Preservation, rehabilitation, and interpretation as agents of transformation along the New York canal system

14 February 2018 – Brian Yates

Editor’s note: This is the sixth in a series of posts on deindustrialization and industrial heritage commissioned by The Public Historian, expanding the conversation begun with the November 2017 special issue on the topic.

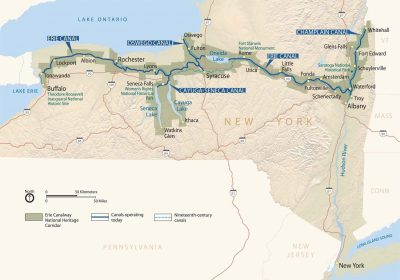

The Erie Canal system. Image credit: Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor.

An increasingly evident legacy of deindustrialization sprawls across New York State. In industrial centers such as Buffalo, Rochester, and the Greater Capital Region of Albany, Troy, and Schenectady, the effects of loss of industry along the New York State canal system are easy to see. Smaller communities (many located throughout the Mohawk River Valley) also experienced deindustrialization and lost major industries that once supported significant portions of those communities. Towns and villages such as Canajoharie, Amsterdam, Cohoes, and Lansingburgh lost iron mills, carpeting and garment factories, and other manufacturing facilities. Quietly, many sites and structures have survived to form part of the rich physical legacy of industry, each with varying levels of interpretation, but still standing as part of the industrial and deindustrialized landscape.

There are many challenges to interpreting industrial heritage sites across the northeastern United States. However, there are also notable examples of initiatives that provide models for interpreting sites that might otherwise be lost to the effects of deindustrialization. Among these are the programs administered by the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor Commission, in partnership with the Erie Canalway Heritage Fund, the nonprofit that works with the federally appointed commission, the National Park Service, and numerous local, state, and federal partners. Together, they unite communities and heritage assets along the 524-mile Corridor, including historic industrial sites, museums that interpret the industrial past, and community partners that provide critical educational programming. These efforts illustrate the important role that effective preservation, rehabilitation, and interpretation can play in highlighting the significance of former industrial sites and transforming former industrial communities.

Begun in 1817 and opened in its entirety in 1825, the Erie Canal system made the transportation of goods faster and cheaper. Industry grew along this early superhighway, creating the need for even more infrastructure. Expanding industry facilitated several episodes of canal expansion. Growing from its original 4-foot depth and 40-foot width to its currently maintained dimensions of 12 feet deep and 123 feet wide, these canals remain in service today. However, almost immediately after the canals opened, locomotives were introduced to the region. Beginning in the 1830s, rail lines were strategically built alongside portions of the canal system. By the 1870s, gross tonnage shipped on the canal system peaked. It was then that the first significant reduction in canal usage began and industrial investment shifted to new modes of transit and their associated facilities.

In the region encompassed by the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, what is sometimes referred to as “deindustrialization” may alternatively be characterized as “industrial migration” or “industrial shift.” Whether it is the shift in transportation modes from canal boat to locomotive in the mid-nineteenth century, or the twentieth-century geographical shift in industrialized manufacturing from the Northeast to the Midwest, the industrialized services did not outright disappear. Instead, many of the industrial processes simply evolved, were replaced by new industries, or relocated to other states, regions, or countries. What is certain is that when industry closes or relocates, what is often left in its wake is a forsaken landscape void of the lifeblood necessary to sustain formerly thriving communities. The broad-shouldered infrastructure that was once at the center of the industrialized landscape stands weakened and reduced to soulless remains. Historians and preservationists face questions such as “What do we want to conserve from our industrial heritage?” and “Why do we want to conserve it?” As the past haunts the future, we must address the fate of these abandoned landscapes, as well as the future of our industrial heritage.

Aerial view of the Matton Shipyard, circa 1949. Photo credit: Charles O’Malley Collection, New York State Museum.

The Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor works to do just that though its efforts to rehabilitate and interpret sites in the many formerly industrial communities along New York’s canals through public history and capital projects. Among the programs administered by the Erie Canalway are the Partner Program, the Matton Shipyard Adaptive Reuse Study, and the New York State Canalway multiuse and water trails. The Corridor’s over five hundred miles support a broad range of museums and cultural heritage sites. Some showcase important works of engineering, others include works of art or artifacts, and some highlight the value of the canal today. Through the Partner Program, over thirty designated partners share the powerful story of the canal’s role in shaping New York and the nation and are each responsible for delivering their unique perspective on the evolution of the canal system. They are supported in this work by the National Heritage Corridor, which provides technical assistance, coordinated tourism promotion, and facilitates networking among the sites.

At the Matton Shipyard in Cohoes, at the confluence of the Mohawk and the Hudson rivers, an adaptive reuse and feasibility project is one example of a community-specific interpretation and rehabilitation project within the Corridor. This locally owned and operated family-based shipbuilding facility demonstrates the role played by smaller industries in smaller cities along the Erie Canal. The historic Matton Shipyard is a rare surviving example of an early twentieth-century shipbuilding and repair facility. From 1916 to 1983, Matton workers built more than 340 tug boats, police boats, World War II submarine chasers, and other vessels. At its height, the shipyard employed more than three hundred workers. Today, the Canalway Heritage Corridor is working to convert the shipyard into a waterfront gateway for the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor by preserving existing buildings and the visual character of the site, promoting the site as a hub for recreational, educational, and cultural activities, opening access to the water for residents and visitors, and addressing long-term challenges, including flooding and economic sustainability. The hope is that Matton Shipyard will once again serve as a vibrant intersection of historical, cultural, educational, recreational, and commercial activities and bring new life to the surrounding communities.

Paddling Heritage Water Trails on the Oswego Canal, Lock O4, Minetto, New York. Photo credit: Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor.

Heritage trails are another effort to connect people with the history of particular areas or landscapes. Trails link recreational activities with opportunities to engage with New York’s industrial past. The New York State Canalway Water Trail, established by the New York State Canal Corporation and recognized in the New York Statewide Trails Plan, is designed to guide nonmotorized boaters through over 500 miles of operational canals. Once complete, cyclers will be able ride between Albany and Buffalo on the 365-mile Erie Canalway Trail. (The cycle trail is currently three-quarters finished.) Interpretive priorities include: the historic infrastructure of the canal system such as locks, dams, aqueducts, and guard gates; the historic communities that emerged alongside of the canal system; the industrial heritage founded upon the growth of the canals; and associated historic and cultural sites.

And what is the benefit of these programs? A recent 2015 economic impact study confirmed that the overall economic impact of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, one of the many agents actively addressing the challenge of revitalizing the communities along this former commercial and industrial highway by preserving and interpreting their industrial pasts, is $307.7 million annually. And that is just the economic benefit. Throughout the Corridor, industrial landscapes provide an ideal setting for engaging visitors in considering the history and the future of the rich industrial heritage across the canal system. By evaluating the needs of our industrial heritage, developing programming for preservation, interpretation, and education, and raising the resources to implement these programs, we can sustain these landscapes and communities for generations to come.

~ Brian Yates is the program manager at the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. He is a formally trained archaeologist and oversees several programs related to historic preservation, tourism and promotion, heritage development, and recreation.