much of those of miners, autoworkers, and steelworkers. And these are the kinds of stories students find most engaging: stories that challenge what they think they know and ask them to see the world around them through different eyes. Learning, for example, that Southwest Detroit is home to one of the oldest Mexican American neighborhoods in the Midwest, the settlement of which dates to need for workers in the auto industry the 1920s, or that our university’s student newspaper was briefly something of a house organ of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, an organization of radical black autoworkers, broadens’ students understanding of whose history is part of labor history.

The public histories of labor to which students contribute also perform a vital role by helping workers connect the past to present-day struggles. Telling these stories now seems more pressing than ever, when not just nurses, but grocery store staff and delivery drivers and teachers find themselves classified as frontline workers and a Strike for Black Lives highlights just how many of our essential employees are also victims of systemic racism. Many public history educators are planning to marshal students to collect interviews for COVID-19 oral history projects, which will document and preserve for the historical record the experiences of these new frontline workers. Others, particularly those who are struggling to develop publicly-engaged projects at a time when face-to-face interaction and research is limited, inadvisable, or impossible, might consider using public history tools to investigate workers’ responses to previous public health crises and use them to support contemporary organizing efforts.

~Tracy Neumann is associate professor, director of graduate studies, and director of Public History and Internships at Wayne State University.

This sounds great! Years ago, when I worked for the House of Representatives Subcommittee on National Parks, we pushed the National Park Service to do a Labor History Theme Study– the NPS only wanted to include organized labor. Having just finished Doing Women’s History in Public: A Handbook I have come to realize even more than already how much labor is unrecognized, unpaid, and not included: the labor by women. The men who worked in the mines, mills, and offices had women who filled their lunch buckets, washed their grimy clothes, and ironed their collars, not to mention all the other crucial things women did. Women of color often did the most grueling work in agriculture, industry, laundry, etc. We must fully include the labor of everyone.