Making digital space for Latino community histories

12 May 2022 – Yazmin Gomez

oral history, Digital humanities, covid-19, Labor History and Digital Humanities Series, Latinx history

Editors’ Note: This is the second of four essays in a series on labor history, digital humanities, and public history. Authors who wrote essays for this series developed their work as part of a fall 2021 graduate labor history colloquium taught by Dr. Andrew Urban at Rutgers-New Brunswick.

I am interested in how the digital humanities can be utilized by Latino communities to share new stories that have long been ignored. What projects are being developed to do this? What is their impact on teaching and research? In this post, I discuss my experiences with various digital efforts to share Latino experiences with the public.

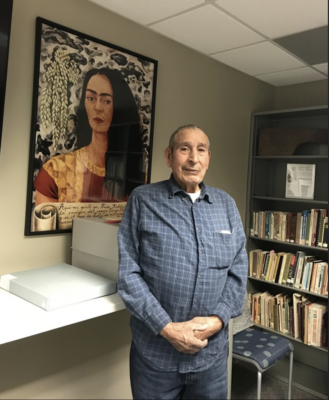

On a recent archival visit to the University of Iowa, I encountered the story of Raymond Martinez who, on his ninetieth birthday, brought his family into the library to see their history housed there. His parents arrived in the Midwest in the 1920s and quickly became part of the growing Latino community. Martinez’s younger sister, Adella, had donated 100 years of family documents and provided an oral history to the collections. Looking at childhood photos of himself in the archives, Martinez expressed great pride in his family’s contributions and hoped they leave a lasting legacy for the public who encountered these records. This story of a man I never met stayed with me as I explored the archives, both in-person and online, of community activists.

Raymond Martinez on his 90th Birthday at the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA) in Iowa City, Iowa. Photo credit: IWA staff.

Public historians often aim to produce scholarship through rich community engagement. Whether through the creation of oral histories, publicly shared exhibitions, or educational curriculums, there are many ways in which scholars can make their work relevant to public audiences beyond university campuses. Digital initiatives have shown fruitful avenues for sharing research. Yet who benefits from these efforts? How can publicly engaged historians and communities utilize the digital humanities? How do they influence the teaching of history? What are the challenges of online projects? These questions and more arose after a recent digital humanities workshop with other Rutgers Ph.D. students.

As I work, I have adapted to the ever-evolving digital landscape. Take for instance the production of digital oral history projects. In oral history, one’s life story or experience of a specific historical event is chronicled in an interview. These often take place in person with a recorder producing an audio version while the interviewer takes notes. However, this is changing. Early last year, I conducted an interview with Debora La Torre, a New Jersey nurse grappling with the pandemic. Given the circumstances, our interview took place via Zoom, yet the physical distance did not diminish the quality of our time. Technological advancements that allow connections across geographies and time zones have expanded what oral history can look like. Yet barriers to documenting such important histories exist. For instance, I have heard tales of video files disappearing from the cloud and limited access to technology, especially for low-income or elderly individuals.

Higher education has been slow to adopt the digital humanities into pedagogical practices. For example, university graduate programs remain hesitant to stray from traditional training in teaching, archival research, and academic writing, and only some have begun offering certifications or minors in digital humanities. Because of this, students are not always aware of the innovations of history and may feel that the academy has discredited new fields and stories.

Aware of these hurdles, community activists and academics alike have begun to respond with their own proposed curricula rooted in community research. Alongside oral histories, these curriculum guides are powerful tools that function to educate and also institutionalize community knowledge. For example, the Wisconsin Latinx History Collective, a project I hope to contribute to, is a coalition of scholars, activists, and community members. Their mission seeks to “retrofit” Latinx experiences within “the Wisconsin historical narrative.” Founded and led by residents turned scholars, the multiyear project will share long-ignored histories with educators via oral histories, mapping, and classroom guides. Although it is still in its infancy, the project has already produced demographic information and identified subjects of interest throughout the state.

The Wisconsin Latinx History Collective, founded in 2021, has partnered with scholars and community members around the nation.

This and other new public-facing research projects, like Latino Wisconsin and Somos Latinas, are operating in a changing academic and social landscape. Their innovations give glimpses of the future of public and digital humanities. The rise of the digital humanities has been praised as empowering to marginalized communities, but scholars and community members alike need to be aware of the potential pitfalls of recent developments. Being aware of how best to incorporate digital methods can allow for even more robust and engaged scholarship.

~Yazmin Gomez graduated from Marquette University with a bachelor’s degree in history and psychology and is currently a Rutgers history Ph.D. student. She specializes in the history of Latinos, women’s activism, and the Midwest during the late twentieth century.