National Women's History Museum & material culture wars

23 May 2014 – Manon Parry

Sonya Michel’s recent post brings the behind-the-scenes issues that have plagued the National Women’s History Museum (NWHM) project for years into public view. In 2012, when the Huffington Post reported “National Women’s History Museum Makes Little Progress in 16 Years,” it listed a catalog of concerns, from the overblown CV of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) to financial irregularities. In fact, long before this recent crisis, historians were invited to join the original advisory board, only to be dismissed, along with all of their recommendations [see comments].

The consequences have been profound. While CEO Joan Wages may not think historians are integral to the project, the resulting online exhibitions, labelled “amateur, superficial, and inaccurate” by Michel, are certainly disappointing, mixing trite sentimentality (“Profiles in Motherhood”) with shallow celebration (“Daring Dames,” and “Young and Brave: Girls Changing History”). As the Huffington Post article noted, “there appears to be little rhyme or reason to who or what is featured on the museum’s website.” Yet despite the upbeat tone and narrow emphasis on great women and their accomplishments, the exhibitions are still too provocative for the right-wing opponents of women’s history. Since 2008, legislation to grant NWHM permission to build near the National Mall has stalled six times, blocked in Congress by Republican opponents acting on behalf of anti-abortion interests. Michele Bachmann’s charge that the museum will create an “ideological shrine to abortion” is just the latest in this repeated strategy. In 2010, Tom Coburn (R-OK) and Jim DeMint (R-SC), placed a hold on a bill two days after Concerned Women for America requested one, claiming that the museum would “focus on abortion rights.” In response, Wages reassured opponents that reproductive health will never be tackled in the museum. “We cannot afford, literally, to focus on issues that are divisive.”

I know first-hand that the content of the museum’s website owes more to the fears of a political backlash than to the results of decades of groundbreaking historical research.

I completed my PhD in 2010 with Sonya Michel as my dissertation advisor. Interested in employment opportunities at the NWHM, I arranged an informal phone conversation with a staff member at Ralph Appelbaum Associates, then involved as designers for the project. Although this contact acknowledged my relevant training and expertise, she bluntly stated that my research, on family planning media over the twentieth century, made me a liability, given the political sensitivity of the topic. Birth control may be legal in America today, but it is clearly not legitimate. I mention this personal anecdote as full disclosure, not to complain about what happened to me, but to highlight how bad things have become. This is the state of the public history of women in twenty-first century America. Simplified, politically sensitive, and censored.

Despite the weaknesses of shutting out a major aspect of everyday life by excluding reproduction, the point is, of course, that the whole concept of the museum is divisive, as well as every aspect of what it will include. In the decade when I was working as a curator in Washington, DC, colleagues at various institutions, including the Smithsonian and National Park Service as well as universities and private museums, disagreed on the merits and limits of a National Women’s History Museum. Some thought women’s history should be better integrated into existing museums and not treated in a separate space, while others supported a dedicated institution with the prestige of a national identity but worried about the quality of work in a private project. All raised questions about the kinds of histories that would make the cut.

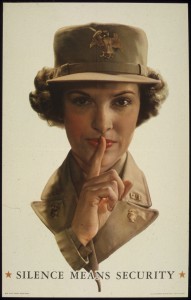

These divided opinions are not a problem but instead create productive discussion–which is vital for public history practice. As recent posts on this blog have argued, gender and sexuality are not optional elements for understanding the past but are instead categories as crucial as race or class. Truly integrating gendered analysis in public history projects means more than adding in a few famous figures or focusing on so-called “women’s issues.” It means fundamentally reconstructing our approach to sources and the stories they reveal. We need to bring these issues out into the open so we can consider how we are incorporating women’s history elsewhere and why there might still be a need for a new museum. We should explore strategies to connect with diverse audiences, bringing women’s history to people who question its value. We must foster discussion and air disagreements so we can demonstrate how historical knowledge is produced and validated. Now that this latest controversy has erupted, we need to ask voters, and their political representatives, if they agree with the CEO of the NWHM that the solution to the reignited culture war is silence.

In the coming months, as guest editor of a special issue of The Public Historian on women’s history, I will be gathering contributions from public historians in the US and around the world for a series of essays investigating the ways in which women’s public history is inflected by the politics of gender in society. I hope this international comparison will allow us to take stock of the serious issues we still face in making women’s history a part of standard public history practice.

Please join the project by sharing your ideas for exhibition reviews, blog posts, and events and extend this invitation to others. You can reach me via email or at the Berkshire Women’s History conference in Toronto this week. On Saturday 24 May from 8-10 am the NWHM will be one of the discussion topics in the session Women’s History Meets Public History. Don’t miss it!

~Manon Parry is Assistant Professor of Public History at the University of Amsterdam and the author of Broadcasting Birth Control: Mass Media and Family Planning (Rutgers University Press, 2013).

I am speaking for myself and not NWHM…but as one of the founders I know the full history of what NWHM has done.

It is amazing to me that folks whose profession calls for historical accuracy have said some of the most inaccurate things about this effort; this author for example never picked up the phone to check her facts before writing this piece.

But let me be more specific…Never has anyone associated with the National Women’s History Museum EVER said in public or private, that historians are not integral to their work. They have employed historians to either write, edit and/or thoroughly vet every exhibit, or educational resource, they have on their site. That site is by no means complete and in fact most of the biggest subjects are not yet up (some are in process) since they require more time and money than was available previously. In fact their biggest critic, Sonja Michel authored their piece on Jewish women. The subjects covered so far were chosen for specific reasons and I will leave it to NWHM to give the official explanation. There was rhyme and reason to why each went up when they did…but Sonja and other critics did not ask. It is sad that so much disinformation has been put forward by people with an agenda.

All of these public attacks only serve to support those very conservative critics and misogynists who never want this Museum to be able to secure a site on or near the Mall… That is its rightful place, at the center of our Nation’s Capital where we as a Nation show what we honor. But it will never happen if folks who should be our allies spend all their time trying to tear NWHM down.

Our group National Women’s History Museum has done the hard work of raising this need for women’s history, passing the legislation and raising the money first to move the Portrait Monument given to Congress by the Suffragists in 1920 into the Rotunda and now to raise money for ongoing programs, lectures, speakers, traveling exhibits and to pay for a National Commission to find us a site on or near the Mall.

We are paying for that Commission and will pay for the building of the Museum. Some have criticized us for that. But consider these two reasons….first with a 17 Trillion dollar Federal debt there would be no Federal funding…but there is a bigger reason…we as women have always been the ones to push for and fund historic preservation for everyone and everything else. Don’t we deserve this Museum and shouldn’t we show we can do this for ourselves?

When it is done this Museum will be the largest capital project ever undertaken by women, for women nationwide. That alone will send a powerful positive message to hit back at those who would tear down and denegrate women. I hope this author will realize she has be somewhat misled and mistaken and join with us to help and not hinder making this Museum a reality.

This weekend at the Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, I attended two sessions on the NWHM. Joan Wages and Sonya Michel participated in both, and can be commended for continuing to engage despite the recent difficulties. Wages and several of the historians formerly involved in the scholarly advisory council acknowledged mistakes made on both sides, including, critically, failing to invite peer review of exhibition scripts, and failing to provide it on materials that were circulated.

It is clear that academic historians are still interested in helping to realise the project. The smaller group of public historians who were at the conference are also interested – as are many in the NCPH community (hence the attention to the issues here on the blog). Overall, all recognise the difficulties the NWHM team have faced due to the hostility of right-wing opponents and a minority of politicians.

Some core issues came up at the sessions as we debated how to move forward:

-To formally institute peer review on all historical content and to employ a qualified, experienced historian to develop exhibitions. Some have asked for a PhD historian to be added to the staff – but an experienced public historian, with or without a PhD, is vital. As those who have worked both in academia and museums acknowledged, there are different approaches to sources, stories, audiences, and communities (including stakeholders in government, professional advisors and lay contributors), that exhibition work requires, and which would be very useful. However, as the difficulties within the scholars advisory council demonstrate, history by committee is hard, and rarely results in compelling exhibitions. While scholarly committees can play an important advisory role, a smaller team of subject specialists (who change depending on the topic of the exhibition), would be most useful for providing timely peer review – and an experienced and confident curator could help manage that process and determine if, and how, specific feedback needs to be incorporated.

-To reconsider the focus on working with federal funding but building on federal land. To embrace federal funding would also mean federal oversight – improving the credibility and accountability of the proposed institution among historians as well as politicians of all persuasions. Alternatively, finding a non-federal site to build on would free the museum from the current political tug-of-war and allow them to move forward without the kinds of comprises in content that are currently causing such concern.

-To rethink the strategy of avoidance/compliance in response to political opposition, and to instead tackle the critics head on. The museum is already heavily politicised, and shying away from certain topics will not solve that. Confronting the opposition could help to marshal public support for complex histories that include the spectrum of political views and demonstrate the variety of issues and motivations that have shaped everyday life for women in the past and in the present.

All of us who care about the future of women’s public history have a role in this – for a start we need to diversify the range of voices in the debate (within the museum, in the blogosphere, and in the public debate). In the process, we would generate new ideas that could lead to a better museum, and/or to better women’s public history in other venues. We could also prevent a minority of politically-motivated opponents from highjacking the entire project – but only if more of those reading about this controversy will speak up. Comment here, discuss the issue with your colleagues, and make sure your political representatives hear from the broader community of people invested in women’s history.

Manon S. Parry, University of Amsterdam

Thanks, Ann and Manon, for these thoughtful comments. And I’m glad to hear that Joan Wages and Sonya Michel are continuing to engage with one another despite the fraught situation surrounding the museum. Reading about it over these past couple of weeks, I’m struck by the way that this all seems to be as much about publicness–public funding, commitment to creating shared spaces for substantive debate and dialogue, etc.–as about particular ways of approaching women’s history. The fact that there is civil discourse going on about this here and elsewhere seems to illustrate the point that Sonya, Manon, and others have been trying to make – i.e. that it’s crucial to create room for unfinished and multivocal narratives about the past (and the present). That is of course a key tenet of feminism, and it seems to me that it’s alive and well within the larger debate if not yet within the offerings of the museum itself!