Our Side of the Tracks: Community Curation of Black History in Acworth, Georgia (Part 1)

02 March 2021 – James Newberry

The first of two installments in a series exploring the development of the “Our Side of the Tracks” exhibit at Doyal Hill Park in Acworth, Georgia, Part One describes the origins of the project, starting with the partnership between Kennesaw State University’s Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books and the City of Acworth, Georgia, as well as providing background on developmental changes over the past forty years in Acworth’s historically Black neighborhoods. Part Two will explore the outreach phase of the curatorial process, which built on initial research and ultimately turned the exhibit in a new, more personal direction.

Acworth City Alderman Tim Houston speaks at the dedication of Doyal Hill Park in December 2020. Photo credit: City of Acworth

“A lot of African American history has not been told or been left out of the history books,” said Acworth City Alderman Tim Houston at the opening of Doyal Hill Park in December 2020. “What we’re doing today as a community is acknowledging and preserving our history.” Houston’s words capture the significance of the Doyal Hill Park project, which represents one step in an ongoing effort to save what remains of Acworth, Georgia’s historically Black neighborhoods northeast of the railroad tracks.

Starting in June 2020, the Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books (MARB) at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia, partnered with the city of Acworth, Georgia, to develop a permanent exhibit exploring the city’s historic Black community in the century and a half after the Civil War. Opened in December 2020, the permanent, panel-based exhibit, titled “Our Side of the Tracks,” is part of Acworth’s new Doyal Hill Park at the geographic center of the city’s historically Black neighborhoods.

The result of six months of research, community outreach, and production time, “Our Side of the Tracks” includes seven panels installed along a path running from the sidewalk along Acworth’s Cherokee Street to the Rosenwald School Community Center.[1] The panels explore topics related to business, society, religion, education, and recreation in Acworth’s historic Black community through narrative text, quotations, and imagery—including photographs, newspaper articles, and documents—as well as supplementary captions.

My part in the Doyal Hill Park project began last summer, when Acworth’s Parks, Recreation, and Community Resources Director contacted my office in the Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books (MARB). As part of my work for MARB, I develop local exhibits, archival collections, and education programs with my colleague Research Specialist Kelly Hoomes, a former recreation leader in Acworth. We began work on the Hill Park exhibit in June as the COVID-19 pandemic raged and protests over police shootings of Black men and women challenged the nation’s conscience.

For our research, we drew on materials provided by the city of Acworth, property records, historic newspapers, local archives, and a number of oral history interviews previously archived at Kennesaw State. We consulted colleagues across our department, including Special Collections Curator JoyEllen Williams, who works to diversify the holdings of the university archives and the Bentley Rare Book Museum—both units in MARB—through the addition of Black and Brown voices and student instruction and engagement. Williams secured the donation of three archival collections documenting the history of African Americans in Marietta, Georgia, and has spearheaded the purchase of rare books by Black women writers.

Our team drew on previous scholarship by Patrice Shelton Lassiter in A Place to Remember: A Journey of African Americans in Cobb County, Georgia, Featuring the City of Acworth and Generations of Black Life in Kennesaw and Marietta Georgia. Kennesaw State Professor Emeritus Dr. Tom Scott, author of Cobb County, Georgia, and the Origins of the Suburban South, reviewed exhibit text and connected us with former student Camille Kleidysz-Ferreira, whose master’s thesis, Secrets on Morgan Hill: A Story of an Unlikely Friendship Amid an Apartheid South, offers a fictional narrative inspired by true events in Acworth in the early twentieth century.

Assembled guests unveil the “Our Side of the Tracks” exhibit at the dedication of Doyal Hill Park in December 2020. Image credit: Kennesaw State University Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books

The city of Acworth established a small, multiracial group of public officials and local historians, who had worked on previous community exhibit and education programs, to review exhibit content before and after the design phase. Our most valuable source was a sprawling community of current and former Acworth residents, who chatted with us over the phone or hosted us for socially distanced visits on porches, carports, and driveways. Throughout the course of developing the exhibit, we contacted over fifty individuals and visited fifteen across Metro Atlanta. Their contributions would come to define the “Our Side of the Tracks” exhibit.

Located thirty miles northwest of Atlanta off Interstate 75, Acworth is one of the fastest-growing cities in Cobb County with a population of over 22,000. The city’s economic dynamism reflects the impact of downtown revitalization efforts started in the 1980s, when the population hovered at 4,000 and Main Street businesses languished. Proposals for faster interstate access threatened homes in historically Black neighborhoods northeast of the railroad tracks and spurred long-term waves of redevelopment that would reshape the built environment in the following decades. As local officials and community members debated questions of displacement and quality of life in the early 1990s, longtime resident and city employee Amos “Deacon” Durr told a reporter with The Atlanta Constitution, “I’m not against progress—I’m even willing to be ground up under the wheels of progress, but just be sure it’s progress.”

Acworth’s historic Black community developed northeast of the railroad tracks in the decades after the Civil War, as freed people forged connections through churches, small businesses, and leisure time. Two churches, Bethel A.M.E. and Zion Hill Missionary Baptist, provided a source of social cohesion that persists in the present, even as many longtime members live elsewhere. In the mid-twentieth century, Black-owned restaurants such as Price and Lucy Mae Oliver’s School Street café, Lula Morris’ “Sandy Bottom” juke joint, and John Buffington’s ice cream parlor, offered an alternative to Main Street’s whites-only establishments.

The Rosenwald Fund, financed by Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, between 1917 and 1948, built schools for Black children across the South and funded a variety of other philanthropic causes for “the well being of mankind.” Rosenwald contributed funds for three Black schools in Cobb County including Acworth’s 1924 Rosenwald “Colored School,” where teachers led elementary and middle-school age students in morning devotions, lessons in writing, arithmetic, and geography, and school fundraisers. If Black students wanted to attend high school, they had to travel to Marietta or Atlanta. When the school board voted in 1949 to build a new brick facility or equalization school, later known as Roberts School, in place of the Rosenwald “Colored School,” the Black community took ownership of the old wood frame structure. “I remember children and women in the hot sunshine pulling nails,” said Deacon Durr, who coordinated the effort to deconstruct the building and rebuild it on Cherokee Street, where it stands at the center of Doyal Hill Park today.

City Alderman Tim Houston long dreamed of the Hill Park site as a place to commemorate the early history of Black people in Acworth and serve as an anchor for the community’s remaining landmarks. Growing up in the community in the 1960s, Houston saw the impact of Acworth’s economic decline on his neighborhood, as old homes gave way to neglect and demolition and young people sought opportunity in other parts of Acworth and throughout Metro Atlanta. After Roberts School sat dormant in the years following integration, Houston led a successful effort to save the facility and convert it into a community center in 2000.

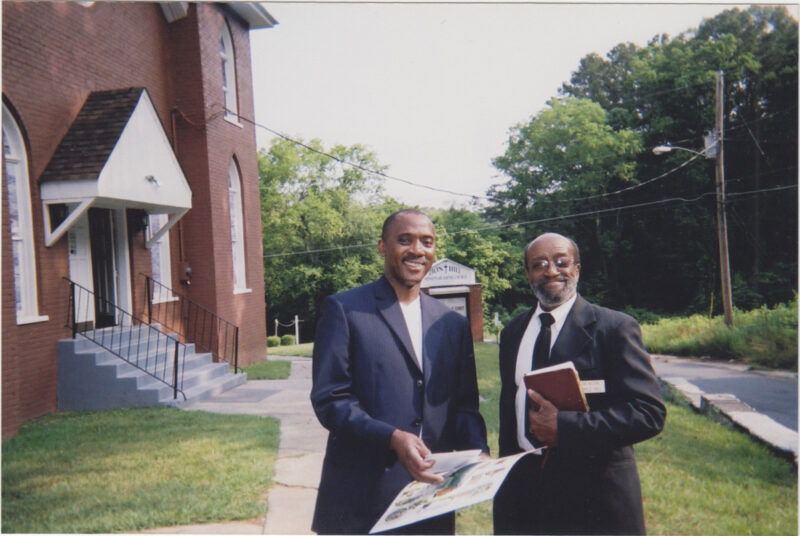

Doyal Hill, Acworth’s first Black elected official (right), and Pastor Frank Johnson, Jr. in front of Zion Hill Missionary Baptist Church, Taylor Street, Acworth, Georgia, 2007. Photo credit: Kennesaw State University Archives

Houston’s half-brother Doyal Hudson Hill was the first Black elected official in Acworth. His path from a sharecropper’s farm to five terms on the city’s previously all-white Board of Aldermen showed persistence and grace. “Dad always made it sound like everybody embraced him,” said Hill’s son Eugene, from his home in Fairburn, Georgia. “Dad just didn’t notice obstacles. I don’t think I could’ve done it, but he was old school.” Eugene shared photographs of his father as a younger man whose pursuit of Black representation in local government would come to equal his long-term engagement with the needs of his community.

Doyal Hill tested Acworth’s at-large voting system when he chose to run for a seat on the all-white Board of Aldermen in the early 1980s. He won on his second attempt with the support of Black and white voters, and many community members now view his efforts as central to overcoming Acworth’s symbolic color line, the railroad tracks. As Alderman Houston said at the dedication of Hill Park, “I can’t think of a person more deserving to be honored than Doyal. They used to give him the nickname, The Bridge. He would always fit in where nobody would fit, to help carry us over.”

~ James Newberry is Special Projects Curator for the Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books at Kennesaw State University.

[1] Acworth, Georgia, sits on land taken from the Cherokee Nation after the U.S. Government forcibly removed native peoples in the 1830s.