Looking for Lucille’s story in the 1950 census

16 June 2022 – David Rotenstein

On the morning of April 1, 2022, I was among throngs of remote researchers who visited the National Archives and Records Administration website to access data from the newly released 1950 Census. I had waited thirteen years to answer one research question: Who was the Black woman working in a family home that I had first researched in 2009? I found her quickly on that spring morning after I entered the family’s name and location into the website’s search form: Lucille Walker, a 40-year-old Tennessee native. This essay explores the intersections of collaborative research, social history problems, and the newly released census forms as a window into segregated residential subdivisions. The data offers historians opportunities to decenter the white developers and homebuyers who dominate much of the existing literature on suburbanization in the United States.

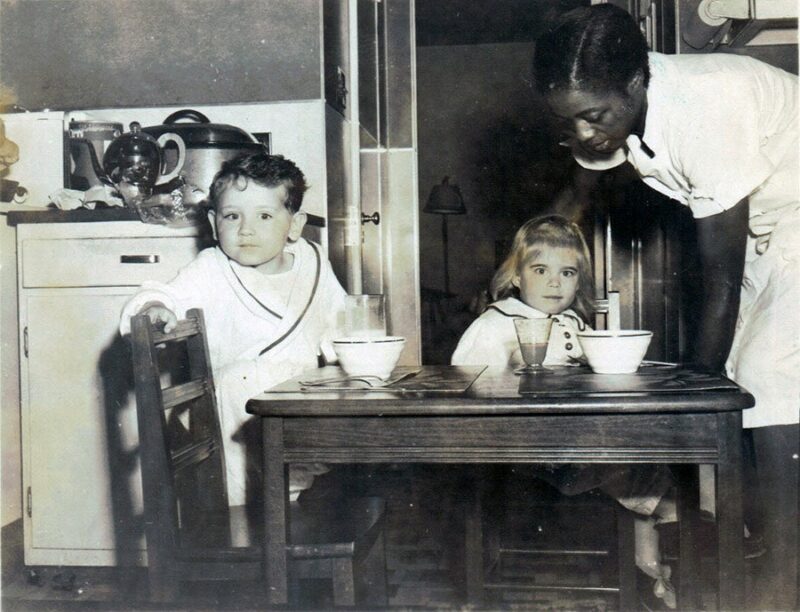

Lucille Walker at the Scandiffio home, Silver Spring, Maryland, circa 1950. Photo credit: Pauline Scandiffio Used with permission of Ann Scandiffio

Walker’s identity had been an unanswered, and potentially unanswerable, question when I was first researching the history of a home in my neighborhood in Silver Spring, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C. I lived in a residential subdivision laid out in 1936. The developers launched their annual sales campaigns around model homes tied to a theme, and a modest Cape Cod home a block away from my own had been their 1939 model home. To better understand the home’s history and its first owners, I tracked down their daughter, Ann Scandiffio, who lived in North Carolina.

In 2009, Scandiffio could only remember her family’s housekeeper’s first name, Lucille, and the name that she had called her as a toddler: “Sha.” Finding Walker’s full name and additional biographical details offered me a chance to revisit my earlier research, which had focused on developers who reproduced one of the homes in the 1939 World’s Fair Town of Tomorrow.

Former Scandiffio home/1939 World’s Fair Home, Silver Spring, Maryland, 2009. Photo credit: David S. Rotenstein

The 1950 Census release gave me a chance to reconnect with Ann, who also used the data that first day it became available. After a decade of work documenting erasure and racism in historic preservation, I had different questions about the Scandiffio family home, centering on the white family (the Scandiffios) who bought the home in a racially restricted subdivision (developed in a sundown suburb) and the Black woman (Lucille Walker) who lived with them.

Black in White Space

Ann Scandiffio’s parents, Mario and Pauline, bought the house in August 1939. He was a pediatrician, and she was a former federal employee and nightclub singer. Like many homes built and sold in the United States before 1948, their new home had a covenant attached to the deed prohibiting all but persons of the “White or Caucasian race” from buying or renting the property.

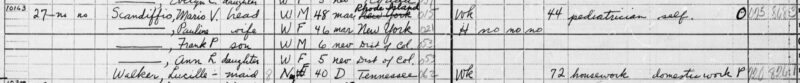

There were 207 homes, housing 723 people, in the Northwood Park neighborhood in 1950. Only three of these people were not white: a Chinese newspaper correspondent and two Black women working as housekeepers, Lucille Walker and Blanche Young. Northwood Park and its counterparts throughout the nation were white spaces, devoid of Black people.

Scandiffio family photos taken between 1944 and 1951 show Walker caring for Ann and her older brother in the house and yard. “I know she was there every night,” Scandiffio told me in a telephone interview three days after the census data release. “I don’t remember [that] she left the house, you know, to go visit family or something like that.”

Except for the 1950 Census, Lucille Walker is invisible in Northwood Park’s history. Yet, she and the scores of other Black women who “lived in”—residing in their employers’ homes—were integral members of twentieth-century urban and suburban households. Looking for and recovering their stories in white spaces has been one of my research objectives since I began examining suburban gentrification and erasure.

The Census Opens Doors

In 2022, many of the people in the 1950 Census can still tell their own stories of life during Jim Crow segregation. Ann Scandiffio was five years old when enumerator Mary Kelso knocked on her family’s door and about seven when her family moved to Florida in 1951.

Lucille Walker with Frank and Ann Scandiffio, circa 1950. Photo credit: Pauline Scandiffio Used with permission of Ann Scandiffio

Armed with Lucille Walker’s name, my questions opened more of Scandiffio’s memories. She recalled that Walker traveled with the family to their summer home in East Hampton, New York. Talking about race jogged another memory about the time Scandiffio’s family came back to Washington for a visit.

“We stayed at the Dupont [Circle] Hotel,” Scandiffio recalled. “And when [Walker] came to visit us, there was a big hullaballoo in the lobby because she was Black and they didn’t want her to go upstairs. My father went down and little guy as he was, he was very forceful about that. And he took her upstairs to our room.”

That one-hour visit was the last time Scandiffio saw Walker. Years later, her parents told her that Lucille had died of cancer. Over the course of our recent interview, Scandiffio recalled other details about Walker and the Scandiffio family household.

For instance, the census noted that Lucille had been divorced in 1950. “Her husband was, I believe for a while, a handyman for us. But then evidently when they divorced, that stopped,” Scandiffio said.

Lucille Walker can no longer tell her own story. The only evidence of her years living with and working for the Scandiffios is limited to distant memories, family photos, and a single line in a census population schedule denoting her relationship to them, occupation, and industry: “maid, housework, domestic work.”

Scandiffio household, 1950 Census. Screenshot, Official 1950 Census, National Archives and Records Administration website

Intersections

Beyond the white space lies Black space: the African American enclaves and neighborhoods on the sundown suburb’s margins. Interrogating the census is an opportunity to shed light into the gender, race, and class relations in segregated suburbia. In these Black spaces, women and men who identified themselves to census takers as “domestic workers” and “gardeners” comprise a mostly unexplored dimension of suburban history. My search for Lucille Walker’s story isn’t over, nor is my desire to better understand suburbia’s full history. It’s a challenge to myself and other historians to interrogate twentieth-century segregated spaces for information concealed by erasure and hidden records.

~David S. Rotenstein is a public historian and folklorist based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He writes on gentrification, erasure, and historic preservation and is a tour designer and host with Doors Open Pittsburgh.